INTRODUCTION

Globally, the spread of COVID-19 is causing shutdowns and delays. With several countries and nearly all Pakistani provinces under virtual lockdown, businesses may be concerned about COVID-19’s impact on their commercial contracts. Contracts generally create obligations that must be performed. But in times of COVID-19, contract parties may find it hard to perform their obligations.

Contracts related to the shipping, transportation, construction, tourism, textiles, chemicals, automobiles, energy, as well as those in other industrial sectors may be impacted. Certain regular rent contracts may also be adversely affected.[1] Some international law firms are also raising concerns about the performance of “Belt and Road” projects.[2] In the midst of general uncertainty about COVID-19’s impact on business, it is important to examine options available to contract parties.

Generally, parties concerned about affected contracts should develop coherent strategies for risk management with their legal teams. Specifically, they may want to explore whether they can rely on a force majeure clause or impossibility and frustration. In doing so, they should account for dispute resolution considerations. For current and future contractual negotiations, they may wish to draft specific clauses responding to COVID-19 disruptions. Separately, they may analyze insurance implications for their business interruptions. Insurance matters are beyond the scope of this note. The rest of this primer explores issues relevant to contract parties.

Has COVID-19 Impacted Your Contract?

Parties should determine whether their contracts are adversely affected by COVID-19 and associated lockdowns. Specifically, they should examine whether performance has become (i) harder and more expensive or (ii) impossible or unlawful to perform because of COVID-19 or associated curfews and lockdowns.

Contract law generally helps with (ii). Parties may rely on contractual force majeure (supervening force) clauses to the extent applicable. These clauses shield parties from liability for non-performance. They typically suspend parties’ obligation to perform for some time. In some cases, they may also provide options for terminating contracts. For contracts governed under Pakistani law, parties whose contracts have no force majeure clauses or inadequate ones may also rely on Section 56 impossibility (and frustration) under Pakistan’s Contract Act of 1872.[3]

For (i), broader options available to parties may be more limited. Some contracts may have price renegotiation, time extension or other change in circumstances clauses. These clauses are relatively rare in common law jurisdictions since agreements to agree are generally frowned upon.[4] Where they exist, parties may rely on them to the extent applicable.

(A) Can You Rely on a Force Majeure Clause?

Parties should carefully consider whether they have, at minimum, a (i) a force majeure event as defined by the force majeure clause in their contract and (ii) causation, that is, a causal link between the force majeure event and their inability to perform. Force majeure clauses may require that parties mitigate the impact of the force majeure event to the degree possible.

Whether COVID-19 counts as a force majeure event depends on the drafting of the force majeure clause in question. Some contracts exhaustively list out force majeure events. Other contracts are non-exhaustive. Generally, some reference to an epidemic, pandemic, disease, or quarantine, would improve a party’s prospects of relying on a force majeure clause. More broadly, reference to general terms such as “act of God” or “emergency” in force majeure clauses may also help to some degree, depending on context. For instance, COVID-19 would probably count as an “act of God,” but government measures causing lockdowns or curfews may not.[5]

In performing their assessment, parties should consider procedural requirements associated with their force majeure clause. Many force majeure clauses have a notice requirement. Parties relying on force majeure clauses should comply with notice requirements.

Parties should also consider whether their force majeure clause requires resumption of contractual obligations once the force majeure event ends.[6] Some clauses also provide parties the chance to renegotiate some terms or the option to terminate the contract if the force majeure event persists for a certain period.[7] Accordingly, depending on the language of their contracts, parties should plan to resume their contractual obligations or prepare for their contract’s termination.

(B) What is the Governing Law of Your Contract?

Many commercial contracts have a governing law clause that determines which country or state’s law applies. It is uncommon for commercial parties to omit such clauses. Where such clauses are omitted, complex rules for determining governing law apply.[8]

Contract parties tend to prefer consistency between their governing law and jurisdiction clauses. So where they want English Courts to resolve disputes under their jurisdiction clauses, they also choose English law as the governing law. Arbitration clauses are special kinds of jurisdiction clauses.[9] Many Pakistani business parties may be engaged in contracts governed under the laws of New York State or England and Wales. Determining governing law helps establish redress options for COVID-19 affected contracts, particularly where those contracts lack force majeure clauses and parties wish to rely on statutory law or common law principles.

(C) Should You Rely On Impossibility or Frustration?

For contracts governed by Pakistani law, Section 56 of Pakistan’s Contract Act of 1872 operates to render impossible contracts void. Where contracts lack force majeure clauses or where those clauses do not cover diseases, epidemics, pandemics or related government measures, Section 56 impossibility or frustration may help.

