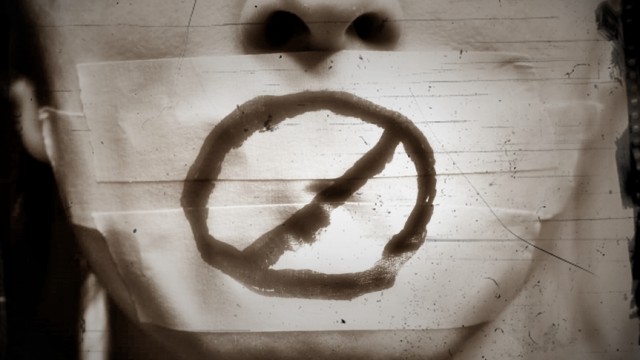

How Judiciary Has Institutionalized Curb On Free Speech

“If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear” ― George Orwell.

Freedom of speech is the sine qua non of a democratic society. It is the single most important political right of citizens. Without free speech, neither any political action is possible nor the resistance to injustice or oppression. The freely expressed opinions of citizens help restrain oppressive rule. It is futile to expect political freedom or, consequently, economic freedom in a society where free speech is strangled or curbed.

The Constitution of Pakistan guarantees freedom of press under Article 19, subject to “reasonable restrictions”. However, the freedom of the press is curtailed by the ambiguous wording of the provision, which states that:

“There shall be freedom of the press, subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam or the integrity, security or defence of Pakistan or any part thereof, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, [commission of] or incitement to an offence.”

Upon a cursory glance through the provision of the Article it becomes evidently clear that freedom of expression is not being guaranteed rather it is being denied to the citizens of Pakistan – the number and extent of qualifications and exceptions embedded in the text of the provision makes it impossible for anyone to exercise any semblance of free speech. These ‘claw back’ provisions are prima facie broad and generic.

The Article falls short of meeting international standards for the protection of the right to freedom of expression. The use of words like “reasonable restrictions” are themselves curtailing freedom, while the international standards and the rest of the world advocate “necessary” or “legitimate aim”, as well as “clear and present threat”. The muzzling of freedom of expression thus ensure that Pakistani democracy, which, in essence, is an autocracy, perpetuates its autocratic regime without being questioned by societal conscious that is its press.

The case law in terms of Article 19 was never expanded by the higher judiciary despite its scope, as is the case with US and UK jurisdictions, the judges fall short of clearly defining and expanding categories of untouchable speech or alternatively, categorically and clearly limiting certain kinds of speech and the circumstances under which they can be legitimately proscribed by the State. Instead, the courts have essentially adopted a case-by-case approach.

There are several important Pakistani judgments that underline the importance of interpreting the Constitution. For example, in Benazir Bhutto vs Federation of Pakistan case[1], the Supreme Court held that:

“Constitutional interpretation should not just be ceremonious observance of the rules and usages of interpretation but instead inspired by, inter alia, fundamental rights, in order to achieve the goals of democracy, tolerance, equality and social justice. The prescribed approach while interpreting fundamental rights is one that is dynamic, progressive and liberal, keeping in view the ideals of the people, and socio-economic and politico cultural values, so as to extend the benefit of the same to the maximum possible”.

In another case the court had observed the role of the courts is to expand the scope of such a provision and not to extenuate the same[2].

Though the courts understand the significance of free speech for the survival and sustenance of democracy, yet an overwhelming number of cases have held that such rights are not absolute, that reasonable restrictions based on reasonable grounds can be imposed, and that reasonable classifications can be created for differential treatment.

In Jameel Ahmad Malik vs Pakistan Ordinance Factories Board, Wah Cantt case[3], the court held that:

“In a democratic set-up, freedom of speech/expression and freedom of press are the essential requirements of democracy and without them, the concept of democracy cannot survive. From perusal of Article 19, it is, however, absolutely clear that above right is not absolute but reasonable restrictions on reasonable grounds can always be imposed. Reasonable classification is always permissible and law permits so”.

While dwelling on what constitutes “reasonable restriction” the courts have taken a cautionary approach and interpreted the term in a very limited manner. For example in Ghulam Sarwar Awan vs Govt of Sind[4], the court stated:

“The phrase ‘reasonable restriction’ connotes that the limitation imposed on a person in enjoyment of the right should not be arbitrary or of an excessive nature, beyond that [which] is required in the interest of the public. The word ‘reasonable’ implies intelligent care and deliberation, that is, the choice of a course which reason dictates.”

The courts in Pakistan barring a few have unfortunately played a fiddle to the atrocious state policies especially when it comes to minorities’ right to freedom of expression. Ahmedis are often denied the right to free speech under the draconian Ordinance XX of 1984 which proscribes the publication of their literature in any form. Recently, on 19 December 2015, a bench of the Supreme Court of Pakistan denied bail to the publisher of Al-Fazl, a 102-year-old Ahmadiyya publication, who is behind bars for three years on blasphemy and terrorism charges.

