Pak-Turk Schools Case and Proposals for Regulating Supreme Court’s Powers Under A.184(3)

[Download the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Pak-Turk Schools case here: SC Judgment – Pak Turk Schools]

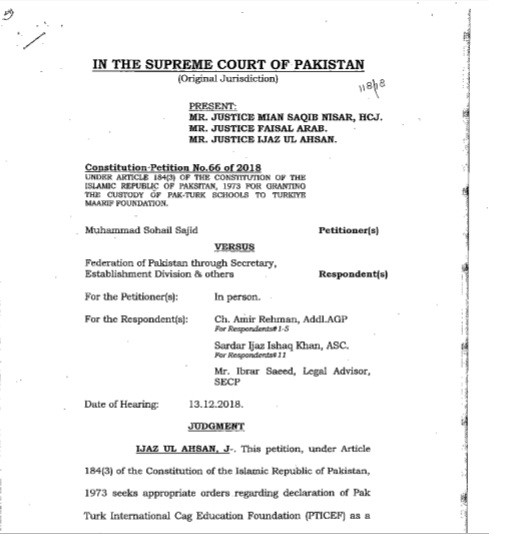

On the 13th of December, 2018, electronic media reported a very unusual decision announced by the Supreme Court of Pakistan. Acting as a court of first instance, the Court decided to declare the management of Pak-Turk Schools – comprising mostly Pakistani businesspersons and teachers – a “terrorist organization”. The Court also dissolved the registered non-profit company which owned 28 schools worth billions of rupees and handed these assets over to another non-profit, the Ma’arif Foundation, fully controlled by the Turkish government. The decision was made after the first and last hearing of a case titled Sohail Sajid v. Federation of Pakistan and others (Constitution Petition No. 66/2018).

This was a case of judicial overreach par excellence. However, since it was only one in a long series of such cases, news of it faded into oblivion after making a few headlines. The case briefly resurfaced on the morning of 27th December, 2018 – which is when I first read about it. I think it is telling that despite the historic significance of this judgment, only one newspaper, the Express Tribune, bothered to report its contents in any considerable detail.[1] People may have been mummed because in 2018 not a day had passed without the Supreme Court giving a raw deal to elected parliamentarians, senior civil servants, expert lawyers, eminent journalists and leading private entrepreneurs. In December 2018, a time had come when the Supreme Court committing excesses while exercising its original jurisdiction was no longer news.

But this case is worth exploring because it represents something new. At the receiving end was a group of virtually powerless people: teachers. The court did not simply chide them, it went all the way and declared them a terrorist organization. Neither was I counsel for any of the parties involved nor did I have any professional ties to them. In fact, I only learnt about this case through the news story which I read on 27th December, 2018. I decided to write about it simply because the facts can help sensitize us about what is wrong with the present practice of Article 184(3) of the Constitution and what can still be done to fix it. The account which I present here is based on my independent review of the entire case-file as well as interviews with parties on both sides of this dispute. In the wake of Chief Justice Asif Saeed Khosa’s welcome call for reinterpreting Article 184(3), this case is especially worth probing into.

The Pak-Turk Schools

The Pak-Turk Schools is a chain of schools set up over the last two decades by a network of educators who were inspired by a Turkish religious figure known to his followers as Ustaad Fethullah Gulen.

Gulen’s followers did not set up schools in Pakistan only; they set up hundreds of schools in dozens of countries around the world. It is important to remember that although the schools were set up by Gulen’s followers, they were never owned by Gulen. They were not even owned by his followers. They were set up, in each country of the world, as registered “foundations”, or “auqaf” as they are more widely known in the Muslim world.

In Pakistan, the schools were initially set up and owned by Pak-Turk International CAG Education Foundation (PTICEF), an NGO registered in Turkey under Turkish law. Back in 1997, PTICEF, like other international NGOs operating in the country, obtained a licence from the Economic Affairs Division of the Government of Pakistan. However, by 2014, the schools had been legally handed over by PTICEF to Pak-Turk Education Foundation (PTEF), a non-profit registered in Pakistan, under Pakistani law. As a result of this corporate restructuring, by the time the 2016 coup took place, the schools were totally independent of Turkey and were governed entirely by the laws of Pakistan.

The Turkish Government’s war against the Gulen Movement

Ustaad Fethullah Gulen was once friends with the leadership of AKP, the political party which has consistently held the reins of power in Turkey for the last fifteen years. In fact, many would say that without its symbiotic relationship with the Gulen Movement, AKP would never have succeeded in gaining total control over the institutions of the Turkish state. But with time, as is the case with so many relations between people in power, the relationship turned sour. In 2016, things came to a climax when some of Gulen’s followers allegedly tried to bring about a violent coup to dethrone the AKP. The coup failed and the Turkish government headed by President Erdogan hit back at Gulen’s followers with brutal reprisals.

It was in the wake of this coup that President Erdogan coined the term ‘Fethullah Terrorist Organization’ (FETO) to describe the very loosely connected network of enterprises set up by members of the Gulen Movement. To this day, Gulen denies any involvement in the coup and denounces any effort to dethrone governments through the use of violence. But this has not helped cool Erdogan. Like many absolutist rulers before him, Erdogan seems to have become paranoid. He is consumed by the largely imaginary threat he faces from Gulen Movement supporters. As a result, hundreds of Turkish citizens have ended up getting killed, tens of thousands have been jailed, more than a hundred thousand have been fired from work or otherwise punished for the crimes of the alleged FETO. While we will never know exactly how many have suffered, much has been done by the Turkish government that cannot be called fair by any standard.

The Turkish government’s witch-hunt against Gulen’s followers also has a global dimension. Erdogan has personally reached out to all countries of the world where Gulen’s followers have any presence. Amongst them is Pakistan.