But what is impossibility? Our law generally operates within the broader context of the common law’s doctrine on frustration. In their assessment of impossibility under Section 56, our courts may construe impossibility not as physical impossibility, but as impracticability.[10] Frustration features as a component within the larger doctrine of supervening impossibility.[11] English case-law on frustration is persuasive, but not binding. Unlike force majeure clauses that parties may invoke to temporarily excuse performance, Section 56 operates to make contracts void. Under Section 56, an agreement to do an impossible act is void.[12] Further, a contract to do an act that becomes impossible or unlawful after parties enter into the contract is also void.[13]

To illustrate: In a case concerning the transportation of oilseeds, a defendant had contracted to deliver oilseeds to the plaintiff.[14] But the defendant was unable to deliver oilseeds because a District Magistrate in Tharparkar passed an order, under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of 1898, outlawing the transportation of oilseeds out of Tharparkar for one month. Pakistan’s Supreme Court found that the defendant was no longer obliged to deliver the oilseeds.[15] It was impossible and unlawful for the defendant to perform that contract per Section 56. Accordingly, the plaintiff received no compensatory damages for the defendant’s failure to deliver oilseeds.[16] In the context of COVID-19, similar orders may hinder the performance of several Pakistani contracts. Would impacted contracts be considered void under Section 56? Possibly. Parties and their legal teams would have to perform a case-by-case analysis.

For performance that has become harder or more expensive, parties may find it difficult to show impossibility or frustration under Section 56. We assume that contract parties take general risks associated with changes in price and market conditions so impossibility and frustration may also be of limited general help. For instance, in Kadir Bakhsh & Sons v. Province of Sindh, a Sindh High Court case concerning a lease of toll tax collection, the plaintiff, a lessee, claimed that his lease contract with the defendant was partially frustrated.[17] The plaintiff collected toll tax between Karachi and Hyderabad on lease from the defendant. For some time, traffic was suspended on that route because of civil unrest. The plaintiff sued for the partial frustration of the lease contract, demanding a refund of lease money for that period. The court held that there was no frustration since their lease contract specifically anticipated fluctuations in traffic, stating that frustration applies only when “something which is unanticipated happens.”[18] What about toll tax collection leases in times of COVID-19, when highway traffic is minimal? Courts’ findings would depend on the drafting of the contracts and construction of any relevant government orders, among other factors.

(E) Incorrectly Claiming Force Majeure or Impossibility

Claiming force majeure incorrectly or failing in a suit for impossibility carries its own set of risks. Incorrectly invoking a force majeure clause and not performing contractual obligations may afford a counterparty the ability to successfully claim for breach and damages. Doing so may also carry reputational costs and damage commercial relationships. For regulated sectors, force majeure declarations or their absence may impact regulators’ risk assessments.[19]

Parties with unfavorable contracts may use COVID-19 as an excuse to avoid their obligations. Reputational and legal costs associated with frivolous or bad faith use of force majeure or Section 56 may deter them. Nonetheless, if parties fear unscrupulous behavior from counterparties in this context, they should seek specific legal advice.

(F) Potential Remedies

Force majeure clauses typically allow suspension of contractual obligations for the duration of the force majeure event. Some such clauses may also provide for the discharge or termination of contracts under certain conditions.

Where Section 56 impossibility or frustration is engaged, Section 65 of Pakistan’s Contract Act of 1872 governs relief. Where performance becomes impossible, parties must restore or compensate for any advantage received under the contract.[20] Depending on the construction of the contract, parties may have to return any advance sum received, but not a security deposit which parties were meant to forfeit.[21] Interest may be payable on money returned.[22] The application of Section 65 restitution is context sensitive.

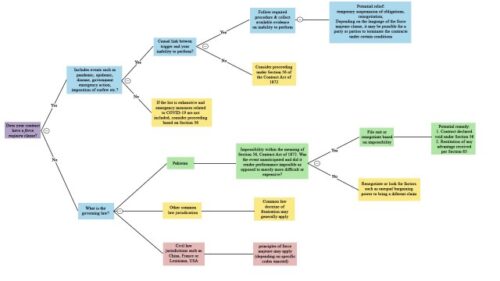

Figure 1 provides a broad overview of Pakistani parties’ approach to COVID-19 impacted contracts.

