Criminal Justice System In Pakistan: A Critical Analysis

Executive Summary

The Criminal Justice System in Pakistan comprises of five components i.e. the police, judiciary, prisons, prosecution, probation and parole. This study discusses and analyzes the efficiency level of these components by taking into account the work assigned and disposed of by every component of the criminal justice system during the year 2014. The scope of the study was limited to the four provinces namely Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. Data for cases registered by police, district and superior judiciary and prisons was obtained. A mix of primary and secondary data was used. It transpired that during the year 2014, a total of 612,835 cases were registered by police in four provinces of Pakistan out of which 26 percent were still pending with the police at the end of the year. Similarly cases taken up by the district courts at trial stage in the four provinces were 2,160,752 and 69.2 percent cases were disposed of during the year. The disposal rate of High Courts collectively was 53.9 percent and the disposal rate by the Supreme Court was less than fifty percent. The jails were found to be over crowded as they were overpopulated by 156 percent and majority included under-trial prisoners. Even though prosecution has been separated from police, it is still in infancy and no specialization or work load management system is in place. No credible data as to probation and parole was available, so it appeared to be a much neglected area. More or less the performance of criminal justice system is not at its optimal level in Pakistan and remedial measures like improvement and enhancement of physical infrastructures and capacity building of existing police, investigators, judges, prosecutors and jail staff is required along with focus on enhancing the existing strengths of investigators, judges, prosecutors and jails in order to improve the efficiency level and effectiveness of service delivery by the criminal justice system as a whole.

Glossary of Terms

FIR First Information Report

Challan Police report under section 173 of CrPC

CrPC Criminal Procedure Code 1898

PPC Pakistan Penal Code 1860

The criminal justice system in Pakistan is known to be faulty, exploitative and inequitable. These problems are most certainly some of the main causes behind high crime rates [1]. The civil and criminal justice system in Pakistan is confronted today with the serious crisis of abnormal delays. Delay in litigation of civil and criminal cases has become chronic and proverbial. The phenomenon is not restricted to Pakistan; it is rather historical and universal. It is inherent in every judicial system which meticulously guards against any injustice being done to an individual in a civil dispute or criminal prosecution. A paramount principle of the criminal justice system is that an accused is punished only after his or her guilt is proved beyond a shadow of doubt. Similarly, justice demands that in the trial of a civil case, the dispute must be decided strictly in accordance with the law and on the principles of equity, justice and fair-play. Such universally recognized and time-tested principles are also in accordance with the injunctions of Islam as the Holy Quran ordains that Muslims must eschew injustice, coercion and suppression.

The criminal justice system is defined as the set of agencies and processes established by governments to control crime and impose penalties on those who violate laws. This system has various components which have to work in harmony and support of each other in order to provide justice to not only to the victim but to the accused as well [2].

A good and reliable system of criminal justice not only caters to speedy remedy for the victims of crime but also safeguards and protects the legitimate rights of the accused. The system is based on fairness, equality, justice and fair-play for all – a system that deals with crime and criminals with the view to maintain peace and order in the society [3].

Criminal justice is the system of practices and institutions of the government directed at upholding social control, deterring and mitigating crime, or sanctioning those who violate laws with criminal penalties and rehabilitation efforts. Criminal justice system mainly consists of three parts:

(i) Police (law enforcement);

(ii) Courts (adjudication/trial);

(iii) Prisons (corrections/ probation and parole).

The criminal justice system of Pakistan has been inherited from the British. This system aims to reduce crime, bring more offenders to justice and raise public confidence that the system is fair and will deliver justice for law-abiding citizens.

The major and important deficiencies and weaknesses of the criminal justice system of Pakistan are accurate reporting of crime to the police, malpractices during litigation, delayed submission of challans to the courts by public prosecutors, lopsided and long duration of trials where the accused is considered to be the favourite child of the court, overcrowding of jails due to a large number of under-trial prisoners, underdeveloped system of parole and probation and capacity issues. These weaknesses, especially capacity issues, are not restricted to any one segment of the criminal justice system – all components including law enforcement, judiciary and corrections/prisons equally fall short.