Executive versus Judiciary

From August 2016 onwards, the Turkish government has made multiple attempts to convince its Pakistani counterparts to launch a crackdown against the teachers and manager of Pak-Turk Schools because many of them are, or have at some stages of their lives been Gulen followers. Although there is not a shred of evidence that the Pak-Turk Schools ever propagated violence, extremism or terrorism in Pakistan, or elsewhere in the world, the Pakistani government has made efforts to oblige the Turkish government. In 2016, the visas of Turkish teachers were cancelled, the Counter-Terrorism Department (CTD) of Punjab Police was unleashed on them, one of them was subjected to an “enforced disappearance” and the government even tried to expropriate assets of the schools.

But for over two years, the witch-hunt had been stalled by the Pakistani judiciary. At critical moments, the High Courts of Pakistan stepped in to ensure that as long as the schools continued to comply with the laws of Pakistan, they were left unhurt.

So, for instance, on 6th December, 2016, the Chair of Pak-Turk Foundation, Mr. Alamgir Khan filed a writ petition in the Islamabad High Court (W.P. 4489-2016) urging the court to restrain the government “from interfering into the affairs of the Foundation … and from abusing public authority vested in them to execute a hostile takeover of the Foundation…” The petition also urged the court to restrain the government “from arresting or abducting the petitioner or falsely implicating him in terrorism related inquiry and restrain the said respondents from harassing the petitioner and coercing him and other members/directors of the Foundation from resigning from such positions…” In response to this petition, the High Court granted a stay order which continued to hold force until 5th March, 2018 when the petition was finally disposed based on assurances by the CTD that it had no intention to investigate the school management for terrorism charges. The court also issued directions to the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) to ensure that they “observe all legal formalities in accordance with law.”

The Turkish teachers, whose visas had been cancelled, approached the High Court of Sindh[2], the Peshawar High Court[3] and the Islamabad High Court.[4] These people, spread all over Pakistan, who had invested many years of their professional lives teaching Pakistan’s children, argued that they were being expelled by the Pakistani government for reasons that had nothing to do with their conduct in Pakistan or with the interests of the people of this country. Even though judicial precedent in Pakistan has been largely unhelpful to the cause of those seeking judicial review of visa decisions, the High Courts granted at least some relief to the Turkish teachers, protecting them from the wrath of the governments of Pakistan and Turkey.

From late 2016 to December 5, 2018, we saw the system functioning the way it was designed to function. The executive arm of the state was focused on meeting Pakistan’s foreign policy imperatives and the judicial arm was equally focused on defending fundamental rights of all persons. When it came to the Pak-Turk Schools, our judiciary literally became a bastion of civil liberties. As a citizen and practising lawyer, I felt pride in this aspect of our judicial system which displayed a commitment to the ideals of rule of law and constitutionalism.

But everything changed with the advent of Constitution Petition No. 66 of 2018 in the Supreme Court of Pakistan.

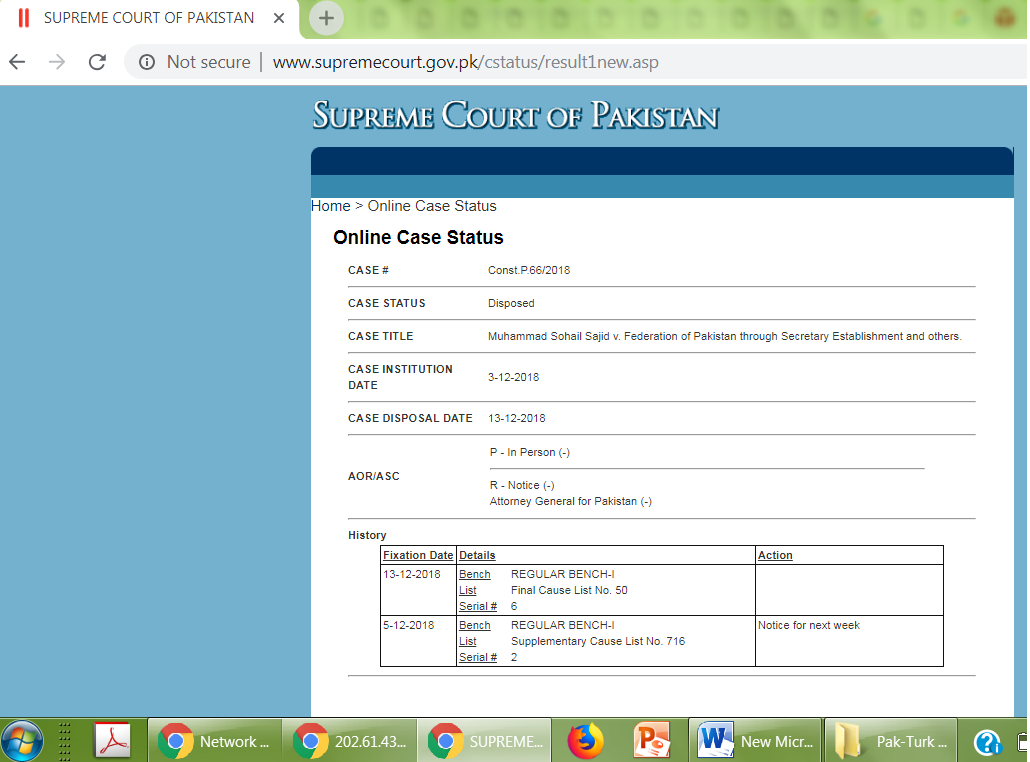

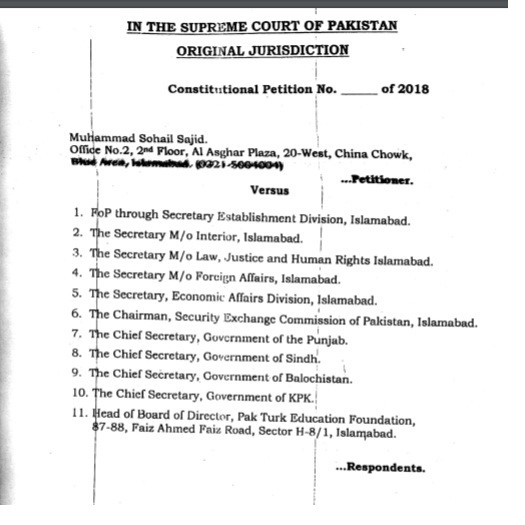

According to the record obtained from the Supreme Court’s official website, it was on Monday, 3rd December, 2018, that one Muhammad Sohail Sajid “instituted” this application in the Supreme Court under Article 184(3) of the Constitution. The record further shows that the petition was fixed for hearing on Wednesday, 5th December, 2018.

