Abstract

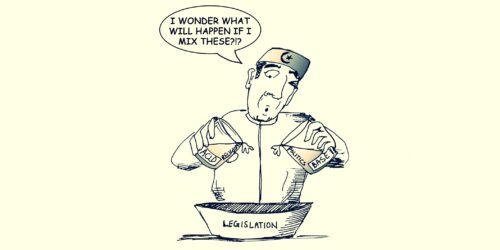

This article attempts to provide an analytical review of Pakistan’s historical and continuing experience with blasphemy law, the validity of the law on the basis of Islam and a critical analysis of the law in light of its rampant abuse. The law continues to be a cause for concern because of the patent defects in its form and procedure, exacerbated by Pakistan’s current social and political milieu. The article also highlights the procedural inadequacies of the Pakistani legal system and the very form and design of blasphemy law which tends to invite abuse. The article proposes certain recommendations and suggestions to improve the status and efficient functioning of blasphemy law if it is not to be repealed.

Introduction

Blasphemy laws, since their introduction in the 1980s by General Zia ul Haq, have oftentimes captured local and international headlines for the apparent injustice within their form and procedure, as manifested by the human tragedies that have occurred as a result of the abusive enforcement of the country’s strict blasphemy laws.[1] Blasphemy laws in Pakistan arguably exist in a more problematic and controversial form than in other countries and are therefore denounced by Pakistani civil society activists, international human rights organizations and members of the judiciary and the government who have all observed how Pakistan’s offences against religion violate its obligations under international human rights law. They have all urged for Pakistan to repeal or amend them.[2] Furthermore, the retention of the mandatory death sentence as a penalty under Section 295-C of Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) violates Pakistan’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) with respect to the right to life, fair trial and prohibition of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. It is unfortunate that the organs of the Pakistani state – the executive, the legislature and the judiciary – have effectively abdicated their responsibilities under human rights law and knowingly left the people accused of blasphemy either at the mercy of lynch mobs and organized religious groups or facing trials that are fundamentally unfair.[3]

Origins and History of Blasphemy Law in Pakistan

It was in 1860 that the British government, after making India a part of its empire, introduced and enforced the Indian Penal Code 1860 in India, which to this day has continued to be part of the criminal law in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. So the provisions regarding “offences relating to religion” date back to the IPC 1860, including Section 295 which is particularly concerned with “intentional damage or defilement of a place or object of worship”. In 1898, an important provision was included through Section 153A dealing with “offences against public tranquility” which governed the issue of promoting enmity between different groups on the grounds of religion.[4] These provisions were not in the form of strict liability offences and instead involved certain prerequisites to be fulfilled in order to undoubtedly prove one’s intention. Thus, mens rea was an important aspect of such crimes.

In 1860, the British also introduced a couple of other provisions such as s.296 (disturbing religious ceremonies or gatherings), s.297 (trespassing on places of burial) and s.298 (intentionally insulting an individual’s religious feelings), clearly indicating that the reason behind the introduction of such provisions in multicultural India, where people from different religions had been living together, was to initially maintain law and order, as avoiding conflict between different groups was considered essential to control colonized populations.[5] By introducing such provisions, the British government was aiming to establish public order, harmony and governance, thus such provisions fell within the domain of siyasah, as exemplified by the ‘Rajpal incident’ illustrated below.

A Hindu publisher, Rajpal, published a pamphlet with provocative content and had a case filed against him[6] under s.153A, sentencing him to imprisonment of 6 months and fine of 1000 rupees. His appeal against the decision only earned him a reduction in punishment, thus he challenged the decision before a Single Bench of the Lahore High Court which acquitted him on the basis that section 153A was not meant to stop polemics against a deceased religious leader ‘however scurrilous and in bad taste such attack might have been’. The Muslims rose in anger and soon Rajpal was killed. The incident eventually compelled the British government to introduce in 1927, Section 295-A in the Indian Penal Code, in which the essential requirement of mens rea was still intact and criminalized the “deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious believers, to be punishable with imprisonment of two years.”[7] The founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah also highlighted that it was of paramount importance that “…those who are engaged in historical works, in the ascertainment of truth and in bona fide and honest criticism of a religion shall be protected.“[8]