The legal basis of the criminal justice system of Pakistan includes the Criminal Procedure Act of 1898 (popularly known as the CrPC) and Pakistan Penal Code 1860 which lay out the foundations, procedures and functions of all components of the system starting from reporting of the case to police, its trial by courts, appeals and correction at jails. However, even though amendments from time to time had been made in laws to cater for changing needs, Islamize laws and keep them up-to-date, the major shape is still the same. Unfortunately, Pakistan’s system has failed to achieve the wider objectives, that is why the Supreme Court observed that “…people are losing faith in the dispensation of criminal justice by ordinary criminal courts for the reason that they either acquit the accused persons on technical grounds or take a lenient view in awarding sentences [4].” This has resulted more often in people resorting to street justice and incidents involving lynching of criminals by public which have been reported by media a number of times [5].

Owing to the above shortcomings, the whole system of criminal justice is considered to be underperforming. In the past, several attempts were made at amending the legal framework to make the system efficient and improve its efficiency and effectiveness but those were largely in bits and pieces and were done half-heartedly, not yielding any positive results [6].

To critically analyze the functioning and interrelations of various components (police, courts, prisons, etc.) and their correlation with each other, the study will also focus on the weaknesses of the system and coordinated efforts to improve efficiency.

The main objective of the research is to analyze the flaws of the criminal justice system/criminal prosecution system in Pakistan and to find effective solutions to create an accessible, efficient and reliable justice system in Pakistan. Moreover, this study aims to analyze the issues concerning criminal prosecution, exploitation by law enforcement agencies and the vast problems existing in the lower courts of Pakistan. The study will be carried out with a number of general and specific objectives.

The specific objectives will be to:

(i) Critically analyze the working efficiency of each component in terms of work assigned and disposed of in a specific period of time;

(ii) Correlation of these components to one another in the efficient dispensation of justice.

The general objectives will be to:

(i) Identify weaknesses of the system;

(ii) Suggest measures for improving the overall efficiency of the criminal justice system.

The study will be limited to the aforementioned four provinces of Pakistan and major components of the criminal justice system i.e. police, judiciary and prisons. Data from calendar year 2014 will be used regarding all these components.

The nature of adversarial litigation is such that the parties themselves are responsible for preparation and presentation of their cases during interlocutory stages at trial. The cases are decided on legal and factual issues presented to the court while parties have complete control in the matter of factual investigation for that purpose. This necessarily means that the pace at which proceedings are pursued is largely dictated by the parties and the traditional role of the court is to adjudicate when called upon to do so [7].

An analytical study of the criminal justice system of Pakistan highlights its main lacunae and shortcomings and provides viable recommendations so that a fair trial could be ensured and radical changes for overhaul could be enforced [8]. Review of literature that has been carried includes a number of annual reports by various monitoring agencies along with research papers, journals, news items and books on the subject. The following literature was chiefly consulted:

SA Rehman Law Commission examined the causes of delays in civil and criminal litigation and recommended the appropriate amendments in relevant laws. The Commission, however, did not suggest any radical change in the existing judicial system [9].

Justice Hamood ur Rehman Law Reform Commission Report is a fairly comprehensive report on the subject of delays in civil and criminal litigation. It did not find any major fault with the existing legal system. The report listed recommendations under three categories namely legislative action, strict application of existing laws/rules and administrative action. It proposed for an increase in the number of judicial officers and allied infrastructure to reduce the time in disposal of cases [10].

Law Reform Committee Report recommendations were given with respect to increase the number of judges and provision of infrastructure to improve the work of investigation and prosecution officers [11].

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice’s Challenge of Crime in a Free Society (1967) suggested a systematic approach to criminal justice which improved coordination among law enforcement, courts and correction agencies [12].

Criminal justice system reflects a commitment by the society to prevent and control crime while dealing justly with those accused of violating criminal law [13].

It is a system of people, politics and procedures that interacts dynamically with agencies at all levels of government and with the interests and values of society at large [14].

A defense analyst has noted that, “The Police Order of 2002 increased senior police posts by 300 per cent. More than 15 percent of the police budget funds police administrators in the form of a long chain of supervisors above DSP (Deputy Superintendent Police) level [15].”

A mix of primary and secondary data has been used for the purpose of this study. Data related to the registration of cases by the police was collected from the respective Central Police Offices of the provinces and data about the disposal of criminal cases by district judiciary, high courts and supreme court was collected from Judicial Statistics of Pakistan for the year 2014.

Percentage analysis was used as the primary tool of data analysis. Percentage change – between the work assigned, disposed of and pending – has been the criterion to assess the output.