This was the prayer sought in the application:

“The Federal Government having enough reasons at the local and international level, may be directed to declare the FETO as a proscribed organization and to list it in the [F]irst Schedule according to the Section 11-B of the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997, in the best interest of the public at large…

That in the light of understanding during the highest official meetings between the two governments held on 16.11.2016 and 22.02.2017, the Honourable Court may be pleased to declare the registration of company opposed to the national interest, security and integrity of Pakistan.

It is further requested that the Federal Government be directed to take over management of Turkish schools and subsequent handover it over to the Turkiye MAARIF Foundation in the best interest of Brother Muslim States.”

(Emphasis added)

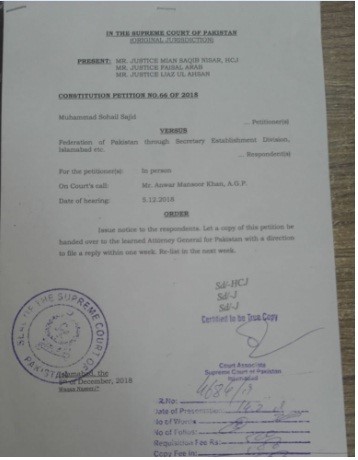

On 5th December, 2018, the court admitted the petition for hearing and instructed its staff to issue notices to the school management and to various government-related respondents for the next date of hearing which was only one week later. There was no media coverage of this hearing. The court’s own record of the proceedings (known as the “order sheet” in legal terms) is unusually brief and makes no mention of any arguments made by the petitioner. It does, however, mention that even at this preliminary hearing, the court considered it sufficiently urgent to hand over a copy of the petition straight to the Attorney General of Pakistan, the head of government lawyers.

The school management asserts that it received no notice of the proceedings against it until the evening of 11th December, 2018. On 12th December, 2018, just one day before the first hearing, the management engaged the services of Sardar Ejaz Ishaq Khan, an Islamabad-based lawyer. Quite obviously, Sardar Ejaz, who was engaged less than 24 hours before the hearing, was not able to submit a written reply to such an onerous, high-stakes petition. Therefore, he decided to appear in court only for the purposes of obtaining time to file a reply. On any other regular day, this would have been easy.

But it seems that according to the Chief Justice’s bench, Thursday, 13th December, 2018 was not a regular day. Early that morning, the case was called for hearing.[5] Besides the Chief Justice, the bench included the Honourable Justice Ijaz-ul-Ahsan and the Honourable Justice Faisal Arab. Sardar Ejaz stepped up to the podium.

When he informed the Court that he was appearing on behalf of the Pak-Turk Schools, the judges seemed to be irked. Sardar Ejaz sought time to file a reply. The Chief Justice remarked that the Court was not interested in listening to either him or the point of view of the school’s management. His Lordship stated that the documents provided by the petitioner were sufficient and the court had decided to announce a judgment on their basis.

From the very beginning, it was clear to all those present that the 3-member bench was in a hurry to give a judgment. And then, less than 3 minutes into this hearing, even before Sardar Ejaz could launch any vociferous protest, the court decided to dictate its judgment in Constitution Petition No. 66/2018, which was as follows:

“(i) All the moveable and immoveable assets of PTICEF and its schools, colleges, tuition centers and other similar entities shall stand vested in TMF with immediate effect.

(ii) The management and financial control of such schools/institutions shall vest in and shall be exercise in accordance with decisions made in meetings between officials of Government of Pakistan and Government of Turkey held on 16.11.2016 and 22.02.2017. The Law enforcement Agencies, including FIA and Police, are directed to provide full support and assistance to representatives of TMF to take over management and control of the 28 Schools set up by PTICEF.

(iii) The Ministry of Interior shall declare PTICEF as a proscribed organization. Its name shall be included in the First Schedule of Section 11-B of the Anti-Terrorism Act, 1997.

(iv) All account in the name of PTICEF and/or any of its Directors, Administrators, employees etc., wherever held in Pakistan, shall immediately be blocked/frozen. No transaction or transfer of funds from the said accounts shall be allowed. The Ministry of Finance shall take up the matter with the State Bank of Pakistan in order to take all necessary steps and issue directions to give custody of accounts and funds held therein to duly authorized representatives of TMF which shall be deemed to have stepped into the shoes of PTIFCEF, with full powers to operate the accounts and use available funds solely for educational activities and administrative needs of the schools.

(v) Direction is issued to the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) to declare the Section 42 company created by PTICEF as defunct on account of its illegal an unauthorized initial registration and its affiliation with a terrorist organization, and remove its name from the registers of SECP.”

Between Oral Order and Detailed Judgment

The court orally announced its verdict in Constitution Petition No. 66 of 2018 at the end of the hearing on 13th December, 2018– the first hearing of the case and also its last. News of the judgment became public and the government immediately started enforcing it by taking over the schools. However, the detailed, written judgment was not available to its affectees until 27th December, 2018. The only detailed news story about the judgment ever to appear that day was a story by Hasnat Mehmood, the inveterate Supreme Court correspondent for Express Tribune.

Before we proceed to discuss the legal merits of the judgment, it is essential to mention another development that had taken place between 13th December, 2018 and 27th December, 2018 and which the affectees of the judgment must have observed with a keen eye.

On 18th December, 2018, less than five days after Chief Justice Saqib Nisar had announced the court’s decision in Constitution Petition No. 66 of 2018, there emerged a picture of His Lordship shaking hands with President Erdogan. This news was confirmed by an official press release issued by the Supreme Court of Pakistan. The press release suggested that meeting President Erdogan was not the main purpose of the Chief Justice’s tour of Turkey; he went there upon the invitation of the President of the Constitutional Court of Turkey. The meeting with Erdogan was something of a bonus.

