On 23rd October, 2023, a 5-member bench of the honourable Supreme Court of Pakistan announced its ‘short order’ in the case Jawad S. Khawaja and others versus the Federation of Pakistan and others in which it declared the trials of civilians by military courts ultra vires to the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973. At the time of this writing, the detailed judgment containing the reasons based on which the Supreme Court reached this conclusion is yet to be released, however, we can try to fairly anticipate what will be contained in that detailed judgment.

The short order contains three points:

- 4 judges have declared sections 2(1)(d) and 59(4) of the Pakistan Army Act, 1952 ultra vires to the Constitution, with 1 member of the bench dissenting.

- All 5 judges have declared unconstitutional any trials/proceedings that have been taken by military authorities against an estimated 103 individuals in relation to the attacks that occurred on 9th/10th May, 2023.

- Such cases be transferred to the relevant civilian courts.

Factual Background

Large scale riots and arson took place in different parts of Pakistan on 9th and 10th May, 2023 following the arrest of the former Prime Minister Imran Khan from the Islamabad High Court on 9th May, 2023. According to some, they were peaceful protests by supporters of the former Prime Minister. Nonetheless, a crackdown started against the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) in the aftermath of these attacks. It was announced that those involved in the attacks would be tried by military courts under the provisions of the Pakistan Army Act and the Official Secrets Act, 1923. Following this, many petitions were filed in the Supreme Court under Article 184(3) of the Constitution challenging the decision of the federal government to subject civilians to military trials.[1]

Past Jurisprudence on Trials of Civilians in Military Courts

In the case F. B. Ali and another Versus the State,[2] a 5-member bench of the Supreme Court declared trials of civilians under Section 2(1)(d) of the Pakistan Army Act to be legal. The Supreme Court held that the only nexus that needed to be established for “civilians or persons who have never been, in any way, connected with the Army” to be subject to the Pakistan Army Act was that “they should be persons who are accused of seducing or attempting to seduce any person subject to the Army Act from his duty or allegiance to the Government.”

In the case Darwesh M. Arby Versus Federation of Pakistan,[3] the honourable Lahore High Court while interpreting the provisions of the Pakistan Army (Amendment) Ordinance, 1977 (subsequently, the Pakistan Army [Amendment] Act, 1977) noted the following:

- The purpose of military courts was to maintain discipline within the armed forces.

- In case the armed forces were called and military courts set up, there had to be a nexus between the offences being tried and the jurisdiction of the said military courts. The Lahore High Court elaborated this by drawing a comparison with England and said that the nexus that needed to be established was that the law and order situation had deteriorated to such a point that normal civilian courts could no longer function the way they were supposed to.

- In this particular case, the Lahore High Court also gave examples of how military courts were conducting trials of criminal cases that had no nexus with law and order.

- The Lahore High Court noted that, as per the law in question, giving discretionary authority to army officers to transfer cases from military courts to civilian courts resulted in a situation in which the armed forces were – instead of acting in aid of civil power – “acting in supersession and displacement of the same.”

One of the leading cases on the topic of trials of civilians in military courts is Liaquat Hussain Versus Federation of Pakistan.[4] In this case, a 9-member bench of the Supreme Court declared trials of civilians in military courts under the Pakistan Armed Forces (Acting in Aid of the Civil Power) Ordinance, 1998 to be unconstitutional. In short, the Supreme Court based its judgment on the following points:

- Military courts are part of the armed forces, which are part of the executive. The executive cannot be allowed – as per the doctrine of trichotomy of powers/separation of powers envisioned under the Constitution – to assume the powers of the judiciary.