This paper consists of three main parts i.e. role of police, role of Judiciary and role of jails/prison departments in the criminal justice system. Furthermore the strong and weak areas will be identified accordingly with conclusion and recommendations.

Role of Police

The police has been entrusted under law to protect the life and property of citizens of the country. Criminal Procedure Code and Police Order 2002 provide necessary legal cover to the police to perform this function and bring criminals to book.

Police is the first and foremost component of the criminal justice system. Persons aggrieved of highhandedness approach the police for legal protection and redressal of grievances. This forms the basis of criminal action and the foundation of criminal justice system.

Registration of FIR: Criminal justice begins with a First Information Report (FIR) at a police station. It has been observed and usually complained about that police avoids registering the crime when reported and usually delays the registration of FIR. The delay in registration of FIR is due to a number of reasons, the foremost being non-willingness on the part of police as it will reflect badly on their performance. Other reasons may include extraneous pressures and corruption. The second stage is apprehension or arrest. The law requires any person taken into police custody to be presented before a court within 24 hours, with the magistrate then determining whether, prima facie, there are grounds for a case. This process, more often than not, is honoured. Magistrates commonly order a remand without even seeing the accused. Moreover, when judges do not remand the accused, the police often re-arrest him or her. By law, the accused cannot be in police custody for more than fourteen days, although courts typically grant extensions on the grounds that the police need more time to recover evidence. Meanwhile, the police are said to torture the accused to get a confession.

To provide relief to general public in the registration of FIRs and to counter delays, an amendment was made in CrPC and justices-of-peace were introduced by inserting a new section 22 A & B. Delay in registration of FIRs, non-registration of FIRs and the powers of justice-of-peace are dealt with under the said section.

However, the police still have to register the FIR as justice-of-peace can only pass an administrative order to the concerned Station House Officer (SHO) for registration of FIR. No separate register for registration of such FIRs has been prescribed. If the same is prescribed, a problem will arise as to who would carry out the investigation and submit challan to the court, the police or the justice-of-peace?

It has also been observed that after the introduction of section 22A and B, the number of false FIRs has increased as the FIRs which were usually not registered by the local police on suspicion of being false and fabricated, are now ordered under 22A of CrPC by the concerned justice-of-peace directing local police to register the same. This has largely been misused.

Investigation: This is the second most important function performed by the police. After the registration of FIR the matter is assigned to a police officer for investigation. Investigation is carried out under the procedure given in CrPC as well as the guidelines given in Chapter 25 of the Police Rules 1934. Investigation is the process of collection of evidence to establish the commission of any offence and the roles played by individuals in commission of those offences. Once evidence is collected and grounds of involvement or innocence of the accused are established, the investigating officer (IO) prepares challan for submission to the court. CrPC provides powers to the investigating officer to acquit any accused against whom no evidence of involvement is found under section 169 but this practice is usually disliked by the courts and they insist that the police should challan them under Column No.2 of the challan. This causes delay in justice and puts the falsely implicated persons under undue torture and delay in getting relief and being discharged. All accused against whom no evidence is received should be released by the police.

Quality of investigation by police and timely completion of investigation is of vital importance for the dispensation of justice and effective operation of the criminal justice system. Under the law, investigation officer is bound to submit challan in 17 days before the court. As it is practically not possible to collect all of the evidence in such short time, interim challans are submitted in this period and investigations at times take months to complete.

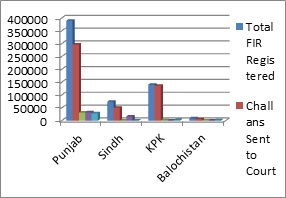

FIGURE I – Police Work Load 2014

Figure I depicts the registration of FIRs by various provinces and the challans submitted. It is clear that the maximum number of FIRs was registered in Punjab whereas Khyber Pakhtunkhwa police was able to send the maximum number of registered cases to court.

During the year 2014, a total of 612,385 FIRs were registered by the four provinces’ police. This is the number of crimes that has been registered by police. The actual number of crimes reported to the police is higher than this as there is a tendency that not all of the crimes reported to the police get registered. Similarly there are also some instances where crimes are not reported to police at all.

Police submitted almost 80% of the cases to court after investigation and at the end of the year only 27% of the cases were pending for investigation with the police. The detailed breakup province-wise is given in Figure I.