The courts so far have taken no suo moto notice of the National Action Plan that vows to curb free speech under the guise of national security. As per point number 11 and 14 of the rudderless plan “print and electronic media will not be allowed to give any space to terrorists”, and “social media and the internet will not be allowed to be used by terrorists to spread propaganda and hate speech, though exact process for that will be finalized”. The state policies are increasingly shifting towards strangling free media and free speech, however the courts being the guardian of fundamental rights of the people remain a silent spectator to the atrocities in the name of national security.

Catherine Anne Fraser, Chief Justice of Alberta, Canada has once said, “We have independence for one reason – to protect the rights of our citizens”. However in case of Pakistan the independence of judiciary has served little to protect the freedom of citizen of the state.

On September 9, 2014, the Supreme Court had issued contempt of court notices to anchorperson Mubashir Luqman and CEO of the ARY TV channel for allegedly maligning the judges of the apex court in a programme broadcast on May 29, 2014. The court ordered that Luqman had crossed all limits and his behavior was causing hatred against the judiciary. It also said that strict action is to be taken against any channel who allows the anchor to conduct program.

In many countries across the world, superior judiciary has already restricted the ability of government bodies, including judicial courts, elected bodies, state-owned corporations and even political parties, to bring an action against journalists for defamation. This is in recognition of the vital importance in a democracy of open disparagement of the government and public authorities, including courts. However the legal jurisprudence on the right to freedom of speech in Pakistan has yet to reach this level of maturity.

On October 28, a 19 year old blogger and political worker of Pakistan Tehreek Insaaf (PTI) was arrested by the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) for allegedly criticizing a sitting judge of the Peshawar High Court. Qazi Jalal was arrested, for his tweets against the judiciary, under the Pakistan Electronic Transaction Ordinance 2002, and is said to be still in FIA’s custody. Media reports have also stated that action against teenager Qazi Jalal has been taken on a complaint registered by unknown Pakistani citizens and he was arrested on charges of creating negative propaganda against the judiciary. Jalal has reportedly been criticizing decisions of the judiciary for a long time via his twitter account @JalalQazi.

Blasphemy is another area where the scale of justice tips against the accused. In August 2000, Justice Nazir Akhtar of the Lahore High Court stated in a public lecture that “we shall slit every tongue that is guilty of insolence against the Holy Prophet[5]”. People accused of violating Pakistan’s draconian ‘blasphemy laws’ face proceedings that are glaringly flawed. In a report published by the ICJ (International Commission of Jurists) titled “On Trial: Blasphemy Law”, it was stated that judges of the lower judiciary demonstrate bias and prejudice against defendants during the course of blasphemy proceedings and in judgments.

The courts in Pakiatn have taken a cost-benefit approach to striking a balance between preservation of freedom of speech and protecting public interest within the restrictive categories of Article 19. The courts historically have limited and curtailed the freedom of speech and press.

In Sheikh Muhammad Rashid vs Majid Nizami, Editor-In-Chief, The Nation And Nawa-E-Waqat[6] the court held:

“Article 19 provides the freedom of press subject to any reasonable restrictions which may be imposed by law in the public interest and glory of Islam, therefore, the press is not free to publish anything they desire. The press is bound to take full care and caution before publishing any material in press and to keep themselves within the bounds and ambit of the provisions of the article”.

Likewise in Syed Masroor Ahsan vs Ardeshir Cowasjee[7], the court observed that freedom of press was not “absolute, unlimited and unfettered” and that its “protective cover could not be used for wrongdoings”.

French historian Volataire had rightly said, “I do not agree with what you have to say but I will defend to death your right to say it”. The judiciary, state and legislature in Pakistan are still not ready to allow the citizens their fundamental right to speak their mind. Tolerance to criticism is the echelon of a civilized and democratic society and can’t be expected from a society whose moral fabric is torn by religious fundamentalists who have no respect for the difference of opinion.

—–

References:

[1] See Benazir Bhutto v. Federation of Pakistan, (1988) P.L.D. 416, 489 (Pak.).

[2] See Muhammad Nawaz Sharif v. Federation of Pakistan, (1993) P.L.D. 473, 674 (Pak.)

[3] Engineer Jameel Ahmad Malik v. Pakistan Ordinance Factories Board, Wah Cantt, SCMR 164, 178 (2004) (Pak.) also see Zaheeruddin and others v. The State and others (1993 SCMR 1718).

[4] P.L.D. (Sindh H.C.) 414, 418–24 (Pak.)

[5] The Daily Din, 28 August 2000

[6] P L D 2002 SC 514

[7] (1998) 50 P.L.D. 823, 834 (Pak.)

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which she might be associated.