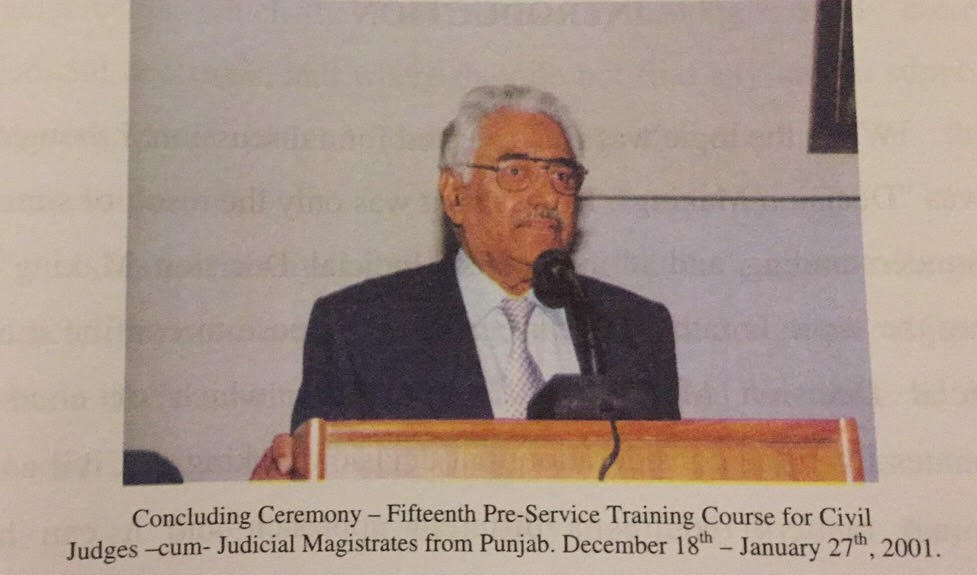

In Conversation With Mr. Hasan Nawaz Jowandah

Hasan Nawaz Jowandah graduated from the University of Punjab in 1952. After that he passed the Provincial Civil Service (Judicial Branch) Competitive Examination and served as a judicial officer in various capacities from June 1955 to 1971, including service as Additional District and Sessions Judge after promotion to senior CSP scale.

From 1973 to 1978 Jowandah sahib served as District and Sessions Judge, and from 1978 to 1988 as the Joint and Deputy Secretary Ministry of Law, Justice and Human Rights. He also served as a member of the Federal Service Tribunal from 1988 to 1994. From 2000 to 2005, he served as Director of the Federal Judicial Academy.

Mr. Jowandah has also written a book titled Systems & Situations which is a collection of essays related to law that he penned down from time to time.

Q: Why did you choose judiciary over practising as a lawyer?

“The practice was not to my liking – appearing before the court, pleading cases and moving from one place to another was difficult. For practice one must have a temperament. A lot of hassle is involved which I did not prefer. So I took the PCS examination. There were only 8 vacancies in Punjab at that time. I passed it and became one of the 45 civil judges in Punjab. I couldn’t reconcile or adjust myself by being a lawyer, so I decided to go for judiciary and succeeded. God has been very kind to me and I still take pride in representing myself as a retired judicial officer.”

Q: What do you think are the serious problems faced by courts in big and small cases?

“After years of experience as trial judge, I strongly believe that inefficient criminal investigation and public prosecution causes the most problems in the dispensation of justice within the criminal justice system. Competent criminal investigations are obviously of great importance for an efficient administration. Those who conduct them should be highly educated and trained. The principal difficulty is generated by the mix of police duties since they are involved in crime prevention and control and conducting criminal investigation. It is difficult for the officers to perform both classes of functions with equal skill. The only effective solution to the problem lies in the separation of these two functions through the creation of special agencies which do nothing apart from conducting criminal investigations, leaving maintenance of public security and order to the regular police.