But affectees of the court’s decision must have seen things differently. They must have wondered whether this meeting had something to do with the court’s unusually rushed decision on 13th December, 2018. After all, President Erdogan’s government was the ultimate beneficiary of the decision against Pak-Turk Schools.

The Detailed Judgment

Soon after the Chief Justice’s return from Turkey, the detailed judgment came out. It was signed by all three members of the bench and had been authored by the Honourable Justice Ijaz-ul-Ahsan.

We may now proceed to examining the legal basis and implications of the court’s ruling.

The Unanswered Threshold Questions

(i) Establishing Jurisdiction

In most countries, apex courts only decide appeals arising from other courts. The Supreme Court of Pakistan is one of the very few apex courts in the world – along with the Indian Supreme Court and the German Constitutional Court – that are entitled under the law to exercise “original jurisdiction” i.e. to take up fresh cases. The court derives this power from Article 184(3) which states the following:

“(3) Without prejudice to the provisions of Article 199, the Supreme Court shall, if it considers that a question of public importance with reference to the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights conferred by Chapter I of Part II is involved have the power to make an order of the nature mentioned in the said Article.”

While there is no denying that the Supreme Court can exercise original jurisdiction, the most serious students of constitutional law agree that this jurisdiction should be exercised very rarely. Generally, cases are not supposed to start at the apex court level. They are supposed to start at the bottom of the judicial hierarchy and then fly upwards. Therefore, in a judgment under Article 184(3), the first question, and perhaps the most difficult one, is that of establishing the court’s jurisdiction.

With this consideration in mind, let us look at the surprisingly brief explanation offered by the court for exercising its extraordinary original jurisdiction:

“The questions raised are clearly of Public importance, involve setting up and running of educations institutions, which is a fundamental right. Further citizens of Pakistan have a right to security of person and a right to education in lawfully set up educational institutions. The citizens of Pakistan also have a right and interest in the enforcement of laws to ensure that no terrorist organization or any entity, having links or nexus with such organization, is allowed to operate in Pakistan.”

(ii) Locus Standi, Bona Fides and Absence of Alternative Remedy

Judges of constitutional courts across the common law world generally sift cases through at least three filters before looking at their legal merits: ‘locus standi’, ‘bona fides’ and ‘absence of alternative remedy’. While these are all highly nuanced doctrines developed over centuries by English courts exercising the royal prerogative of issuing writs, at their core is plain common sense.

The test of locus standi places upon a petitioner the duty to satisfy the court that he or she has real stakes in the case and is not, for instance, a hired front-person or fame-hungry vigilante. The test of bona fides requires the petitioner to satisfy the court that he or she has come to the court with “clean hands”. The idea is to protect the court from becoming a tool in the hands of devious, experienced litigants trying to oppress their foes though the use of the court process. The test of ‘absence of alternative remedy’ places upon the petitioner the duty to demonstrate that the relief being sought from the court could not have been sought from a forum lower in the hierarchy. Behind this test is a principle of common sense that the judicial system should have a pyramidal structure, with only those few, legally tricky disputes reaching the top which cannot be resolved at the bottom. This test also ensures that the right to appeal of defendants is protected as much as possible.

Surprisingly, there is nothing in this very significant, high-stakes judgment about any of these questions. Neither the petition, nor the judgment, tells us anything about who the petitioners were and how they were aggrieved by the activities of the Pak-Turk Foundation. The most the petitioner said in his petition was that he was seeking relief from the Supreme Court because “being citizen of Pakistan [I] have fundamental right to live a peaceful life.” This brief line did not answer the real question which begged an answer as to why the petitioner, the only one amongst all the people of Pakistan, stepped forth to file such a petition. Come to think of it, if handing over Pak-Turk Schools to the Turkiye Ma’arif Foundation was necessary for securing the fundamental rights of all of us, why did Turkiye Ma’arif Foundation itself not step forth and file the petition? In fact, the petition did not even implead Turkiye Ma’arif Foundation as a respondent, yet the court felt confident in handing the schools over to it.

The judgment also stated nothing about how the court assured itself that the petitioner did not have any beneficial affiliation with the Turkish government or its subsidiary, the Turkiye Ma’arif Foundation. Could he not be a front-man? There was nothing in the judgment to help rule out the possibility that the petition was part of some ‘covert operation’.

There was also no discussion whatsoever about the possible alternative remedies which the petitioner could have, and should have, availed before coming to the Supreme Court. Why didn’t the petitioner ever approach the federal government or the SECP or file a writ in any of the High Courts? If the Supreme Court had allowed the lawyer for Pak-Turk Schools a chance to present his case, he would have informed the Court that the issues raised in the petition were, and still are, sub judice in various High Courts of the country. Because of the judgment, all of these proceedings have become futile. Even a quick web search – like the one I conducted for writing this article – would have made this aspect of the case clearer.

To be honest, while the short shrift given to the threshold questions in this judgment is objectionable, it is not unique. There have been many cases in recent years where the Supreme Court did not seem to waste its breath on providing legally tenable answers to such threshold questions while entertaining petitions under Article 184(3). This is not a coincidence or casual lapse. It is the ultimate culmination of a trend which can be traced back to a series of Supreme Court cases from the late 1980s, which I will discuss later in this article. For now, it is sufficient to note that the Pak-Turk Schools judgment, as ominous as it looks, is only a manifestation of a general practice.

Analysis of the Merits of the Case

After the above-mentioned response to questions of threshold, the Court proceeded to decide the merits of the case. Judgments of the Supreme Court of Pakistan often provide elegant samples of legal reasoning, which humble lawyers like me learn from, but in this case, I believe the court may have been in a rush. The discussion spans about 15 double-spaced pages but it is impossible to put together exactly what the court’s logic is.

If we read the judgment with a sympathetic eye and try to reconstruct the court’s logic in our own words, it seems that there are two distinct arguments made by the court: the terrorism argument and the foreign policy argument.

