In April 2011, France became the first country in the European Union to enact a law banning full-face covering in public spaces.[1] Following France, Belgium also introduced a law banning the wearing of clothing which partially or completely covered the face.[2] The law of both countries regarding face-covering came to be known as the ‘burqa ban’.

Before going into a detailed discussion, it is important to look further into the face-covering laws passed by both France and Belgium and the reasons put forth by them to support such laws. In France, the National Assembly and Senate adopted the law and the President of the Republic promulgated Act No. 2010-1192 of October 11, 2010 banning the dissimulation of the face in public spaces. Article 1 of the law states the following:

“No one may, in the public space, wear an outfit intended to conceal his face.”[3]

Likewise, the Government of Belgium on 11th June, 2011 passed an “Act to prohibit the wearing of any clothing that conceals the face”. Under Article 2 of the law, Article 563bis had been inserted in the Penal Code[4] which stated the following:

“…shall be punished by a fine of fifteen euros to twenty-five euros and imprisonment from one day to seven days or one of those penalties only, those who, unless otherwise required by law, shall appear in places accessible to the face masked or concealed in whole or in part, so that they are not identifiable.”[5]

An important question that arises in relation to the aforementioned laws is whether the laws banning face-coverings passed by France and Belgium are compatible with their international human rights commitments since both countries are signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), according to which France and Belgium are under an obligation to protect the fundamental human rights of their citizens. This question will be answered in due course.

Legislative documents supporting the ban suggest that numerous ‘reasons’ or ‘aims’ had been brought forward in defence of restricting face-covering in public places but three main aims stood out:

- The first one concerned public safety;

- The second one concerned living together in a community (or le vivre ensemble in French);

- The third one concerned women’s rights. The promotion of gender equality and the protection of rights and freedoms of others had also been included within the aims, in support of banning face-covering in public spaces.

The ban on face-covering in public places in France and Belgium affected a segment of Muslim women, specifically those using different face-coverings for religious purposes, therefore, the ban raised some significant legal questions. Consequently, the laws banning face-coverings were challenged for their legality, particularly for the violation of Article 3 (against inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment), Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life), Article 9 (freedom of thought, conscience and religion), Article 10 (freedom of expression) and Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of the ECHR. The stance taken by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) on whether the laws banning face-covering violated human rights has been discussed below.

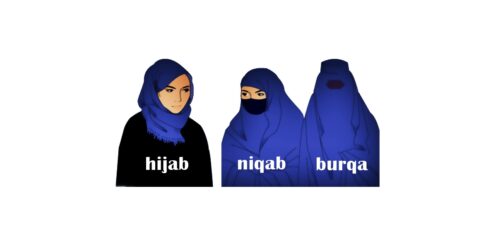

In the famous case of SAS vs France[6] the applicant was a French national who was a devout Muslim. She complained that she was no longer allowed to wear a full-face veil in public places following the entry into force, on 11 April 2011, of the law prohibiting concealment of one’s face in public places. In her submissions, she said that she wore the veil (i.e. niqab and burqa) as per her religious faith and personal beliefs. A burqa covers the full body and includes a thin cloth over the face while a niqab covers the full face except for the eyes. The applicant complained to the ECtHR that she was unable to wear the veil in public places as it had been banned by the French government and that such a ban not only discriminated on the grounds of religion, sex and ethnic origin, it was also detrimental to women who used the full-face veil. She claimed that Articles 8 and 9 in conjunction with A.14 of the ECHR had been violated. On the other hand, the French government submitted that the purpose of prohibiting face-coverings in public places was to foster social ties and promote the principle of ‘living together’.

The case held that,

“… the ban imposed by the Law of 11 October 2010 could be regarded as proportionate to the aim pursued, namely the preservation of the conditions of ‘living together’ as an element of the ‘protection of the rights and freedoms of others’. The impugned limitation could therefore be regarded as ‘necessary in a democratic society’. That conclusion held true with respect both to Article 8 of the Convention and to Article 9. Accordingly, there had been no violation either of Article 8 or of Article 9 of the Convention”[7] and also “… there had been no violation of Article 14 of the Convention taken together with Article 8 or Article 9 of the Convention.”[8]

The cases of Popa v Romania [2013] ECHR 4233/09 and DH v Czech Republic [2007] ECHR 57325/00 were also considered.

