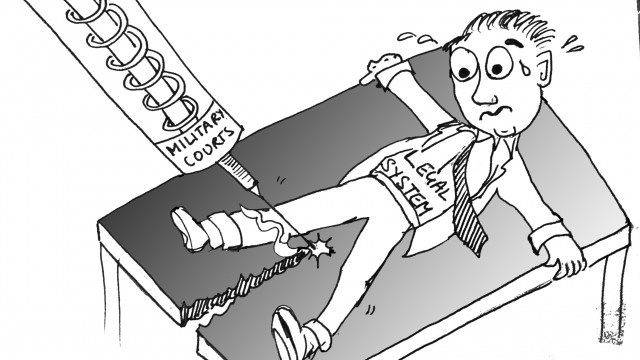

The status of civil liberties is a fair measure of the rule of law prevalent in a society. The liberties and freedoms of a people, however, depend upon the political framework that regulates social order. Pakistan is no exception; a military justice system runs parallel to the civil or ordinary courts of justice, generally unnoticed, as it does in many other countries having a better civil rights record. It is only when military justice formally reins in civilians that one hears cries of denial of rights. The events of May 9 have also triggered this realisation.

We live in a rare legal order – a hotchpotch of selective common law principles and Islamic law and traditions where civil liberties are defined less frequently by our chosen representatives and more definitely by de facto powers. The Constitution of Pakistan adopts trichotomy as a model for parliamentary democratic governance, where military administration is subservient to the executive branch but the confluence of military ideology and state governance certainly exists as well. Furthermore, whenever the Supreme Court has heard a challenge in this regard, it has also confirmed the nexus (with occasional dissent).

Public expectation, nevertheless, still heightens when judges make statements emphasising their oath and taking their independence seriously. At a time when the overstretch of military-hold has been perceived by many, the recent trial of civilians by courts-martial, many have thought, is an issue that would get the attention of the full court which would seize the opportunity to not only allay internal administrative dysfunction but, hopefully, reckon time to undo the past precedent of validating military overreach, including civilian trial by a court-martial.

What are the odds of a favourable ruling this time? Before placing your bets, consider the following:

(i) while the judiciary struggles with its core values (particularly administrative cohesion, independence and impartiality), the military administration has regrouped with a united focus over its core values (particularly discipline and morale);

(ii) the military administration harnessed the support of Parliament (which the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) surrendered voluntarily), while the judiciary came at the Parliament with knives out; and

(iii) the men in uniform did the unthinkable: held their own accountable, whereas the men in robes appeared to have rendered internal accountability redundant to harbour their own.

To say that the opposition to trial of civilians by courts-martial has moorings in public conscience is not a lie! The initial resistance had been spearheaded by keyboard warriors who declared open season on the military, deriding it on social media. When they failed to mobilise support on ground locally, they sought condemnation from an international audience. Without much success there as well, the scene shifted to the Constitution Avenue in Islamabad. A pro-Imran Khan, People’s Party stalwart (uncharitably labeled renegade) and a former Chief Justice of Pakistan (likewise labeled eccentric) joined the efforts of another legal maestro (a founding member of the PTI) known for his opposition to ‘military courts’, attacking the historically and constitutionally accepted military justice system itself by invoking the controversial jurisdiction of the Supreme Court under Article 184(3) of the Constitution.

A summary of the legal arguments, simply put, is this:

- One: since 1987, civilians cannot be tried by courts not subordinate to the judiciary, as the executive stands separated therefrom (according to art.175(3)). To hold that fair trial and due process are fundamental rights (art.10A) bolsters this position. Courts-martial are headed by executive officers (of non-judicial cadre), hence, violate the Constitution in letter and spirit. In this regard, prior precedent (mainly the FB Ali case) is irrelevant (see the ‘complete bar analysis’ below); or

- Two: the court must revisit earlier precedent validating civilian court-martial such that civilians may only be tried by courts-martial when the state is at war, or warlike circumstances prevail, or temporary measures (in the nature validated in the Liaquat Hussain case) exist. May 9 offers no such happenstance (see the ‘restricted application approach’ below); and/or

- Three: the Jinnah House, commemorative statues of martyred soldiers and other sites attacked are not ‘military installations’ or places that adversely impact ‘military operations’. Nonetheless, it is a serious matter! Let the ordinary courts, including anti-terrorism courts, try the perpetrators and, where due, administer harsher punishments (see ‘technical exclusion’ below).