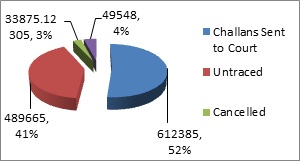

It is evident from the data of the year 2014 that a total of 612385 FIRs were registered by the police all over Pakistan out of which almost 3% were cancelled for being false or lacking evidence and 52% were challaned and sent to courts. The cases under investigation come to around 4%. We can safely infer from this data that police has completed almost 97% of the work assigned during this period. This analysis is purely on the quantity of work disposed of and not on the quality of investigations.

FIGURE II: Annual Police Workload Country-Wide

Source: Central Police Offices Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan.

Reforms in Police System: Much has been talked about reforms in the police system but all of these are cosmetic. No real focus has been made on the root causes of the problems. Mere amendment in laws will not yield the desired results.

Police powers under s.54 and 169 CrPC are largely criticized by the judiciary for their misuse by the police. Law has given powers to police officers which they should exercise in a transparent manner and in the interests of justice. An SHO has been been given powers of bail but these are not exercised in ordinary circumstances. The application of law and the use of powers of bail by an SHO should be without fear or favor as it will be the first level of redressal or relief to any accused against whom a false FIR has been registered. It should rather be made mandatory that any person against whom an FIR has been registered should be accorded the facility of bail as soon as he or she reports at the concerned police station while investigation on him or her should be conducted in the same manner as of any other person on bail before arrest.

Police stations are also inadequately equipped, sometimes even lacking proper premises. Police budgets do not cover individual stations. Instead, allocations for arms and ammunition, transport, maintenance, stationery and other necessary items are centralized in provincial police budgets and then distributed to stations. Many stations do not have their basic requirements met and their monthly expenditures outpace their allocations. Most stations are self-financed to a significant extent. For example, police may pay for their own stationery and maintenance of vehicles, including petrol. The SHO becomes beholden to others because he or she is relying on them to provide the station with vehicles, equipment, and so on, to be able to carry out their jobs. The SHO is similarly beholden to superiors who often interfere in the business of police stations on behalf of outsiders, including intelligence officials. The Police Order 2002 made the force even more top-heavy, further weakening police stations’ operational independence and efficacy.

Role of Judiciary

Pakistan’s courts and prisons are overburdened. At the start of 2014, excluding those before special courts and administrative tribunals, there were more than 138,296 cases pending in the superior courts, including the Supreme Court and provincial High Courts, and more than 2.6 million with the subordinate judiciary. Police, lawyers and judges agree that the number of courts needs to be doubled at a minimum [16]. Staffing those courts will be an even more crucial task. Around 900 magistrates with civil and criminal jurisdiction for a population of roughly 160 million handle around 75 per cent of all criminal cases [17]. While there have been some improvements in recruitment and salaries, with the Punjab government for example tripling judicial officers’ salaries, the benefits are not visible yet and trained judges are scarce.

There is the Supreme Court with its principal seat in Islamabad, High courts in all provinces and sessions courts in each district of the province headed by sessions judges who deal with criminal cases. Then there are further subordinate courts of additional sessions judges and judicial magistrates.

Criminal cases punishable with death and life imprisonment as well as cases arising out of the enforcement of laws relating to Hudood are tried by sessions judges. Offences not punishable with death or life imprisonment are tried by judicial magistrates.

An appeal against the sentence passed by a sessions judge lies to the High Court and against the sentence passed by a judicial magistrate, a special judicial magistrate or a special magistrate to the sessions judge if the term of sentence is up to four years, otherwise to the High Court.

Trial Stage: Trials are carried out at district levels where subordinate judiciary undertakes the same. There is a rampant delay in deciding cases and it is owing to this delay in framing charges, recording evidence, examining witnesses and other delaying tactics used by lawyers for ulterior motives, that derail due process for the benefit of the accused. There is no fixed time-frame for the completion of trial in criminal cases.

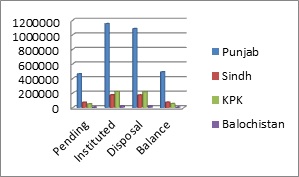

FIGURE III: Annual District Judiciary Work Load Province Wise Year 2014

Source: Judicial Statistics of Pakistan 2014

Province wise breakup of disposal of work by the district judiciary is given in Figure III.