Pakistan’s Blasphemy Law During General Zia ul Haq’s Regime

Pakistan retained the Penal Code inherited from the British following Independence in 1947. There had only been 10 reported judgments between 1947-1977 with regard to offences against religion and the majority of complaints made under section 295-A had been dismissed by the courts on the basis that they had failed to meet the requirement of “deliberately and maliciously” hurting religious sentiments. Furthermore, the cases mostly involved complaints from one Muslim against another Muslim, or a non-Muslim against a Muslim, rather than from a Muslim against a non-Muslim.[9]

It was in July 1977 that General Zia ul Haq, the then Chief of Army Staff, imposed martial law in Pakistan and abrogated the Constitution. He introduced “Islamization” of laws in Pakistan, leading to major changes in the Pakistan Penal Code. Additional laws, seemingly specific to the context of Islam, had been introduced within the ambit of blasphemy as well. Out of these laws, the highly infamous and one of the most invoked provisions today is section 295-C.[10]

In 1984, the existing provisions stipulated in s.295 were challenged in a case[11] by Ismail Qureshi who contended that such provisions were repugnant to Islamic injunctions. According to him, Islamic law prescribed death as punishment for blasphemy (s.295-C), whereas the existing provision prescribed imprisonment. The case led to changes in the law, which now stipulates death as punishment, or imprisonment for life and liability to pay fine.[12]

In 1991, the law was challenged again in another case[13] by Ismail Qureshi who argued that for the offence of apostasy, death was a hadd punishment (prescribed by religion, as opposed to tazir punishment prescribed by the legislature or judiciary), therefore the same punishment should be given for committing the crime of blasphemy against any Prophet. The full bench of the Federal Shariat Court accepted the plea and directed the federal government to make the necessary changes in s.295-C, failing which would still cause the changes to take place automatically. Thus, the phrase “or imprisonment for life” in s.295-C now essentially has no legal effect and while the courts consistently impose the death penalty under s.295-C, they also do not require proof of specific intent to defame the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him) as a requisite condition to prove the offence.[14]

Islamic Basis for Blasphemy Law in Pakistan

According to theologian Ibn Taymiyyah,[15] a majority of people consider the act of blasphemy as a hadd offence punishable with the death penalty, based on a hadith,[16] however, given the seriousness of such a punishment, it is still of paramount importance that the contemnor’s explanation for his or her words or intentions is ascertained before conviction.[17]

Ibn Abidin, a prominent Islamic scholar and jurist of the Hanafi school of thought, has thoroughly explained that an alleged perpetrator of both blasphemy and apostasy can repent and that his or her repentance can be accepted. Moreover, an alleged perpetrator is not to be executed after re-entering the folds of Islam. This comes from the fact that when a Muslim blasphemes, he or she apostatizes or leaves religion, therefore the act of blasphemy can be referred to as an act of apostasy and people are allowed to return to religion by repenting the act.[18]

Pakistan’s legal system mostly follows the Hanafi school of thought. The position of Hanafis seems to be in consensus with other jurists with regard to the death penalty as punishment for blasphemy for Muslims only, and not for non-Muslims, for the reason that blasphemy by a Muslim would amount to apostasy.[19][20] The jurists believe that the act is still pardonable, though some consider apostasy to be liable to a hadd punishment and thus not pardonable or commutable, whereas others argue that death as a punishment for apostasy is only plausible if the act in question had been accompanied with the intention to continue with the infidelity. Therefore, apostasy alone will not attract the death punishment if the apostate repents and re-embraces Islam.[21] Similarly, the death penalty is not to be applicable to a non-Muslim accused of blasphemy who repents and embraces Islam.[22]

Hanafi jurists[23] regard blasphemy committed by a non-Muslim as a siyasah offence and if the convict repents, his or her repentance may be accepted and he or she may be pardoned unless deemed a potential threat to the community, but even in that situation he or she is still to be awarded punishment under the doctrine of siyasah and not as a hadd punishment.[24]

Muslim jurists regard that the legal status of an accused non-Muslim will depend on the existence and nature of the contract of peace which he or she has concluded for living within a Muslim state and without which he or she will be unable to enjoy the protection of Islamic law or have Muslim courts enforce his or her legal rights. In this regard, non-Muslims are divided into three basic categories: harbi, musta’min and dhimmi, where dhimmi refers to protected individuals living permanently in dar-ul-Islam as a result of concluding a contract of perpetual peace and having been granted special status and safety under Islamic law in exchange for paying jizya tax.