Fig 1. Overview of general options for COVID-19 impacted contracts. Graphical Editing Credit: Ali Ahmed, MBA 2020, IBA Karachi

(G) Considerations for International Contracts

Separately, Pakistani businesses should be alert to the possibility of North American, European, Middle Eastern, Chinese, South East Asian or other contract counterparties claiming force majeure. Since many businesses in China closed before their counterparts in Europe and North America, available literature focuses on the effects of that closure. Although China has returned to business, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT) has issued force majeure certificates to many Chinese companies. By early March, CCPIT had issued 4811 force majeure certificates to Chinese companies in over 30 sectors, covering contracts worth over US $ 53.79 billion.[23] The precise effect of these certificates is moot. For contracts governed under Chinese law and resolved before courts in China, such certificates may prove helpful, but parties relying on them will also have to satisfy other force majeure requirements including those related to notice.[24]

Internationally, the impact of these certificates may be more limited.[25] Many international business contracts involving Chinese and other foreign contract parties are governed by English law.[26] For force majeure claims determined according to English law, parties will have to satisfy usual requirements related to triggering events and causality.[27]

In some sectors, the effect of force majeure declarations is already apparent. In the liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation that operates several LNG import terminals in China, has invoked force majeure clauses in multiple long-term contracts with overseas suppliers.[28] With lockdowns taking place globally, we may witness disruptions in production, delivery and payment for this sector as well as others. Pakistani companies may also either declare force majeure or suffer its consequences. Accordingly, Pakistani contract parties, especially those involved in international business transactions, should assess and plan for contingencies related to force majeure clauses.

(H) Renegotiation and Dispute Resolution

For contracts that have force majeure clauses, a party’s refusal to accept another party’s invocation of a force majeure clause would usually be the formal starting point for dispute resolution. Initially, parties should seek to negotiate their dispute. Failing that, they should attempt mediation or arbitration before proceeding to court. Depending on the contract, arbitration or mediation may be required in some cases.

Since Pakistani courts are closed for non-essential cases and are expected to have a backlog on reopening, parties should first seek to amicably resolve disputes through alternative dispute resolution methods to save time and costs.

Independent of a dispute, parties should attempt to communicate with their counter-parties if they anticipate difficulties in performing their contractual obligations. Some force majeure clauses may open doors for renegotiation related to the resumption of contractual obligations. If a contract leaves that door open, parties may want to attempt good faith renegotiations.

(I) Negotiating New Contracts in Times of COVID-19

Parties entering into new contracts at this time may find it harder to rely on statutory impossibility and frustration for upcoming COVID-19 related disruptions. Section 56 generally applies to unanticipated events. For parties entering into contracts over the coming weeks and months, COVID-19 disruptions may no longer be unanticipated or unforeseen.

Similarly, while negotiating force majeure clauses for upcoming contracts, parties should remember that a clause requiring an ‘unforeseen’ force majeure event may not help with upcoming COVID-19 disruptions. Since parties already know about COVID-19 and its effects on business, continued COVID-19 disruptions, particularly those related to resumption of lockdown measures already in force, may not be entirely ‘unforeseen.’

While it is difficult to make general force majeure clause drafting recommendations, parties should consider some risk reduction and allocation options. Current data suggests that only 14 percent of international commercial contracts involving a Chinese commercial party have force majeure definitions that include pandemic, flu, epidemic, plagues, diseases or emergencies. [29] At minimum, those engaging in negotiations now should include those terms in their force majeure clauses.

Parties should also consider including a few clauses to carefully assume and allocate risk for continued and future disruptions. Their options include using flexible switch-on, switch-off clauses that switch on when COVID-19 conditions improve, but switch off when COVID-19 resurges.[30]. Mainly, parties should expressly allocate risks for closures and delays. Agreeing on obligations and loss allocation in advance can help prevent costly dispute resolution in the future.[31]

CONCLUSION

Commenting on implied terms, uncertain events and frustration of contracts, Lord Sands observed,

“A tiger has escaped from a travelling menagerie. The milkgirl fails to deliver the milk. Possibly the milkman may be exonerated from any breach of contract; but, even so, it would seem hardly reasonable to base that exoneration on the ground that ‘tiger days excepted’ must be held as if written into the milk contract.”[32]

COVID-19 is causing far more damage than Lord Sands’ tiger on the loose. It has introduced general commercial uncertainty. Contract law is not exempt from that uncertainty.

Upcoming challenges for courts and dispute resolution bodies will involve determining the balance between requiring parties to perform their contractual obligations and allowing them to avoid those obligations. In the context of frustration and impossibility, the age-old contest between pacta sunct savanda (promises must be kept) and non haec in foedera veni (it was not this that I promised to do) is likely to persist.

Parties should review their existing contracts, evaluate their options and seek specialized legal advice. They should also factor constraints related to COVID-19 in their current and future contract negotiations.