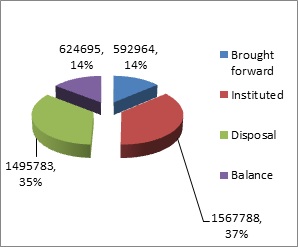

FIGURE IV: Annual District Judiciary Work Load Year 2014

Source: Judicial Statistics of Pakistan 2014

The highest pendency brought forward was 29% in the district courts of Sindh. The highest disposal of cases was 79.9% carried out by the district courts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa followed by 79.8% by the district courts of Balochistan. The least disposal of cases was by the district judiciary of Punjab.

A total of 2,160,752 cases were placed before the trial courts during the year 2014. Out of these 592,964 had been brought forward from the previous year 2013. The total cases disposed of during the year were 1,495,783 which were 35% of the total cases for the year 2014. The cases pending were about 14% of the total. It is pertinent to mention that a bulk of cases, that is 37% is instituted during the year. The balance brought forward and left at the end of the year is almost same which shows that the level of pendency is not decreasing rather it is increasing at a constant rate. This is alarming and needs special attention and efforts to tackle otherwise it will keep on increasing and will defeat the actual rate of disposal severely. This also highlights that cases are delayed for over one year. The reason as highlighted earlier is the huge burden of cases per judge.

High Courts: There are four High Courts in the country with principal seats in all the provincial headquarters. The cases instituted by the High Courts and their disposal are shown in FIGURE V below.

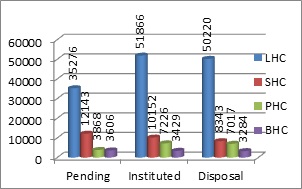

FIGURE V: Annual Workload of High Courts Province-Wise Year 2014

Source: Judicial Statistics of Pakistan 2014

The highest pendency brought forward from the previous year was in Sindh High Court. Peshawar High court was the most efficient in disposal of assigned work as it had disposed off almost 63% of the cases followed by Lahore High court with 59.5% disposal rate. The minimum disposal of cases during the year was of Sindh High Court as reflected in the figure.

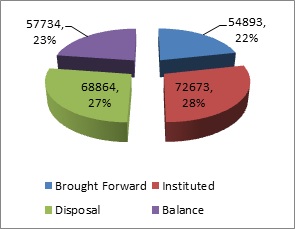

The pie-chart shows the collective disposal rate of all High Courts of the four provinces, which comes to 27% of the cases (instituted and brought forward) at the beginning of year 2014. 22% pendency was brought forward and at the end of year 2014, it rose to 23%. This situation is not very satisfactory.

FIGURE VI: Annual Workload of High Courts Case-Wise Year 2014

Source: Judicial Statistics of Pakistan 2014

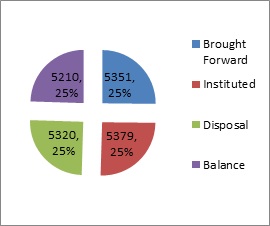

Supreme Court: The delay at Supreme Court level is not only phenomenal but also causing an increasing backlog. There is a proverb that “justice delayed is justice denied”. In a recent case of Khawaja Mazhar Inayat, the accused who was convicted in a murder case in 1997 by the lower judiciary, was exonerated of the charges being false by the Supreme Court after almost 20 years of that conviction. It transpired later that the said accused had died of a cardiac arrest two years earlier (in 2014) in District Jail Jhelum.

A total of 10,730 criminal cases were placed before the Supreme Court of Pakistan during the year 2014. Out of these 5,379 were instituted during the year 2014. 5,320 cases were disposed off during the year 2014, which comes to around 49.5% and the balance left behind is about 5210 cases, that is almost 48.55%. It is pertinent to note that the pendency brought forward was 49.8%. Accordingly, the pendency brought forward and disposal is almost at the same rate.

FIGURE VII: Annual Work Load of Supreme Court of Pakistan in the year 2014

Source: Judicial Statistics of Pakistan 2014

Figure VII clearly shows that the pendency brought forward is almost equal to the disposal. The remaining balance is almost equal to what the Supreme Court started with at the beginning of the year. There is a need for the ratio of disposal of cases by Supreme Court to be higher than the cases instituted or pending, only that way it will be able to clear the pendency otherwise the level of pendency will remain the same.