The Terrorism Argument

There were four steps of reasoning which led the Court to conclude that the management of Pak-Turk Schools was liable to be declared as a ‘proscribed organization’ under the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997, or, in simple words, a terrorist organization. As shall be evident to anyone with legal training, there are major flaws in all four steps of the reasoning.

As the first step, the court concluded that an organization called FETO existed all over the word as well as in Pakistan and was responsible for orchestrating the military coup in Turkey. Such a fact had been established by simply referring to the documents annexed with the petition.

“We are in no manner of doubt that the Government of Pakistan has international obligations towards the Government of Turkey to declare FETO as a terrorist organization and take appropriate steps to take over assets held by entities controlled by it…”

(para 19)

A perusal of the documents actually shows that the evidence is by no means conclusive. It is certainly not so conclusive that it would allow the Supreme Court to ignore the presumption of “innocent until proven guilty in a court of law”.

As the second step, the court accepted the bald allegation that all over the world PTICEF was acting only as a facade for FETO and was engaged in laundering money to FETO.

“19.There are serious allegations that the schools set up by PTICEF were a façade behind which illegal activities were taking place including money laundering and generation and transfer of funds to the parent organization, namely FETO…”

This conclusion is based entirely upon a judgment passed by a Turkish court. However, a perusal of the Turkish judgment shows that it is entirely lacking in evidence and, moreover, is confined to the Turkish context. There is not a shred of evidence in the Turkish judgment to support the allegation that Pak-Turk Schools in Pakistan were sending money to support the coup in Turkey. Also, simply asserting that PTICEF had been declared a terrorist organization in Turkey was not sufficient to establish that PTICEF was also liable to be declared a terrorist organization under Pakistani law. It is true that section 11B of the Anti-terrorism Act 1997 confers rather broad powers upon the federal government to declare any organization a terrorist organization, but section 11B, or any other law for that matter, does not require Pakistani authorities to rubber-stamp decisions of other countries, especially those decisions which have a major impact on the rights of Pakistani citizens. Therefore, the very premise that PTICEF is a terrorist organization for the purposes of Pakistan law is shaky.

The third step in reasoning, not articulated in the judgment but inferred, was that the court had concluded PTEF, the company registered in Pakistan which owned the schools in Pakistan, to only be a ‘front’ for PTICEF, the trust registered in Turkey.

“PTICEF has deceptively registered itself as a company with the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP)…”

At first glance, this might look like a case of piercing the corporate veil, a tactic which would be unfair in the circumstances, but would at least be comprehensible. However, it’s not even that. Even if you pierce the corporate veil of PTEF, you can only go after its directors. PTICEF is not one of the directors of PTEF. In fact, at the time the court made its decision, there were no common directors between PTEF and PTICEF. Essentially, the court had just drawn this conclusion out of thin air.

The fourth step in reasoning, which followed from the earlier steps, was that PTEF was liable to be declared a terrorist organization for the purposes of Pakistani law. To sum up the assertion, here’s the equation drawn by the Supreme Court, based simply upon the petitioner’s allegation and without bothering to go into any form of trial:

Coup-makers in Turkey = FETO = PTICEF = terrorist organization under ATA = PTEF

The errors in this entire chain of reasoning are many and evidence supporting them is little.

The Foreign Policy Argument

The truth is that if we are looking for the real “rationale” behind this judgment, we will probably not find it in the court’s discussion on terrorism and related charges. The terrorism argument was perhaps only a supporting argument, a filler. The real rationale of this judgment is to be found in the statements the court has made about Pakistan’s foreign policy. The following passages from the judgment make this aspect clear:

“It appears that that is complete consensus and harmony in the views of the Government of Pakistan and Turkey in this matter…

[T]o preserve and strengthen fraternal relations among Muslim countries based on Islamic unity,…” is a constitutional obligation of the Government of Pakistan.

It is fundamentally important to ensure brotherly relations between Pakistan and Turkey who have enjoyed very and fraternal relations from the day Pakistan was created…

It is therefore imperative that no steps are taken that may imperil such a relations or cause any manner of doubt in the minds of the Turkish people or their Government about the unqualified and conditional support that the Government and the people of Pakistan wish to extend in their struggle against all forms of terrorism in Turkey.”

These passages make it clear that even in the court’s mind, the real reason for handing over Pak-Turk Schools to the Turkish government-controlled Ma’arif Foundation was not the threat of “terrorism”. The real objective was to mend Pakistan’s relationship with Turkey which was being hurt by the above-mentioned stay orders issued by Pakistani courts. The only legal provision cited by the court in support of the ‘foreign policy argument’ is Article 40 of the Constitution:

“The State shall endeavour to preserve and strengthen fraternal relations among Muslim countries based on Islamic unity, support the common interests of the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America, promote international peace and security, foster goodwill and friendly relations among all nations and encourage the settlement of international disputes by peaceful means.”

Critics of the judgment must take stock of the fact that regardless of its legal defects, the judgment has, in fact, succeeded in meeting its short-term stated objective. Pakistan’s state-to-state ties with Turkey have actually improved since the judgment. Just one week after the written judgment came out, on January 4, 2019, Prime Minister Imran Khan was able to start his first official tour of Turkey after getting elected. The tour was concluded with a joint press conference and a joint declaration. There is even a line in the declaration which makes a subtle reference to the Supreme Court’s contribution in this diplomatic endeavor and underlines the abiding commitment of both countries “for fighting the menace of terrorism in all its forms and manifestations and reiterated their resolve to fight against the Fethullah Gulen Terrorist Organisation (FETO).”

Now, we may turn to the legal merits and consequences of the ‘foreign policy argument’.

The only provision of law cited by the court in support of this argument is Article 40, which is part of a chapter of the Constitution titled “Principles of Policy”. In the past, the Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected petitions seeking enforcement of these provisions of the Constitution, holding that these provisions are not meant to be enforced by the courts. This is on account of Article 30(2) of the Constitution which states that, “The validity of an action or of a law shall not be called in question on the ground that it is not in accordance with the Principles of Policy, and no action shall lie against the State or any organ or authority of the State or any person on such ground.”