References

[1] April F. Condon et al, COVID-19 Impact on Commercial Real Estate, Day Pitney Advisory (March 26, 2020), https://www.daypitney.com/insights/publications/2020/03/26-covid19-impact-on-commercial-real-estate

[2]Mun Yeow and Jon Howes, COVID-19 Projects & Construction: Belt & Road Legal Issues, Clyde & Co (Feb. 2020), https://www.clydeco.com/insight/article/the-legal-ramifications-of-the-novel-coronavirus-and-their-effect-on-chinas

[3] Section 56, Contract Act of 1872

[4] Covid-19 Crisis: Force Majeure and Impact on Contracts From an English Law Perspective, Winston & Strawn LLP (March 25, 2020), https://www.winston.com/en/thought-leadership/covid-19-crisis-force-majeure-and-impact-on-contracts-from-an-english-law-perspective.html

[5] Peter Mulligan et al, Managing Contractual Obligations and Negotiations during Covid-19 Pandemic, Norton Rose Fulbright (March 2020), https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/7e52b826/managing-contractual-obligations-and-negotiations-during-the-covid-19-pandemic#autofootnote5

[6] Kshama Loya Modani & Vyapak Desai, Impact of COVID-19 on Contracts: Indian Law Essentials, Nishith Desai & Associates (March 23, 2020), http://www.nishithdesai.com/information/news-storage/news-details/article/impact-of-covid-2019-on-contracts-indian-law-essentials-1.html

[7] Id.

[8] Governing Law Clauses, Ashurst LLP (Feb. 12, 2020), https://www.ashurst.com/en/news-and-insights/legal-updates/governing-law-clauses/

[9] David Waldron, Timothy Cooke and David Levy, Drafing Effective Jurisdiction Clauses, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP (April 21, 2016), https://www.morganlewis.com/-/media/files/publication/presentation/webinar/ma-academy-drafting-effective-jurisdiction-clauses-21april16.ashx?la=en&hash=4D18A81549F7907747E4812196EB8C83789CB7D4

[10] Samina Iltifat & Others v. Pakistan, through Ministry of Health & Others 1989 MLD 3429, Karachi-High Court Sindh

[11] See generally the discussion in Messrs. Mansukhdas Bodarum v. Hussain Brothers Ltd PLD 1980 SC 122 and Messrs. Jaffer Brothers v. Islamic Republic of Pakistan PLD 1978 Karachi 585. See also Muhammad Sabir v. Maj. (retd.) Muhammad Khalid Naeem Cheema & Others 2010 CLC 1879

[12] Section 56, Contract Act of 1872

[13] Id.

[14] Dada Ltd v. Abdul Sattar & Co 1968 PLD Karachi 136

[15] 1984 SCMR 77 Supreme Court. Taymoor Soomro, The Contract Law of Pakistan, 226 (2014)

[16] Id.

[17]1988 CLC 171 Karachi. See also Taymoor Soomro, supra note16, 225

[18] Id.

[19] Peter Mulligan et al, supra note 6

[20] Section 65, Contract Act of 1872

[21] Taymoor Soomro, supra note 16, 290

[22] Id., 291

[23] Hueleng Tang, China Invokes Force Majeure to Protect Businesses But Companies May Be in for a Rude Awakening, CNBC (March 6, 2020), https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/06/coronavirus-impact-china-invokes-force-majeure-to-protect-businesses.html

[24]Jenny Y. Liu and Carrie Bai, Coronavirus in the Chinese Law Context: Force Majeure and Material Adverse Change, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, https://www.pillsburylaw.com/en/news-and-insights/coronavirus-in-the-chinese-law-context-force-majeure-and-material-adverse-change.html

[25] Hueleng Tang, supra note 24

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28]Jan Wolfe, Explainer: Companies consider force majeure as coronavirus spreads, REUTERS (Feb. 10, 2020), available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-legal-explainer-idUSKBN205059. Wade Coriell et al, Coronavirus and Force Majeure Declarations, Lexology (March 13, 2020), https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=fdd68e43-f688-47b7-b63e-129bf428abd6

[29] Growing Concern: What We Learned From Looking At What Chinese Contracts Say About Force Majeure, Kira Systems (2020), https://kirasystems.com/files/guides-studies/KiraSystems-Deal_Points_Force_Majeure_Coronavirus.pdf, overall sample data included 130 commercial contracts involving at least one Chinese entity, filed on EDGAR between February 2018 and February 2020, analyzed by Kira. Of 130 contracts, 94 had force majeure clauses. US SEC runs EDGAR.

[30] Peter Mulligan et al, supra note 6

[31] Laura A. Stoll et al, The Implications of Corona Virus (COVID-19) on Contractual Performance and Negotiations, Goodwin Law (March 16, 2020), https://www.goodwinlaw.com/publications/2020/03/03_16-implications-of-covid19-on-negotiations

[32] James Scott & Sons v. R&N Del Sel 1922 SC 592 (IH) 596.

Previously published in IBA Business Review. Republished here with permission.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which she might be associated.

1 comment