Prosecutors: The decision to take a case to trial ultimately rests with the prosecutor. While the courts, prisons and police represent the public face of the justice system, the relatively small prosecution services have lesser needs for elaborate infrastructure than the other three. Nevertheless, they form the core of the criminal justice system and their effectiveness determines the effectiveness of the system. Until 2002, prosecution services were part of the police. Each provincial force maintained its own prosecution wing, comprising of law graduates of the rank of sub-inspector, inspector or deputy superintendent. The Police Order 2002 separated prosecution services from police, bringing them under the Law Department. Between 2003 and 2006, all four provinces passed a Criminal Prosecution Service Act to establish “an independent, effective and efficient service for prosecution of criminal cases, for better coordination in the criminal justice system of the province” [18]. A Prosecutor General heads each provincial service, appointed by the provincial government. Below him or her are Additional Prosecutors General, Deputy Prosecutors General and Assistant Prosecutors General – there are District Public Prosecutors, Deputy District Public Prosecutors and Assistant District Public Prosecutors at the district level. Separating police and prosecution was overdue, but the newly established service faces major difficulties. Inducting recruits with criminal law expertise remains a major challenge, particularly as the prosecution services have yet to develop their institutional identity. “Prosecutors with only three or four years of experience are serving as District Attorneys or Assistant District Attorneys,” said a former Inspector General (IG) Punjab [19]. A former Supreme Court Chief Justice added that, “To separate prosecution from the police, you need to properly fund it and equip it with a competent lawyer. That has not happened.”

Since no data was available as to how much work had been assigned per year to prosecutors, parole and probation officers, no analysis as to their work assigned and disposed of in a year was carried out.

Role of Prisons

Prisons are overcrowded, with prisoners on trial accounting for more than 80 percent of the prison population. Only 27,000 of the country’s roughly 81,000 prisoners have been convicted. In early 2010, a major prison in Lahore, with a capacity for 1,050 held 4,651 prisoners. There has been some improvement in recent years. In August 2008, for instance, Sindh’s prison population was over 20,000; by September 2010 Sindh’s prisons held 18,234 prisoners but still significantly above the prison capacity of 9,541 and with only 2,641 convicts [20]. Prison resources, which would be inadequate even for a smaller prison population, are overstretched. A Sindh provincial minister told the Sindh Assembly that the government had only 155 vans to bring more than 13,000 prisoners to courts and that is why prisoners are seldom transported to courts on the date of their hearing. “It seems to take more time to bring a person to court than to actually dispose of the case,” said a former Sindh Advocate General. Conditions are abysmal and prisoners’ rights are regularly violated, for example, remand prisoners are assigned to labourious work in contravention of the law.

This huge prison population also poses serious security implications – law enforcement officials refer to prisons as the ‘think-tanks’ of militant groups, where networks are established and operations are planned, facilitated by the availability of mobile phones and a generally permissive environment. Prisons have thus become major venues of jihadi recruitment and activity.

There have been a few sustained efforts to address overcrowding and the conditions of prisoners under-trial, and to even implement existing codes and procedures. In 1972, Pakistan’s first elected government led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s People’s Party, introduced a reforms-package aimed at improving delivery of justice and provision of relief for prisoners through bail. According to Section 426 (I-A) of the CrPC:

An appellate court shall, unless for reasons to be recorded in writing it otherwise directs, order a convicted person to be released on bail who has been sentenced

a) to imprisonment for a period not exceeding three years and whose appeal has not been decided within a period of six months of conviction;

b) to imprisonment for a period exceeding three years but not exceeding seven years and whose appeal has not been decided within a period of one year of conviction.

The prisons are overcrowded, most of them with prisoners under-trial. The total capacity of all prisons in four provinces is 50,709. However, prisoners housed at present in these prisons are 80,089 which is almost 158 percent of the existing capacity. The highest percentage is that of under-trial prisoners, which accounts for 149 percent.

