Kulbhushan, ICJ and Pakistan – Jurisdiction and Jurisprudence

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in Hague has begun oral proceedings in the Kulbhushan Jadhav case between India and Pakistan. The ICJ had already provided its views on the assumption of jurisdiction on 8th May, 2018 when it had issued provisional measures under which Jadhav’s execution was to be held off until the final decision of the case. During the current hearing, India and Pakistan will advance arguments on the acceptability of India’s claim regarding Jadhav’s fate.

Also known as the ‘World Court’, the ICJ adjudicates disputes between states, while the Court’s jurisdiction is based upon the consent of the states, which means that the states have the option to accept or reject the Court’s jurisdiction. Once a state accords consent and the dispute falls within the scope of the given consent, the state must subject itself to the Court’s jurisdiction. Consent is accorded either through special agreements and treaties, or by accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court. Approximately 76 states, including India and Pakistan, have accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ.

So far, Pakistan has been subjected to the ICJ’s jurisdiction five times, while India has been before it six times. India has invoked the jurisdiction of the World Court against Pakistan for the second time in the Jadhav case. Prior to this ongoing issue, India had presented an appeal relating to the jurisdiction of the Council of International Civil Aviation Organization against Pakistan in 1971. The Court had ruled affirmatively on the question of jurisdiction, however, India’s appeal was referred to the Council for re-decision. Pakistan had also invoked the jurisdiction of the ICJ against India in cases involving Pakistani Prisoners of War, 1973 and the Aerial Incident, 1999. The former trial was ultimately discontinued by Pakistan while the latter was dismissed by the ICJ observing the lack of jurisdiction.

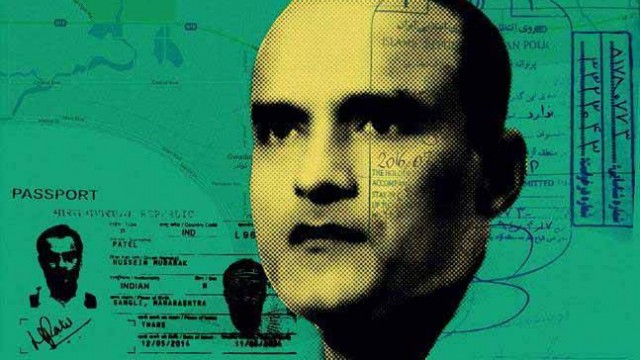

In May 2017, India approached the World Court and filed an application against Pakistan, alleging violations of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations 1963 (VCCR) in the matter of the detention and trial of an Indian national, Kulbhushan Sudhir Jadhav, who had been sentenced to death in Pakistan under the Army Act 1952. According to the Convention, foreign nationals who are arrested or detained are to be given notice “without delay” of their right to have their embassy or consulate notified of the arrest, and consular officers have the right to visit the national of such state in prison or detention and correspond with him to arrange legal representation.

India has requested the ICJ to declare the sentence awarded to Jadhav as a defiance of rights provided under Article 36 of the Vienna Convention and a defiance of elementary human rights of an accused regarding fair trial and self-incrimination given effect under Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). India has invoked the jurisdiction of ICJ basing its claim on Article I of the Optional Protocol Concerning the Compulsory Settlement of Disputes which accompanies the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (OP-VCCR).

Unlike the Marshall Islands case, where the Court dismissed the application of the Republic of Marshall Islands against Pakistan for cessation of nuclear arms, and without going into the merits of that case, in the present the ICJ has been more vocal and has assumed prima facie jurisdiction on the basis of OP-VCCR. The Optional Protocol provides that disputes arising out of the interpretation or application of VCCR shall lie within the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ and the fact is that both Pakistan and India have accorded jurisdiction to the Court with regard to disputes arising under VCCR.