According to Hanafis, if a dhimmi makes an insulting remark about Islam or the Quran, or commits blasphemy against any of the Prophets (peace be upon them), he or she still does not, through any of these acts, terminate the contract of dhimmah. Kasani and Marghinini[25] hold a similar view with regard to the underlying principle. Therefore, the Hanafis deem the offence of blasphemy by a non-Muslim fit to be governed by tazir and thus under the doctrine of siyasah as it disturbs the peace (aman) violating the rights of the community. On the other hand, the offence of blasphemy allegedly committed by a Muslim would invoke hadd punishment for violating the right of Allah (or the Prophet as Allah’s Messenger), therefore all the standard evidentiary rules required for hadd offences must apply.

Abuse of Blasphemy Law in Pakistan

Internationally, Pakistan’s blasphemy law has been termed draconian and has made several headlines over the past few years, especially with reference to two high-ranking government officials being assassinated because of their opposition to the punishments under the law. The officials included the Minister for Minorities Affairs, Shahbaz Bhatti and the Governor of Punjab, Salman Taseer who also sought the Presidential pardon for a woman named Asia Bibi[26] who had been sentenced to death in 2014 over blasphemy allegations and sat in jail for many years waiting for an appeal.

Some of the reasons for the misuse of this law lie in the vagueness of what actually constitutes blasphemy. The language of the sections is vague and overly broad. The main ingredients of s.295-C include the following:

- whether the accused directly defiled the sacred name of the Prophet(s);

- in addition to punishing spoken and written words and “visible representations”, the statutes also punish sounds, gestures and placement of objects, along with indirect defamation, such as innuendos and insinuations.

The issue with such vagueness is that most local officials make the determination based on their own interpretation of Islam.[27]

Another objection often raised against this law is the frighteningly minimal burden of proof imposed on those accusing another of blasphemy. The issue is that the law does not require proof of intent on part of the accused, while the oral testimony of only a few prosecution witnesses is deemed admissible for the conviction of the accused, resulting in the death penalty.[28] Moreover, in many cases, the accused are often presumed guilty and the burden is put on them to prove their innocence rather than on the prosecution to prove their “guilt” beyond reasonable doubt.[29] In addition, there are no penalties for false allegations, making the law an easy tool to use to threaten anyone.[30]

With regard to the abusive use of blasphemy law against non-Muslims, the US Department of State reported a total of 1,032 people being charged under Pakistan’s blasphemy law between 1987 and 2009. Most of the cases had been initiated against Ahmadis and Christians, but also Muslims, including orthodox Sunni Muslims. According to the 2018 Annual Report of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF),[31] strict blasphemy laws in the country and increased extremist activity have further threatened the already marginalized minority communities, including the Ahmadis, Christians, Hindus, Sikhs and Shi’a Muslims. There has also been an increase in blasphemy cases being brought against Muslims[32] as compared to other faith groups, often using the threat of blasphemy to harass someone in property disputes.[33]

Another reason for this law falling into the hands of those who abuse it is that the offence under s.295-C falls under cognizable offences, whereby the police can directly register a criminal case and investigate and arrest the accused without a court order, so the possibility of charging innocent persons is greater under cognizable offences as no prior permission from a magistrate is obtained nor does a court go through the details of the case. For these reasons, allegations are often uncritically accepted by the police.[34]

Furthermore, the trial hearings of blasphemy cases also routinely fall short of Pakistan’s obligations to comply with international law, international standards on fair trial and international obligations to ensure the implementation of safeguards by the police during pre-trial detention and by trial courts during custody, which results in the violation of Articles 9 and 14 of the ICCPR. A reason for this is that the police and courts face threats and intimidation in blasphemy cases.

Section 295-C is also a non-bailable offence, which means that bail is not granted as a right but only at the discretion of the court. However, statutory rights are available to individuals who have been denied bail if their trials or appeals have not been heard within a year.[35]

The blatant misuse of blasphemy laws has created an environment in which the laws have been used as a cover for perpetrators of mob violence at the hands of which many have suffered. Many misguided people, including the complainants and their supporters, believe themselves to be entitled to take the law into their own hands, while the police merely watches from the sidelines.[36]

Considering the abuse and manipulation to which Section 295-C is subjected and the context within which it operates, there is a dire need for the introduction of certain procedural rules and changes in order to curb the misuse of this law. The use of the Qadhf Ordinance to promulgate a separate offence of ‘false accusation of blasphemy’ can be beneficial to prevent the misuse of blasphemy laws.