Even if we concede, for a moment, that Article 40 can be enforced by the courts, surely it cannot trump the rest of the provisions of the Constitution, especially the fundamental rights guaranteed in Articles 9 to 28 to all Pakistani citizens and persons present in Pakistan. These include, amongst others, the right to a fair trial (Article 10A) and the right to security of property (Article 24). I find it deeply disturbing that the Supreme Court of our country felt comfortable in declaring a Pakistani company a terrorist organization and handed over its property to someone else, for the stated object of currying favor with a foreign ruler – and that too without affording the accused a trial. At the very least, it represents a total reversal of roles assigned in the Constitution to the executive and the judiciary. Yet, it was exactly what happened in the Pak-Turk Schools case.

Just try to imagine what the school management must have felt on the morning of 13th December, 2018. The institution of the judiciary, which had hitherto been their last of place of refuge from state authoritarianism, had suddenly changed colours. It had now become their executioner, proceeding with suo moto actions. It must have felt like a calamity.

Imran Khan’s government is probably feeling grateful to the Supreme Court for helping it out of a tricky diplomatic impasse – an impasse created partly by the stay orders issued by the High Courts while performing their constitutional duty. Little does the government realize that through the Pak-Turk Schools judgment, the judiciary may have carved out for itself a permanent role in the arena of foreign policy. Nothing now stops the courts from issuing further writs of mandamus to the government on the basis of Article 40 read with Section 11B of ATA and Section 42 of the Companies Act. As we have seen during last few years, judges tend to have plenty of ideas to offer the government. They now have a precedent allowing them to issue direction about how the government can best fulfill its constitutional obligation to “promote international peace and security, foster goodwill and friendly relations among all nations …”

A court can, for instance, direct the government to declare the Falah-e-Insaniyat Foundation a terrorist organization and to hand over its assets to a government-controlled NGO, because its parent organization, Jama’at-ul-Da’wah, has been declared a terrorist organization by the United Nations. Or, for that matter, why not direct the government to prosecute Maulana Masood Azhar for his alleged role in the Pulwama incident? Isn’t he such a thorn in our relationship with India? There is now nothing standing between the judiciary and foreign policy. Just like Article 58(2)(b) and Article 63 before it, the implications of this great gem (Article 40) in the judicial treasure-trove will unfold in due time.

There are two other aspects of this case which are worth mentioning, before we proceed to general proposals for reform.

A “Hearing” That Never Happened

There are numerous passages in the judgment which convey the impression that the decision came at the end of some closely-fought, well-argued, lengthy court proceedings. See, for instance, the following statements:

“13. Sardar Ijaz Ishaq Khan, learned ASC has appeared on behalf of PTICEF…

14. The learned counsel appearing on behalf of PTICEF has vehemently opposed this petition. He maintains that Respondent No. 11 is not a terrorist organization nor does it have any connection with any such organization. The allegations are politically motivated and there is no evidence on record linking PTICEF with FETO or CEC. He submits that just on the basis of a decision taken by the Turkish Government, no action can be taken against PTICEF which in any event enjoys independent registration with SECP as a Section 42 company…

15. We have heard the learned counsel for the parties…

16. As far as the arguments of the learned counsel for Respondent No. 11 are concerned, we are not persuaded by the same. He has not placed any document on record to that may substantiate his pleas…”

During my investigation into this case, I discovered that the lawyer for Pak-Turk Schools never made the arguments attributed to him because he was never given the opportunity. In fact, the hearings of this case were so perfunctory that there was hardly any argumentation in the courtroom from any side. The courtroom debate depicted in the judgment is a debate which was ‘staged’ subsequently. The question which arises is: why did the court– the most powerful court in the country – find it necessary to preface its judgment with staged arguments? Why bother? The answer has to do with the rather peculiar customary format for writing judgments in our legal tradition.

As lawyers, we hardly ever pause to reflect on why judgments in our legal system are always written in the particular format which may be called the ‘adversarial format’. In this format, a judge generally starts his or her judgment with a rather detailed narration of the reasoning provided by lawyers appearing from both sides. Usually, this narration takes up more than half of the entire space. It is only near the end that the judge provides his or her own reasoning which is limited to justifying why he or she chose one of the two pre-designed legal positions offered by lawyers. This format is not expressly prescribed anywhere in our law. Yet judges generally adhere to it by way of convention.

In the early years of my legal training, I used to think it was a sheer waste of time and energy, an anachronism like the wigs worn by the English judges and barristers. I know many other lawyers and even judges who don’t think much of this format. But with time and bitter experience, I have come to realize that there is great wisdom in this ‘adversarial’ format of judgment writing. It is part of a larger system of checks upon state power.

If we freed judges from this format and allowed to them chalk out legal theories in the solitude of their chambers, there are at least two dangers that would arise. First, with no one out there to point it out for them, judges would be prone to making sincere errors of reasoning; when a lawyer makes that sort of an error, the opposing lawyer has both the incentive and the opportunity to call it out. Secondly, judges, who are state functionaries, would be able to enjoy greater ‘discursive’ power which, at present, they must perforce share with lawyers appearing from both sides. The occasional abstract lectures which some of our judges have now started delivering in their judgments are a direct result of the violation of this convention.

There are, however, subtler ways in which judges are able to defeat the objectives of this rather restrictive format, while still retaining its form. This is when they put arguments into the mouth of the lawyers representing opposing parties when no such arguments have otherwise been made in court. And after putting these arguments in the mouth of lawyers, judges refute those arguments. That’s what you see happening in the judgment at hand. If you have ever been a debater, you would know how powerful a rhetorical strategy this can be. There can be no victory more compelling than the victory of a debater who fights and wins against a ‘straw man’.