The Jadhav case is the fourth case which has brought before the ICJ over alleged violations of consular rights enshrined in VCCR. The three previous cases namely Angel Breard, LaGrand and Avena had been decided at different times by the ICJ against the USA and had also been about non-provision of consular access to arrested individuals facing the sentence of death penalty. Despite the stay of execution of the death sentences by ICJ, the US hanged the convicts in all three cases. Though the Breard case had later been discontinued by Paraguay, LaGrand and Avena had been fully litigated upon by Germany and Mexico respectively. Annoyed by the United States’ actions, ICJ declared that the US had violated VCCR by not granting consular access to the detainees and held that the United States of America should review and reconsider the convictions and sentences by taking account of the violation of rights set forth in the Convention. Compliance by US to the verdicts of ICJ remained grim. In fact, the US reacted by painting the decisions as an interference with its sovereign rights and withdrew from the OP-VCCR, thus evading the jurisdiction of the Court.

By indicating provisional measures on India’s application, the ICJ has declared the Jadhav case to be similar to the LaGrand and Avena cases. During the hearing of the case, both India and Pakistan will advance their oral arguments based on the already submitted memorial and counter-memorials. Judgment will be pronounced subsequent to the deliberations of all judges sitting on the Bench. The sitting Bench of the ICJ also includes a permanent Judge of India while Pakistan’s only representation is through an ad hoc judge for the case and both may have bearing on the Court’s final decision. Keeping in view the traditional rivalry between Pakistan and India, ICJ’s decision is expected to have far more political implications than legal ones for either country.

A bare reading of the provisional order of the ICJ given on 8th May, 2018 reveals that although the Court has declared the Jadhav case to be identical to cases it has previously adjudicated upon, Pakistan is still required to argue that the present case is different on account of certain reasons discussed below in order to get a more favorable verdict.

Firstly, Jadhav is not an ordinary Indian national but admittedly an officer of the Indian Navy involved in subversive and terrorist activities in Pakistan. Although VCCR does not distinguish between the arrests of spying agents and ordinary citizens, it does mention that the provision of consular assistance is subject to the laws and regulations of the receiving state.

Secondly, the Agreement on Consular Access signed between India and Pakistan was recognized by the Court in its May 2017 decision, though the Court reserved to consider it at the merits stage of the case. Article 73, VCCR establishes the Convention’s relationship with other international agreements. It does not preclude states from concluding agreements confirming, supplementing, extending or amplifying the provisions thereof. Pakistan can argue that the said Agreement elaborates the understanding of both parties on the issue of extending “consular facilities” to detainees on each side. It categorically mentions that, “…in case of arrest, detention or sentence made on political or security grounds, each side examines the case on its merits,” which leaves little room for the Court to interfere into the security matters of a sovereign state. The Agreement is effective and the list of detainees is exchanged twice on January 1st and July 1st every year. Neither did such agreements exist between the US and other states, nor did the convicts serve as spies in the previous cases decided by the Court.

Thirdly, unlike the US, Pakistan is a dualist state, which means that international treaties do not become binding ipso facto and only become the law of the land if given effect through domestic legislation. The Diplomatic and Consular Privileges Act 1972 gives effect to some provisions of the VCCR but not Article 36 thereof. Therefore, being a sovereign state, Pakistan has discretion under its laws to grant consular assistance or any request made for consular assistance.

Fourthly, the ICJ is not a competent forum to consider India’s request to declare the sentence of Kulbhushan Jadhav violative of Article 14 of ICCPR. Pakistan should argue before the ICJ that the disputes between states falling under the scope of ICCPR do not come within its purview rather they fall under the Committee set under Article 41 of ICCPR.

Last but not the least, Jadhav’s trial was conducted by a court established under Pakistan’s Army Act 1952 and not by any special court or forum. The said Act also provides a list of persons who can be tried and Jadhav falls under it. The trial did indeed fulfill the conditions of being a fair trial as it was done in an open court, had an independent judge, granted the right of appeal and gave the accused the right to seek representation.

ICJ is not a court of criminal appeal, therefore, the India’s request to quash criminal proceedings and repatriate Jadhav seems to be based on false hopes as the World Court is not empowered to order the release of any convict.

In case the Court considers Jadhav’s case in light of the jurisprudence established in LaGrand and Avena, it may direct Pakistan to not only provide consular access to Jadhav, but to also ‘reconvene the trial’ with counsel of his choice.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which she might be associated.

Excellently & Intelligently drafted with precise content..????