The Second problem faced by the courts is related to public prosecutors. Criminal cases tried in courts of sessions are prosecuted by the prosecuting officer if they have been initiated through the police report. The Code allows a prosecuting officer to withdraw a prosecution, with consent of the court, before pronouncement of the final judgment. In that event, a defendant is either discharged or acquitted, depending on the stage of the proceeding reached when prosecution is withdrawn. A police officer in a magistrate’s court has similar powers. The processes of investigation and prosecution are exclusively under the control of executive authorities which, most of the time, get influenced by officers and political interferences, coupled with inefficiencies in collecting evidence, and cause a low rate of convictions. Public prosecutors should be members of the legal profession and have passed a national bar examination.”

Q: Is there any case which stands out for you, from your time at court serving as a judge?

“During my time as a judge in Bahawalpur, there was a person named Allama Arshad, who had been elected to the Provincial Assembly and was also the Leader of the Opposition. His brother was contesting the election for Bahawalpur Municipal Corporation but his opponent filed a case against him demanding the rejection of his candidature because in waldiyat (parentage/guardianship) his brother’s name was listed instead of father’s name. I faced this case in a very crowded courtroom. According to me there should have been no conflict or dispute over such a thing since there was no one with that name in that district. I kept standing on my feet in the courtroom till late night and then dictated my judgment. I knew if I would delay the judgment even for a day people would say that the decision wasn’t mine and that it was influenced by the District Commissioner.”

Q: You have written about delays in the disposal of cases and the problems faced by courts in criminal and civil litigation, where a presiding officer may have to deal with a cause list of 120 to 150 cases in one working day. How do you think the court’s time should be split between the criminal and civil calendar? What would eventually help in saving the court’s time and reducing delays in the disposal of cases?

“Case Management or Prioritization Committees should be formed, constituted by the District and Sessions Judges in each district, including the Presiding Officer of the concerned court as Chair, Reader of the court, representatives of stakeholders and their counsel as members. There should be category-wise prioritization of cases:

In civil matters with reference to and on the basis of:

- nature of the case,

- dates of initiation of proceedings,

- location and value of the property in dispute,

- civil rights involved,

- the parties,

- impact of the ultimate decision

- the number of the persons affected by the decision of the court,

- involvement of public interest,

- the nature of questions involved for determination,

- whether any temporary injunction has been granted in favor of either of the parties, and

- other relevant considerations.

In criminal cases, priority can be determined on the basis of:

- dates of initiation of proceedings,

- nature and gravity of the offence,

- the number of the persons involved,

- the number of persons involved and affected,

- public interest in the outcome,

- impact of the judgment to be passed in the case, and

- maximum punishment provided for a particular offence.

After the process of prioritization gets completed, the Presiding Officer may put 500 cases, in order of priority, on the active calendar for trial and final disposal.”

Q: How did you assess the quality of advocacy in your courtroom?

“In civil cases, the evidence presented in the court is mostly documentary evidence, so on the civil side the advocacy of a lawyer is assessed by how much knowledge of law he or she has. On the other hand, in criminal cases, there is more reliance on oral advocacy, so it is judged by the arguments presented by the lawyer, though we used to get annoyed by lawyers who used to drag their arguments just to satisfy their clients.”

Q: What is one thing you would change about procedural law if you could?

“Criminal and Civil Procedure law has stood the test of time and therefore doesn’t need to be amended. The problem is not with procedural law, the problem is with arguments, character and the taking of bribes by lawyers, witnesses and judges. The problem is in the system.”

Q: What effect do you think political polarization has on the judiciary?

“I was attending a conference once in Nova Scotia, where a representative from Philippines asked whether we should address political questions in court. In my opinion, the political question should not be asked in court, it wastes the time of the court and can influence the judges too, due to which people have lost faith in the judiciary.”

Q: What is the most important thing you want people to know about the courts and the judiciary?

“Litigants should rely on the court, even though strikes by lawyers and the Bar make it hard. Also, people should respect the judgment of the court and the court should also make itself worthy of the respect.”

Q: Any message you want to give to the young aspiring judges?

“Read as much as you can, be conversant with the laws and judgments of landmark cases, be honest and be known for your honesty.”

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which she or he might be associated.