Underscoring these arguments is the point that the Army Act is an archaic law. It was essentially designed to cater to violations by military personnel only, who have agreed to abide by such norm. Civilians, on the other hand, have not contracted out of the jurisdiction of ordinary courts.

Let’s consider each argument in detail.

The Complete Bar Analysis

Realpolitik (which impedes acceptance) aside, the first argument looks beyond the historical and constitutional basis of a parallel military justice system post-1987. For instance, the Shariat Appellate Bench of the Supreme Court in 1989 validated the Army, Navy and Air Force Acts as compatible with the injunctions of Islam, after appellate procedures had been incorporated therein by amendment required by the Federal Shariat Court in 1985 without a carve-out for civilians. To hold that such laws now be declared unconstitutional (even in the absence of a charged atmosphere in the armed forces) appears radical. Nevertheless, such line of argument draws traction from the constitutional emphasis on the separation of judiciary from the executive (art.175(3)), as outlined in the discussions in Liaquat Hussain with reference to the military acting in aid of civilian authority (art.245) and the dissenting view of Isa, J in DBA, Rawalpindi (art.4 and 8(3)) in the following words:

“…the Constitution does not permit the trial of civilians military as it would contravene Fundamental Rights.”

Importantly, the court has never held or suggested that the establishment and operation of courts-martial is unconstitutional. While it is true that the matters relating to civilians which the courts-martial may take on have been the subject of judicial consideration, including in 1999 (Liaquat Hussain) and again in 2015 (DBA, Rawalpindi), the facts and circumstances of each are distinguishable. With regard to the violation of fundamental rights, the underlying point which has not been reconciled is that almost all fundamental rights (except for a citizen’s right to remain in Pakistan (art.15) and the right to profess or practice a particular religion (art.20)) remain subject to law. Moreover, such broad-brush consideration distances itself from the jurisprudence here and abroad according to which courts-martial are no longer considered an ‘instrumentality of the executive’. The military justice system’s attributes vis-à-vis fair trial and due process considerations when compared may show that:

(i) in both military and civilian courts, the burden of proof (i.e. beyond reasonable doubt) rests with the prosecution;

(ii) where life or liberty is at risk by way of punishments, the defendant has a right to counsel;

(iii) the defendant is properly confronted with the charge against him or her along with material relied upon, including a list of witnesses;

(iv) the defendant has the right to cross-examine as well as lead own evidence; and

(v) the convict has recourse to appellate remedies in the first instance and later through the civil justice system by invoking the writ jurisdiction of the High Court.

The Restricted Application Approach

The second argument appears more palatable, though it does have practical impediments to begin with. The earlier precedents affirming civilian court-martial had come from benches larger than the current six-member bench. Nine judges in Liaquat Hussain (1999) validated the five-member decision in FB Ali (1975). In DBA, Rawalpindi (2015), by eleven-to-six majority, the full court dismissed the challenge to the Army Act. Hence, neither Liaquat Hussain nor DBA, Rawalpindi displaces the validation of army laws or creates any exceptions to, or overrules, FB Ali. Initially, when a nine-member bench had been constituted (full court disappointment aside), there had been an academic possibility that a unanimous opinion of the court could turn the tide, but when ‘independent minded’ judges recused themselves (over hyper technical grounds, some suggest), the chance was missed. Now that Afridi, J has reinvigorated the point of assembling a full court (presently 15 of 17 in total), let’s see how the cookie crumbles!