The existing evidentiary procedures for blasphemy laws can also be amended where a blasphemous act attracts tazir punishment. Unlike the Islamic law of evidence, tazir does not emphasize on having eye-witnesses. The procedures of evidence for tazir punishments are contained in the Qanun-e-Shahadat Order 1984.[37]

Where proof of intention is not required to prove blasphemy, it would be fair and reasonable to require accusers to provide substantial rather than circumstantial evidence against alleged blasphemers. The accuser should provide substantial proof that the act was intentional.

To further reduce the risk of abuse of these laws, such offences should be declared non-cognizable, requiring the police to be bound to refer the matter to a magistrate or court.[38]

According to a recommendation proposed by the National Commission on Human Rights (NCHR), there should be an aspect of repentance in substantive laws, in order to ensure the effective implementation of section 156A of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC).

With regard to the investigation of offences under section 295-C of PPC, the investigation process should take into account all other sections related to blasphemy law in order to decrease prosecution based on false and malicious complaints.

More awareness and training regarding blasphemy law is required for the imams, investigating officers, prosecutors, judges and lawyers.[39]

USCIRF has also recommended enacting reforms in the law to make blasphemy a bailable offence, require substantial evidence from the accusers, allow investigating authorities to dismiss baseless and unfounded accusations and criminalize perjury and false accusations.

Until the government of Pakistan repeals or reforms its blasphemy and anti-Ahmadi laws, it is encouraged to enhance the role of the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Interfaith Harmony to foster interfaith dialogue, empower religious minority groups, provide security to marginalized groups and facilitate meetings between leaders and scholars of various religions and sects.[40]

Books

-

The Holy Quran

-

Muhammad Abdul Basit, Pakistan Penal Code Act No. XLV of 1860, 2017.

-

Sahih Bukhari, Kitab al-Maghazi

-

Qazi Iyad, Al-Shifa, vol.2.

Articles/Journals

-

Osama Siddique and Zahra Hayat, Unholy Speech and Holy Laws: Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan-Controversial Origins, Design Defects, and Free Speech Implications, MJIL, Vol 17:2, 2008.

-

Amnesty International, “As Good As Dead” The Impact of The Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan, 2016.

-

Muhammad M. Ahmad, Pakistani Blasphemy Law Between Hadd and Siyasah: A Plea for Reappraisal of The Ismail Qureshi Case, 2017.

-

ICJ (International Commission of Jurists), On Trial: The Implementation of Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws, 2015.

-

Shagufta Omar, Abolition of Death Penalty with Special Reference to Pakistan, 2012.

-

Muhammad Munir, Freedom of Expression, Information, Thought and Religion in Islam and Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).

-

Asma T. Uddin, The UN Defamation of Religions Resolution and Domestic Blasphemy Laws: Creating a Culture of Impunity.

-

Urjala Akram, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion and Islam: A Review of Laws Regarding ‘Offences Relating to Religion’ in Pakistan from a Domestic and International Law Perspective, EJLR, 2015.

-

Atta Ul Mustafa, Proposed Procedural Amendments to Check Misuse of Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan, 2016.

Reports

-

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom 2018 Annual Report.

References

[1] United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, 2018 Annual Report, 70.

[2] Osama Siddique and Zahra Hayat, Unholy Speech and Holy Laws: Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan-Controversial Origins, Design Defects, and Free Speech Implications, MJIL, Vol 17:2, 2008, 305.

[3] Amnesty International, “As Good As Dead” The Impact of The Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan, 2016, 14.

[4] Muhammad M. Ahmad, Pakistani Blasphemy Law Between Hadd and Siyasah: A Plea for Reappraisal of The Ismail Qureshi Case, 2017, 10.

[5] ICJ (International Commission of Jurists), On Trial: The Implementation of Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws, 2015, 8.

[6] Rajpal v. Emperor, AIR 1927 Lah 250.

[7] Supra, at 4.

[8] Supra, at 5.

[9] Id.

[10] Amnesty International, “As Good As Dead” The Impact of The Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan, 2016, 10.

[11] Ismail Qureshi v General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Shariat Petition no. 1/L/84 of 1984.

[12] Muhammad M. Ahmad, Pakistani Blasphemy Law Between Hadd and Siyasah: A Plea for Reappraisal of The Ismail Qureshi Case, 2017, 15-17.