- If a forum that is unconstitutional gives a verdict which deprives a person of life [or liberty] i.e. if such a forum sentences a person to death or imprisonment, such a verdict would violate Article 9 of the Constitution.[5]

- In the context of the Ordinance of 1998, the authority of the federal government to pick-and-choose which accused are to be tried by military courts and which in civilian courts without any clear criteria to distinguish between the two violates Article 25 of the Constitution.[6]

The other leading case in this regard is District Bar Association Rawalpindi Versus Federation of Pakistan.[7] The background of this case is that after the APS attack of December 2014, Parliament passed laws, including the Twenty First Amendment to the Constitution, enabling trials of terrorists in military courts. The constitutional validity of such laws was challenged in the Supreme Court. A full court heard the case and, by an 11-6 majority, declared the laws to be constitutional. The following are some important points from this judgment:

- The situation in Pakistan was one of war and the armed forces were authorized by the Constitution to defend Pakistan in times of war.[8] Thus, military courts, which were part of the armed forces, could exercise jurisdiction in such cases.

- The Twenty First Amendment to the Constitution contained a sunset clause i.e. the said Amendment would lapse after 2 years.[9]

- The Supreme Court did not give carte blanche to the military courts to try all civilians, but only those who fulfilled the criteria mentioned in point (1) above.

Expected Detailed Judgment

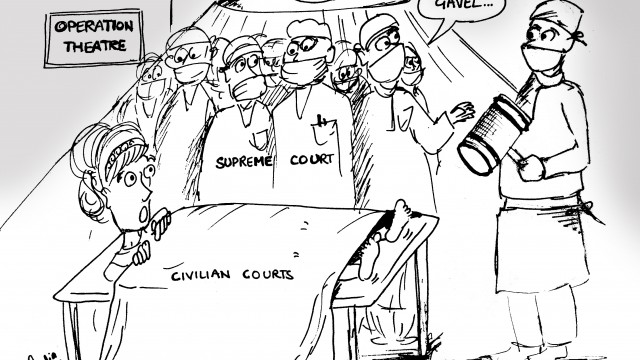

In my view, the detailed judgment to be released by the Supreme Court will be similar to the judgments rendered in the Liaquat Hussain case and the Darwesh Arby case cited above. The Supreme Court is likely to hold, in my view, that conducting trials of civilians in military courts violates the doctrine of trichotomy of powers, infringes on the independence of the judiciary and violates the provisions of the Preamble to the Constitution.[10] The Supreme Court has also held in past cases that the independence of judiciary is a right under Article 9 of the Constitution[11] and allowing trials of civilians in military courts would violate Article 9.

Based on the publicly available discourse, the Supreme Court, in all likelihood, is going to reiterate that allowing military courts to conduct criminal trials of civilians will result in a situation in which the armed forces instead of acting in aid of civil power[12] are actually replacing it. It will be declared violative of Article 245(1) of the Constitution and, by extension, the rights guaranteed under Articles 4 and 10 of the Constitution.

Another legal possibility is that since not all trials related to the carnage of 9th/10th May, 2023 are being conducted in military courts, the Supreme Court, reiterating its earlier view in the Liaquat Hussain case, will likely declare a violation of Article 25 of the Constitution.

Dissenting Note

As mentioned in the beginning, the decision to declare sections 2(1)(d) and 59(4) of the Pakistan Army Act as unconstitutional was taken by a 4-1 majority. This begs the question of what the dissenting note will be of the honourable judge who disagreed with the majority. In my view, the dissenting note will hold that trying to seduce rebellion within the armed forces is a crime and since military courts have a direct nexus with the armed forces, they can exercise jurisdiction in such cases.

On the other hand, all 5 judges have ordered that the trials/proceedings conducted against an estimated 103 individuals related to the attacks that occurred on 9th/10th May be transferred to the relevant civilian courts. This means that even the dissenting judge who declared sections 2(1)(d) and 59(4) of the Pakistan Army Act to be intra vires to the Constitution ordered the above-mentioned trials/proceedings to be transferred from military courts to civilian courts. In my view, the likely reason for the dissent will be that the nexus required to be established to invoke the provisions of sections 2(1)(d) and 59(4) of the Pakistan Army Act has not, in the present cases, been seen to have been established.