In SAS v France,[9] the applicant also complained that French laws banning full-face coverings imposed a fine of 150 euros and/or mandated taking part in citizenship education,[10] and awarded a sentence of imprisonment and fine of 30,000 euros to anyone who compelled another person to wear face-coverings in public,[11] therefore, by wearing a full-face veil she would expose herself not only to the risk of sanctions but also to the risk of discrimination and harassment, which she argued were degrading treatments under Article 3 of the ECHR:

“No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment.”[12]

The applicant in SAS further complained that the face-covering laws passed by the French government also violated Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of ECHR, considering it together with Article 3.

The ECtHR observed that,

“…the minimum level of severity required if ill-treatment is to fall within the scope of Article 3 is not attained in the present case.”[13]

The ECtHR held that under Article 35(3)(a) of the ECHR, the complaint filed by the applicant was manifestly ill-founded. The ECtHR further concluded that the facts of the case did not fall within the domain of Article 3 of ECHR and so the applicant could not rely on Article 14 of ECHR in conjunction with Article 3.

According to Millet,

“…the outcome of the case may be considered as defeating the rights of Muslim women in France to express their religion, however, there are aspects of the decision which ought to be celebrated as furthering the protection of human rights.”[14]

Let us compare the reasoning provided in SAS v France[15] with the case of Dahlab v Switzerland:[16]

“…the applicant complained to the ECtHR that the prohibition on wearing a headscarf infringed her freedom to manifest her religion, as guaranteed by Article 9 of the ECHR and amounted to discrimination on the ground of sex within the meaning of Article 14 of the Convention, in that a man belonging to the Muslim faith could teach at a state school without being subject to any form of prohibition was prevented from wearing an Islamic headscarf in the performance of her teaching duties.”

The ECtHR held that the hijab “appears to be imposed on women by a precept which is laid down in the Koran.”[17] Therefore, the decision did reflect that the court tried to move away from earlier jurisprudence which appeared rife with assumptions about Islam in a general sense rather than representing the protection of expression of individual freedoms.[18] However, the ECtHR further held that interfering with the applicant’s freedom to manifest her religion was justifiable and proportionate because the measure was aimed to protect the freedoms of others, especially schoolchildren, and that the same measure could also have been applied to a male in similar circumstances. The ECtHR accordingly held that there had been no discrimination on the grounds of sex and dismissed the application for being manifestly ill-founded under Article 35(3)(a) of ECHR.

Similarly, in the case of Leyla Şahin v. Turkey,[19] Istanbul University informed its students that wearing headscarves and maintaining long beards would not be permitted within the university. Leyla Sahin, one of the students, complained to the ECtHR that the ban in Turkey violated her rights under Articles 8, 9, 10, and 14 of ECHR. The ECtHR found no violation of Article 9 and other Articles of the ECHR and reasoned that Turkey’s ban on headscarves had been necessary to protect “public order” and the “rights and freedoms of others”, therefore it was legitimate for the Turkish university to ban the wearing of headscarves on its premises.

The ECtHR cited the case of SAS in the reasoning almost seventeen times. However, it completely ignored the fact that France and Turkey were different in political, economic and many other contexts. For instance, in the case of Şahin, the ECtHR stated that in democratic societies with different religions co-existing at the same time, the state might find it necessary to put certain restrictions on the freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs in order to protect the interests of other groups and ensure respect for their beliefs as well.[20] It is also pertinent to mention that Islam had been the majority religion in Turkey and minority religion in France, a fact which the ECtHR did not seem to take into consideration.