Table I: BUILT CAPACITY AND CURRENT POPULATION OF PRISONS IN PAKISTAN

| Capacity of Jails | Under-Trial | % | Convicted | % | Condemned | % | Total | |

| Punjab | 27824 | 31119 | 111.84 | 12680 | 45.57 | 5153 | 18.51 | 49889 |

| Sindh | 12416 | 36212 | 291.65 | 4541 | 36.57 | 460 | 0.53 | 19604 |

| KP | 7996 | 7100 | 88.79 | 2940 | 36.76 | 196 | 2.45 | 8113 |

| Balochistan | 2473 | 1600 | 64.69 | 833 | 33.68 | 50 | 2.02 | 2483 |

| Total | 50709 | 76031 | 149.93 | 20994 | 41.40 | 5859 | 11.55 | 80089 |

Source: http://sindh.gov.pk/dpt/sindh_prsions/All%20PDF/Population%20Statement.pdf

Probation: Probation is the judicial action that allows the offender to remain in the community, subject to conditions imposed by court order, under the supervision of a probation officer. It enables the offender to continue working while avoiding the pains of imprisonment. In developed countries, social services are provided to help the offender adjust in the community – counselling, assistance from social workers and group treatments as well as the use of community resources to obtain employment, welfare and housing, etc. are offered to the offender while on probation. In some countries community-based correctional centers have been established for first-time offenders where they live while keeping their jobs or obtaining education [21].

Parole: The parole system in our country is not much established. In other developed countries the convicted are selected for early release on the condition that they obey a set of restrictive behavioral rules under the supervision of a parole officer. The main purpose of early release is to help the ex-inmate bridge the gap between institutional confinement and positive adjustment within the community [22].

After their release offenders are supervised by parole authorities who also help them find jobs, deal with family and social difficulties and gain treatment for emotional or substance abuse problems. If the offender violates the conditions of community supervision, parole may be revoked and that person may be sent back to jail for completion of his or her remaining term [23]. A system of remissions is in practice whereby a remission/reduction in sentence is granted keeping in view the good behavior of the convict and the nature of crime committed by him or her.

The criminal justice system of Pakistan is not performing according to the wishes and expectations of the public and the values of society. Dispensation of justice gets delayed in the process of registration of FIRs by police, poor quality of investigations, long duration of trials, poor prosecution, overcrowded jails, rampant corruption among all departments dispensing justice, lack of infrastructure facilities for police, courts, prosecutors and jails to adequately and properly meet workload and the absence of a conducive work environment. This is resulting in constant increase in pendency and poor disposal ratio.

The following recommendations are proposed for the improvement of criminal justice system:

1. The Criminal Procedure Code needs to be redrafted and amended with specific reference to police responsibilities and powers for:

a. Registration of FIR Section 154. Redesigning business procedure for simplified registration of FIR.

b. Police powers to release accused during course of investigation if no evidence found under Section 169.

c. Repealing section 22A and B relating to justice-of-peace for the purposes of registration of FIR.

d. Redesigning the form for submission of challan under s.173 and the time-frame for submission of challan.

e. Fixation of time-frame to conclude trial by the courts once challan is submitted by police.

2. Amendments in Qanoon-e-Shahadat Ordinance should be made by:

a. Including confession before a police officer as admissible evidence.

b. Giving more weightage to circumstantial evidence as compared to eye-witness account.

3. All offences to be made cognizable and the distinction of cognizable and non-cognizable to be abolished.

4. Registering FIR by police and amending law to provide for FIR should not be the basis for the arrest of any accused. Arrest can be made based on warrants duly issued by the court after examination of evidence produced by the police.

5. The importance of police stations in maintaining computerized records of all FIRs cannot be over-emphasized. It is necessary to devise a process for citizens to check the status of their FIRs and complain to the proper authority in case of neglect. Online computerization of the registration of FIRs, criminal investigation and court proceedings, along with jail authorities maintaining proper coordination among all components of the criminal justice system will improve transparency and reduce delays.

6. A monthly progress review should be made on district as well as provincial level by the Deputy Commissioners/ DCOs and Chief Secretary to assess the working performance of all the components of criminal justice system.

7. All provincial High Courts and district courts be made accountable for their performance to the government, as there is often a gross misuse of the term ‘independence of judiciary’ by the judiciary itself to ridicule other government institutions, for personal gains and satisfaction of egos. Since judiciary is being financed by taxpayers’ money, they should also be held accountable to the public and the state, through an independent system as well as through internal checks.

8. Infrastructure development is necessary at police station level as well as trial-court level.

9. The cost of investigations should be realistically calculated and budgeted accordingly.

10. Production of witnesses from both prosecution and defense sides should be ensured and the process of serving should be updated electronically by developing a mechanism to record their evidence in one sitting.

11. Ongoing empowerment and capacity building of police, judiciary and jail staff for timely and efficient dispensation of justice and quick disposal of cases must be ensured.