An “Unreported” Precedent

Regardless of whether or not one likes it, the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Pak-Turk Schools case is a judgment of our apex court. As long as it is not set aside by the Supreme Court itself, it serves as a binding precedent. Article 189 of the Constitution states that to the extent that any Supreme Court judgment is based upon a principle of law, enunciates a principle of law or has decided a question of law, all other courts in the country are bound to follow it.

There are at least three principles of law on which the judgment appears to be based:

- The first principle is that the courts exercising writ jurisdiction have ample powers to direct de-registration of an NGO and handing over of its assets to another NGO, if provided with evidence that such a direction is necessary for national security. This principle is pegged on Section 42(5) of the Companies Act 2017.

- The second principle is that the federal government is bound to declare an organization a proscribed organization if it has reasons to believe that the organization has been involved in committing terrorism in a friendly foreign country. This is pegged upon Article 40 of the Constitution read with Section 11B of the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997.

- The third principle is that the Supreme Court can declare any organization a ‘proscribed organization’ if provided with sufficient evidence that the organization is a threat to our right to life. This is pegged on Article 184(3) read with Article 9.

This is precisely the kind of path-breaking, fertile and creative judgment for which law reports are on the lookout. Yet, the court has stated that this judgment is “not approved for reporting”. In the context of a judgment under Article 184(3) which relates to, by definition, matters of public importance, this direction is hard to appreciate. The court has exercised its jurisdiction for fundamental rights of the public but at the same time held that the public is not supposed to know much about it. As a result of this statement, the original text of the judgment is not freely accessible on the court’s website (although any citizen can obtain a certified copy by following an application procedure). It is also quite likely that because of such statement, this significant case will not be published by any of the commercial law reporters.

The Judgment in Context: Pakistan’s Turn to Authoritarianism

I have to be honest, when I first read this judgment, I found the court’s decision hard to square with the principles of constitutionalism and the promise of civil liberties which we have inherited from the founding fathers of our republic. But as I began writing this review of the judgment, I realized that I was unfairly singling out this institution – perhaps because of my singular love for it. Because I had grown up romancing the court as a liberty-loving institution, I had been ignoring the lesson that sociologists of law had been trying to teach us: judges, no matter how committed to their lofty ideals, cannot, for long, remain immune to the general trends of the polity that they function in.

The unfortunate reality is that our polity has, since long, been seeing a slide down the path of authoritarianism. Even though it may at first seem outlandish, the court’s opinion in the Pak-Turk Schools case is at least partly anchored in laws – draconian laws made by our Parliament in the wake of events like 9/11 and the APS attack. Two such laws relied upon by the court merit special mention: the Anti-Terrorism (Amendment) Act 2001 and the Companies Act 2017.

The Anti-Terrorism (Amendment) Act 2001 inserted, among other things, Section 11B into the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997. This law empowered the federal government to declare any organization a terrorist organization if it had “reasonable grounds” to believe in the organization’s guilt. In other words, instead of the general principle of criminal law (where guilt is attributed to individuals), guilt could now be attributed to entire organizations. Also, it did away with the need for framing charges, recording evidence, cross-examination and all those old-world principles of criminal law. This law also replaced the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard earlier used in criminal proceedings with the much lower “reasonable grounds” standard. The saving grace was that Section 11B allowed the “guilty” party to go and knock the door of courts to prove its innocence.

Likewise, Companies Act 2017 has only recently granted the SECP vast, dictatorial powers over all non-profits which have been registered by it. Three provisions of the 2017 Companies Act are specifically worth a mention. The insertion of subsection (5) into the famous Section 42 now allows the SECP to revoke the licence of any non-profit which in the Commission’s opinion “has acted against the interest, sovereignty and integrity of Pakistan, the security of the State and friendly relations with foreign States.” Section 43 allows the SECP to transfer all the assets of such a “convicted” company to “another company licensed under section 42, preferably having similar or identical objects to those of the company…” The new Section 172 allows the SECP to disqualify any company director if he or she has, in the Commission’s opinion, “acted against the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of Pakistan, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States…”

Any lawyer will be able to sense the dangers inherent in these penal provisions which are worded in extremely vague language. Before the Companies Act 2017, the SECP did not enjoy such draconian powers over non-profits. The most it could to a non-profit was revoke its non-profit status and convert it into an ordinary, profit-bearing company. Now, it can effectively destroy an NGO and hand over its property to someone else. Ironically, both the original Anti-Terrorism Act of 1997 and the Companies Act of 2017 were steered through Parliament by the government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif who himself had repeatedly become a victim of state authoritarianism.

To cut a long story short, the context behind the Pak-Turk Schools judgment is that during the unending ‘War on Terror’, our Parliament had already conferred draconian powers upon various state officials. What has happened now is that the courts have started exercising the same powers suo moto. Seen this way, the Pak-Turk Schools case just represents the next logical step in our polity’s steady slide down the path of authoritarianism.

The Future of Article 184(3)

Soon after the court’s decision in the case, the tenure of Chief Justice Saqib Nisar came to its end. There has since been a momentary lull in the juggernaut of suo moto actions. In his inaugural speech, the new Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Asif Saeed Khosa, made a point that “… this Court’s jurisdiction under Article 184(3) of the Constitution shall be exercised very sparingly …” He also promised that “an effort shall be made to determine and lay down the scope and parameters of exercise of the original jurisdiction of this Court under Article 184(3) of the Constitution ….” As a result of the Chief Justice’s promise, a much-needed debate about the future Article 184(3) has started, both amongst the judges as well as amongst lawyers.

I have written about the Pak-Turk Schools case in detail because it provides empirical data which can enrich this ongoing debate about Article 184(3). It is an eye-opener. It helps dispel the rosy depiction of Article 184(3) which has misled so many of us in the past. This depiction, cultivated perhaps unwittingly by judges, journalists, researchers and lawyers alike, used to present Article 184(3) as a magical remedy for getting a hold on corrupt politicians, indifferent bureaucrats, robber-baron businesspersons, tyrannical waderas and the likes – people who, presumably, could not be held accountable anywhere else because they enjoyed a stranglehold upon the entire state machinery. The great service which the tenure of Chief Justice Saqib Nisar has done for Pakistan, is that it has totally shattered this decades-old myth.