Impact(s) of This Case

It can safely be assumed that this judgment is going to have far-reaching consequences. The majority decision has effectively closed all legal avenues for people who are not directly connected with the armed forces from being subjected to criminal trials within military courts. This raises the following questions:

- Will trying to incite rebellion within the armed forces be a criminal offence?

- If so, where will the trials of those accused of such offences be conducted?

The answers to the above-mentioned questions are simple: there is an entire chapter in the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), 1860 titled, “Of offences relating to the Army, Navy and Air Force.”[13] This chapter covers 11 sections,[14] two of which categorically declare “abetting mutiny or seducing a soldier sailor or airman from his duty” to be criminal offences.[15] In addition, as per the Pakistan Penal Code, “abetting” includes instigating.[16] Thus, if a person instigates a member of the armed forces to commit mutiny, such person can be subjected to a criminal trial as per the already existing law of the land.

As far as the question of where such trials will be conducted is concerned, the answer can be found in Schedule II of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1898.[17] The trials of individuals accused of having committed the offences defined in sections 131 and 132 of the Pakistan Penal Code will be conducted in the Court of Sessions (or Sessions Court). Trials of other offences mentioned in Chapter VII of the Pakistan Penal Code will be conducted, depending on the offence, either in the Sessions Courts or Courts of Magistrates.[18] The existing law of the land seems to have ample room to hold accountable individuals involved in trying to incite mutiny/rebellion within the armed forces.

Concluding Thoughts

The judgment in the case at hand is no doubt a landmark moment in the constitutional history of Pakistan. However, there are two sides of the coin. One version is that, by declaring unconstitutional the trials of civilians in military courts, the Supreme Court has upheld the Constitution and ensured a mechanism to prevent a number of fundamental rights of the citizens of Pakistan from being legally violated. The other side of the story revolves around the question of why, throughout the history of Pakistan, the need for conducting criminal trials in military courts has been felt. The answer very clearly seems to be that civilian courts do not do justice thereby necessitating the need for military courts.

Pakistan – especially the judiciary – is at a juncture with two routes ahead and it has to choose one of the two:

- either hardcore criminals be allowed to commit crimes with a great deal of impunity, as one avenue for holding them accountable legally has been closed; or

- the judiciary to take the momentum forward, commit itself to reform and ensure that ground realities are such that the arguments in favour of conducting trials of civilians in military courts become a relic of the past.

May God Almighty help the State of Pakistan make – and more importantly, implement – the correct decision.

References

[1] Under Article 184(3) of the Constitution, the Supreme Court can give a decision on any question of Public Importance concerning the Fundamental Rights guaranteed by the Constitution

[2] PLD 1975 SC 506

[3] PLD 1980 Lahore 206

[4] PLD 1999 SC 504

[5] Article 9 of the Constitution, titled Security of Person, says that a person can only be deprived of life or liberty if such is committed as per law.

[6] Article 25 of the Constitution, titled Equality of citizens, says that all citizens are equal before the law and shall enjoy equal protection of the law.

[7] PLD 2015 SC 401

[8] Article 245(1) of the Constitution

[9] The said Amendment was extended for a further 2 years in 2017 by way of the 23rd Amendment to the Constitution. It was not extended after that

[10] The Preamble to the Constitution, inter alia, says “Wherein the independence of the judiciary shall be fully secured”.

[11] Baz Muhammad Kakar Versus Pakistan, PLD 2012 SC 923; Riaz ul Haq Versus Pakistan, PLD 2013 SC 501

[12] Article 245 of the Constitution allows the Armed Forces to “act in aid of civil power when called upon to do so” by the Federal Government.

[13] Chapter VII of the Pakistan Penal Code

[14] Sections 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 138A, 139, and 140 ibid

[15] Sections 131 and 132 ibid

[16] Section 107 ibid

[17] Schedule II of CrPC contains details, inter alia, of the Courts having jurisdiction to conduct trials of the offences mentioned in the Pakistan Penal Code.

[18] These two categories of Courts have been defined in Chapter II of CrPC.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which he might be associated.