[13] Ismail Qureshi v The Government of Pakistan, PLD 1991 FSC 10.

[14] ICJ (International Commission of Jurists), On Trial: The Implementation of Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws, 2015, 14.

[15] “any person who curses the Prophet, invokes against him, desires to harm him ascribes to him what does not behove with his position or uses any insulting, false and unreasonable words about him or imputes ignorance to him or blames him with any human weakness, he is a contemnor.”

[16] Qazi Iyad, al-Shifa, vol.2, p.199, Tradition of Prophet goes, “Kill the person who abuses a prophet and whip the one who abuses my companions.”

[17] Shagufta Omar, Abolition of Death Penalty with Special Reference to Pakistan, 2012, 31-32.

[18] Muhammad Munir, Freedom of Expression, Information, Thought and Religion in Islam and Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), 14.

[19] The Holy Quran, Surah Al-Ahzab, Ayat 57, “Indeed, those who abuse Allah and His Messenger – Allah has cursed them in this world and the Hereafter and prepared for them a humiliating punishment.”

[20] Bukhari, Kitab al-Maghazi, Bab Hadith al-Ifk, “Allah’s Messenger said: “Who will support me to punish the person who has hurt me by slandering the reputation of my family? Saad b. Mu‘adh got up and said: “O Allah’s Messenger! By Allah, I will relieve you from him; if that man is from the tribe of the Aws, then we will chop his head off; and if he is from among our brothers, the Khazraj, then order us, and we will fulfill your order.”

[21] The Holy Quran, Surah Al-Anfal, Ayat 38, “Say to those who have disbelieved [that] if they cease, what has previously occurred will be forgiven for them. But if they return [to hostility] – then the precedent of the former [rebellious] peoples has already taken place.” and Muslim, Kitab al-Iman, Bab al-Islam Yahdimu Ma Qablahu, “Islam quashes what precedes it.”

[22] Muhammad M. Ahmad, Pakistani Blasphemy Law Between Hadd and Siyasah: A Plea for Reappraisal of The Ismail Qureshi Case, 2017, 18-32.

[23] Abu Yusuf Ya`qub b. Ibrahim al-Ansari, Kitab al-Kharaj, “Any male Muslim who commits blasphemy against the Prophet (peace be on him), or rejects his message, or ascribes any defect or shortcoming to him, renounces faith in Allah and, resultantly, his marriage to his wife stands terminated. If he repents [well and good]; otherwise, he is given death punishment. The same is the rule about a female, except that, according to Abu Hanifah, the convict will not be given death punishment, but will be forced to reembrace Islam.”

[24] Supra, at 22.

[25] “Blasphemy against the Prophet (peace be on him) is kufr; when the kufr at the time of the conclusion of the contract could not become an obstacle in its conclusion, the kufr that came into existence after the contract was concluded cannot terminate it.”

[26] Mst. Asia Bibi v. The State & another, FIR 326, Crl. App. No.2509 of 2010.

[27] Muhammad Abdul Basit, Pakistan Penal Code Act No. XLV of 1860, 2017, 383.

[28] 2005 YLR 985.

[29] PLD 2002 Lah. 587.

[30] Asma T. Uddin, The UN Defamation of Religions Resolution and Domestic Blasphemy Laws: Creating a Culture of Impunity, 9-15.

[31] United States Commission on International Religious Freedom 2018 Annual Report, 70.

[32] “According to NCJP, a total of 633 Muslims, 494 Ahmadis, 187 Christians and 21 Hindus have been accused under various provisions on offences related to religion since 1987,” Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, State of Human Rights, 2014, pp. 46-51.

[33] Supra, at 31.

[34] Urjala Akram, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion and Islam: A Review of Laws Regarding ‘Offences Relating to Religion’ in Pakistan from a Domestic and International Law Perspective, EJLR, 2015, 366-367.

[35] Amnesty International, “As Good As Dead” The Impact of The Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan, 2016, 12-13.

[36] Id.

[37] Urjala Akram, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Religion and Islam: A Review of Laws Regarding ‘Offences Relating to Religion’ in Pakistan from a Domestic and International Law Perspective, EJLR, 2015, 372-374.

[38] Id

[39] Atta Ul Mustafa, Proposed Procedural Amendments to Check Misuse of Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan, 2016, 6-7.

[40] United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, 2018 Annual Report, 64.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which she might be associated.