During the proceedings of the Şahin case, ECtHR indicated that face-covering in Turkey was being encouraged by a conservative Islamist movement. In such a situation, the restriction on headscarves imposed by the Turkish government was likely to be justifiable on the grounds of gender justice. Conversely, face-covering was not part of the central culture in French society and women might have been wearing the veil for different reasons than those in Turkey. For instance, in French society, the veil could be considered a declaration of identity in a culture where Muslims had been a religious minority.[21] Even though the ECtHR in SAS purported to reject France’s claim that the ban promoted gender equality, by relying on Şahin it appeared to believe that the prohibitions on veiling promoted women’s equality.[22]

In Belgium’s twin cases Dakir v. Belgium[23] and Belcacemi and Oussar v. Belgium,[24] the applicants filed a complaint after Belgium passed laws banning full-face veils. The ECtHR rejected the complaints regarding breaches of Articles 8 and 9 of the ECHR submitted by the applicants who had been affected by restrictions on the ability to wear a niqab/face-covering. The ECtHR cited the case of SAS and held that the ban on full-face veils did contravene Articles 8 and 9 but could be allowed in order to enhance people’s ability to “live together” pursuant to the “protection of rights of others”, therefore the court found no violation of any Article of ECHR.

In light of the case-law mentioned above and the decisions of ECtHR, it would not be wrong to suggest that the reasons provided by ECtHR to justify the ban on face-covering have been ambiguous and have created an undesirable situation where other Member States of the European Union intending to impose a ban on face-covering(s) based on imprecise and vague policy aims could do so without even considering the protection of individual rights. Short decisions of the ECtHR indicated that the ban was lawful and the French/Belgian laws banning full-face covering did not violate any human rights. On the other hand, the United Nations Human Rights Committee found that the laws passed by the French government to prohibit full-face covering in public spaces violated religious freedoms of Muslim women and also stated that France had not adequately explained why it had been necessary to prohibit face-covering veils.[25]

Referring to the ‘legitimate aims’ or objectives that France and Belgium tried to achieve by banning the full-face veil, it was argued that the ban was necessary to promote public safety and public order because a person in a public space should be identifiable at all times.

According to Evans,

“…to be considered as a legitimate aim to restrict human rights, feelings of unsafety must be objectively founded…”[26]

Consequently, it is not fair to stop someone from practising one’s religion merely on the basis of a group of population finding it offensive or frightening.[27] The ECtHR, while acknowledging that face-covering might harm public safety, also accepted that the full-face covering had so far not created any real safety issues. Similarly, the Conseil d’Etat (the highest administrative jurisdiction in France)[28] also observed that the full-face veil had not created any specific problems to public security or disturbed public order to justify a general ban. Such a ban would, therefore, rest upon an artificial preventive logic that had never been endorsed by case-law.[29]

Moreover, the aim to promote public safety by banning full-face covering had been supported by examples based on mere fears or worries. For instance, an argument was put forward that someone could easily hide weapons underneath the garments which could allegedly pose a safety risk, thereby justifying a ban on full-face covering. In Leyla Şahin v. Turkey,[30] Françoise Tulkens stated the following in her dissenting opinion:

“… mere worries or fears would not justify interference with a right guaranteed by the ECHR because to prove a ‘pressing social need’ the state needs to provide indisputable facts and reasons whose legitimacy is beyond doubt.”

It had also been argued by France and Belgium that the ban on full-face veil was necessary to promote and not undermine the concept of “living together” in a democratic society as the face played a vital role during social interaction. It seems strange to justify a violation of the freedom of religion with the right to privacy. It also indicates that the state can force people to communicate with each other in public as well as decide what sort of communication should take place in order to be valuable or democratic. It is submitted that in order to give respect to democratic values, states should leave it to the individuals to decide how and when they want to communicate with other citizens.

In SAS v France,[31] the two dissenting judges argued that,

“…the very general concept of “living together” does not fall directly under any of the rights and freedoms guaranteed within the Convention. Even if it could arguably be regarded as touching upon several rights, such as the right to respect for private life (Article 8) and the right not to be discriminated against (Article 14), the concept seems far-fetched and vague.”[32]

France and Belgium also argued that the ban was necessary to enhance “gender equality” in a democratic society. In relation to this, it is pertinent to mention that in Şahin v. Turkey,[33] the ECtHR stated that,

“…banning headscarves would only protect the freedoms of those who do not wish to wear a headscarf. However, with a complete ban on the face veil, a woman may also equally be deprived from the possibility of exercising her personal freedom to wear what she chooses.”[34]

Similarly, the Conseil d’Etat acknowledged for the same reason that gender inequality was a weak justification for a complete ban on face-veils in public.[35]

Considering the discussion above, it would not be wrong to say that basing a general ban on face-veil for reasons of public safety, living together, woman’s rights and other so-called legitimate aims is very problematic. The so-called legitimate aims are also not actually legitimate. Such a ban is clearly not necessary in any democratic society in modern Europe. Prior to the enactment of laws banning face-covering, France and Belgium already had some local policing laws, municipal laws and other local regulations prohibiting the covering or concealing of the full face and as per those rules and regulations, the police was allowed to check the identity of individuals. The said local laws and regulations are still in existence and have not been repealed. They should be enough to achieve any legitimate aims.