Additionally, there are issues with this argument on merits as well. For instance, the military laws in question provide for their application to civilians and numerous cases of civilians have been dealt with by courts-martial while their decisions have not been undone by the courts. To do so, the recognised grounds available are:

- coram non judice (‘not before a judge’);

- without lawful authority; or

- mala fide (‘in bad faith’).

Besides, only when a charge is framed can one conclusively consider whether or not these laws have been rightly applied. A carve-out for civilians cannot be drawn hypothetically. This could mean that the petitions are either premature or will need amendment (as in FB Ali) once civilian court-martial commences before the court concludes hearing such petitions. Most importantly, the argument misconceives that a court-martial is assembled during wartime only. For court-martial jurisdiction over civilians to be well-founded, international and domestic precedent suggests that only a ‘sufficient connection’ to the military is required.

Technical Exclusion

The last leg of the argument misses the point. The term ‘military installation’ is of broad connotation. It means and includes any activity or facility under the control of the military administration. It need not be relevant to ‘active’ military operations. Even premises leased for housing purposes are covered, as are peacetime installations. It is the context in which a place or activity is attacked. Technical arguments, including the video evidence in question and the like, are not relevant for assessment in such petitions. These may be of use in trial or post-trial proceedings before the High Court. Most importantly, ‘military ideology’ is not an easily displaceable commodity. In this regard, the commemorative memorabilia and statues of martyrs are, perhaps, the highest form of symbolism (discipline, morale, honour, sanctimony – all rolled into one). It is unlikely that the court will entertain any notion that could minimise any core value of military ideology.

Lastly, appealing to the conscience of the court that military justice must cede space to the ordinary courts has suspect bearings. The claim that somehow the civilian justice system delivers assured constitutional guarantees is misplaced. Delay, for instance, is a most striking feature of civilian justice. It is intolerable in military justice, for delay can have a devastating impact on morale and discipline. Misgivings of all and sundry about the civilian justice system are no secret, including the concern regarding ‘approachability’. These lacking aspects provide no justification for validating courts-martial, but must one juxtapose it with the state of the civil system of justice?

It is remarkably disappointing for the petitioners that the next date of hearing will not be before mid-July, while no interim order comforting the perpetrators has been issued either. However, expectations have been aired! It is ominous to learn that the personal or even professional commitments of members of the court prevent them from assembling sooner to hear the petitions. Stakeholders, including a former Chief Justice, a Senator and a Governor will have to wait or come up with something else to tip the scales. For the stalwart PTI litigator having trouble getting his or her petition even listed for a hearing is an additional indicator.

The only good news for the petitioners is that, on the last date of hearing, the Attorney General had informed the court that no punishment of ‘death’ or ‘long’ imprisonment was to be expected.

The crystal ball does not reveal much promise. All arrows point to the court balancing accented sensitivities of the military administration and its own commitment to uphold the rule of law. It will highlight the importance of military ideology and reconcile elements of fair trial and due process accordingly. It might throw in the expectation that a court-martial in this day and age cannot remain oblivious to constitutional guarantees in the determination of individual rights and liberties, when military top brass itself assures commitment to our constitutional order. And that the convicts are afforded appellate remedies and eventually able to knock on the door of the High/Supreme Court which will act to ‘preserve, protect and defend’ the Constitution.

Yes, your eyes! Keep ‘em open

Danger lurks; for all to see

In so dark a night we’re woken

Simply cannot bank on me!

Didn’t walk the talk, we ‘Lords of Crown’

Let demon seek, our hearts malign

No caution served our oath or gown

Quickly selfish gains align

All eyes again on apex court

Hopeful some, but more distraught

Will they fall or hold their fort

Marches again the juggernaut!

In the post-May 9 scenario, the judiciary has been under scrutiny in manner, detail and expectation like never before. How will the court react? Or, being the realist that it has been, simply adjust?

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which he might be associated.