12. Human resources must be enhanced i.e. the number of investigation officers and judicial officers, in order to conduct trials more efficiently and reduce pendency of cases under trial.

13. Video-conferencing should be encouraged to save the time and cost of travel otherwise carried out to physically produce the accused before court from the police station or jail.

14. Establishment of separate prisons for under-trial and convicted prisoners and a more organized system of probation and parole to reduce the burden on existing jails should be ensured.

———

References and Bibliography

[1] Hamza, Hameed, and Kamil, Jamshed, “A study of criminal law & prosecution system in Pakistan 2013”

[2] Munir, A, Mughal, “Law of investigation into cognizable case”.2009

[3] Munir, A, Mughal, “Law of investigation into cognizable case”.2009

[4] Ali, Sardar Hamza. “An Analytical Study of Criminal Justice System of Pakistan (with special reference to the province of punjab).” Journbal of Political Studies, Vol.22, Issue-1, 2015.

[5] www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2016/07/17/city/karachi/alleged-mugger-lynched-in-city/

[6] Jamshed, Hamza Hameed & Kamil. A study of Criminal Law & Prosecution System in Pakistan. Manzil Pakistan, 2013.

[7] Karim, Justice (R) Fazal. Access to Justice in Pakistan. 2003.

[8] Ali, Sardar Hamza. “An Analytical Study of Criminal Justice System of Pakistan (with special reference to the province of punjab).” Journbal of Political Studies, Vol.22, Issue-1, 2015.

[9] Rehman, S A. “Law Commission Report.” 1958.

[10] Hamood ur Rehman, “Law Reform Commission Report.” 1996.

[11] Law reform committee report 2015

[12] President’s Commission on law enforcement and Administration of Justice (1967)

[13] Smith, Christopher E. American Crimnal Justice System . 2013.

[14] Smith, George F Cole and Christopher E. The American system of Criminal Justice . Belmontn CA, 1998.

[15] International Crisis Group working to prevent conflict world. Reforming Pakistan’s Criminal Justice System. Asia Report No 196 , 2010.

[16] International Crisis Group working to prevent conflict world. Reforming Pakistan’s Criminal Justice System. Asia Report No 196 , 2010.

[17] Judicial statistics of Pakistan 2014

[18] International Crisis Group working to prevent conflict world. Reforming Pakistan’s Criminal Justice System. Asia Report No 196 , 2010.

[19] International Crisis Group working to prevent conflict world. Reforming Pakistan’s Criminal Justice System. Asia Report No 196 , 2010.

[20] International Crisis Group working to prevent conflict world. Reforming Pakistan’s Criminal Justice System. Asia Report No 196 , 2010.

[21] https://pakistanilaws.wordpress.com/2012/05/03/criminal-justice-system-in-pakistan-2/

[22] ibid

[23] The Good Conduct Prisoners Probational Release Act 1926

Ali, Ashraf. Probation and Parole System A case Study of Pakistan. a, 2013.

Ali, Ashraf. Probation and Parole System: A Case Study of Pakistan.

Mardan: Abdul Wali Khan University, 2013.

Ali, Sardar Hamza. “An Analytical Study of Criminal Justice System of Pakistan (with special reference to the province of Punjab).” Journal of Political Studies, Vol.22, Issue-1, 2015.

Jamshed, Hamza Hameed & Kamil. A study of Criminal Law & Prosecution System in Pakistan. Manzil Pakistan, 2013.

Karim, Justice (R) Fazal. Access to Justice in Pakistan. 2003.

Mughal, Dr Munir A. “Law of investigation into cognizable case.” Punjab University Law College, 2009.

Pakistan, Law & Justice Commission of. Judicial Statistics of Pakistan, Annual Report 2014. Annual Report, Islamabad: Law & Justice Commission of Pakistan, 2014.

Rehman, S A. “Law Commission Report” 1958.

Smith, Christopher E. American Crimnal Justice System 2013.

Smith, George F Cole and Christopher E. The American system of Criminal Justice . Belmontn CA, 1998.

“The Good Conduct Prisoners Probation Release Act 1926” n.d.

“The Probation of Offenders ordinance 1960” n.d.

International Crisis Group working to prevent conflict world.

Reforming Pakistan’s Criminal Justice System. Asia Report No 196, 2010.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which he might be associated.