The legality of French and Belgian bans on the wearing of clothing that hides someone’s identity in public places is highly questionable. The banning laws do not appear to be compatible with the ECHR and other international human rights commitments of France and Belgium. The banning of the full-face veil has also affected a segment of Muslim women and that is why it can be said that the laws banning the full-face veil are not neutral in relation to faith. The objectives of the ban remain ambiguous and even courts have been unsuccessful in explaining them in a convincing manner. Local laws and regulations in France and Belgium seem adequate to achieve the so-called legitimate aims, if considered legitimate at all, but even then wearing a full-face veil does not warrant criminal punishment.

References

[1] [Law 2010-1192 of Oct. 11, 2010 Banning the Concealment of the Face in the Public Space] arts. 2–4, Journal Officiel de la République Française [J.O.] [Official Gazette of France], Oct. 12, 2010, p. 1.

[2] Translation of: Wet van 1 juni 2011 tot instelling van een verbod op het dragen van kleding die het gezicht volledig dan wel grotendeels verbergt, B.S. 13 juli 2011.

[3]<https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do;jsessionid=E76497ABC2FE0C4BB1A97D27E66FB6E8.tpdjo13v_1?cidTexte=LEGITEXT000022912210&dateTexte=20131227 > accessed 11th March 2019

[4] < http://www.etaamb.be/fr/code-penal-du-08-juin-1867_n2012000627.html> accessed 11th March 2019

[5] <http://www.etaamb.be/fr/loi-du-01-juin-2011_n2011000424.html> accessed 11th March 2019

[6] (App. No. 43835/11) – [2014] ECHR 43835/11

[7] Ibid [153]-[159] (Lord Nussberger and Lord Jäderblom)

[8] Ibid [161]-[162] (Lord Nussberger and Lord Jäderblom)

[9] Supra note 6

[10] Supra note 3

[11] ibdi

[12] <https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf> accessed 18th March 2019

[13] Ireland v UK [1978] ECHR 5310/71, para 162

[14] FX Millet, ‘Case Comment: When the European Court of Human Rights Encounters the Face: A Case Note on the Burqa Ban in France’ (2015) ECL Review 11(2) 408-424, 416

[15] Supra note 6

[16](Application No. 42393/98) [2001] ECHR 15

[17] ibid

[18] Supra note 11

[19][2012] 54 EHRR 20

[20] ibid

[21] Karima Bennoune, Secularism and Human Rights: A Contextual Analysis of Headscarves, Religious Expression, and Women’s Equality Under International Law, (2007)

[22] ibid

[23] (Application 4619/12) [2017] ECHR 656

[24] (Application No 37798/13) [2017] ECHR 655

[25] < https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23750&LangID=E > accessed on 20th March 2019

[26] Evans, M., Manual on the Wearing of Religious Symbols in Public Areas (Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing) (2009)

[27] ibid

[28] <http://english.conseil-etat.fr/> accessed 21st March 2019

[29] Essex Human Rights Review Vol. 9, No. 1. June 2012

[30] supra note 17

[31] supra note 6

[32] supra note 6, [5] (Lord Nussberger and Lord Jäderblom) available at <https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/app/conversion/pdf/?library=ECHR&id=001-145466&filename=001-145466.pdf&TID=uexpxlonsk > accessed 22nd March 2019

[33] supra note 17

[34] supra note 16

[35] Conseil D’état [Counsel of State], Étude Relative Aux Possibilités Juridiques D’interdiction Du Port Du Voile Integral [Study On The Legal Possibilities Of Banning The Full Veil] (Mar. 30, 2010)

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which he might be associated.

See also: Hijab – By Choice Or By Force?