Since 2010, vocal skeptics of judicial activism have been warning us about the potential for arbitrariness, unfairness and opaqueness latent in the Supreme Court’s practice of Article 184(3). But it was in the tenure of the Chief Justice that we saw the full blossom of these evils with our own eyes. I think it was in 2018 that a critical mass of thinking Pakistani lawyers finally came to realize that equipping judges with arbitrary power is a recipe for tyranny – judiciary tyranny, which is the worst form of tyranny amongst all its forms. In 2018, we realized that the sword of judicial tyranny didn’t just hang over the heads of the so-called “corrupt” elements of the society, it hung over the heads of all of us – teachers, doctors, businesspersons, researchers, lawyers, lower court judges, everybody.

Proposals for Reform

Based on my review of this case, I would like to propose a few concrete steps which can be taken to restructure of the Supreme Court’s power under Article 184(3) and make it less prone to abuse.

1. The first proposal is that the Supreme Court should address a glaring ambiguity in the text of Article 184(3). What does the term “question” mean when used in the phrase “question of public importance with reference to the enforcement of fundamental right”? To my knowledge, this issue has not been seriously addressed in any judgment so far.

In the common law tradition, we have three types of questions: “questions of law”, “questions of fact” and “mixed questions of law and fact”. My review of the Supreme Court’s cases under Article 184(3) shows that, at the moment, the court is deciding all kinds of questions under this jurisdiction. This becomes the root cause of many errors. It is a matter of common sense that the Supreme Court of a country, its court of last instance, is not the most suitable forum for determining questions of fact. Such questions are best determined through the trial process, followed by an appeal. Therefore, in my humble view, the term “question” in Article 184(3) should be interpreted as referring to questions of law only.

I also draw support for this common sense interpretation from the way the term “question” has been used throughout the chapter of the Constitution dealing with Supreme Court. Besides Article 184(3), there are two other articles in this chapter which expressly confer a jurisdiction upon the court to decide specific kinds of “questions”. Article 185(2)(f) obliges the Supreme Court to hear appeals from cases where a High Court certifies that a “substantial question of law as to the interpretation of the Constitution” is involved, Article 186 obliges the court to tender an opinion to the President on “any question of law which he [i.e. the President] considers of public importance”. Article 189 drives the point home when it says that whatever decision the Supreme Court makes on “a question of law” is binding precedent for courts below it.

To sum up, the manner in which the term “question” has been used throughout the Constitution’s chapter on the Supreme Court strongly suggests that the framers envisaged it as a court the primary function of which was to decide “questions of law”. Such questions may be referred to the Supreme Court by the President (Article 186) or by the High Courts (Article 185(2)(f)), or selected by the court itself (Article 184(3)). There is nothing in the Constitution to support the view that the Supreme Court was meant to be adjudicating “questions of fact” in its original jurisdiction. Article 184(3) should be interpreted in this textual context.

2. The second proposal is that the court should revisit its jurisprudence on the necessity of meeting threshold requirements before initiating proceedings under Article 184(3). The Supreme Court’s view presently is that these requirements which are applicable to other constitutional courts – “locus standi”, “bona fide” and “absence of alternative remedy” – do not apply to the Supreme Court. This view, which dates back to the late 1980s, can be revisited.

Very few people know that the Supreme Court has not always held the view where threshold requirements become redundant in the exercise of its original jurisdiction. Equivalents of Article 184(3) have existed in our Constitution since long. Even the Constitution of 1956 gave the Supreme Court power to exercise original jurisdiction to “issue … directions, orders or writs, including writs in the nature of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari, whichever may be appropriate, for the enforcement of any of the [fundmental] rights…” But, before the late 1980s, the court never exercised this power, perhaps out of deference to the general principle that cases should start in courts below and only later come up to the Supreme Court in appeals. The first case in which the court decided to side-step the jurisdiction of the High Courts was Benazir Bhutto v Federation (PLD 1988 SC 416), where it entertained a petition which could have also gone to the High Court. A year later, in Darshan Masih’s case (PLD 1990 SC 513), the court took its first suo moto action. In these judgments, the court surprisingly pointed out that threshold requirements found no mention in the text of Article 184(3), even though they had been mentioned in the text of Article 199, the provision governing the jurisdiction of the High Court. The court interpreted this omission as implying a legislative intent to free the Supreme Court, the loftiest of all courts, from all encumbrances which otherwise bound courts of law.

There is also actually nothing in parliamentary debates around Article 184(3) of the 1973 Constitution or, for that matter, Article 22 of the 1956 Constitution which can confirm this rather self-serving interpretation. Even if we accept that this laissez faire interpretation was suitable for a time when our polity was recently emancipated from martial law and the Supreme Court was struggling to find a place for itself in the constitutional scheme, in today’s context, it may not the best approach. The Pak-Turk Schools case, and a lot of cases from the year 2018, provide ample evidence for this argument.

Even the most emphatic admirers of Article 184(3) concede that it is a discretionary jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and must be equitably used. This is because the relevant phrase used in the Constitution goes like this: “Court shall… have the power to make an order… ” instead of “Court shall… make an order…” This means that even though the Constitution does not stipulate these threshold requirements, there is nothing which prevents the court itself from adopting such threshold requirements for the exercise of its power. In other words, the court can clarify that while it “has” a lot of power under Article 184(3), in future it will not “exercise” it until formally petitioned by a bona fide petitioner, who has locus standi, and has exhausted all alternative remedies.

3. The third proposal is that the Supreme Court should revisit its present approach to constitutional interpretation, especially its approach to the interpretation of fundamental rights adopted in the famous case, Shehla Zia v. WAPDA (PLD 1994 SC 693). It was in this case that the court definitively repudiated a traditional canon of interpretation whereby words used in the Constitution should have been given a plain, textual meaning. In case of Article 9 of the Constitution which promises that “No person may be deprived of the right to life… save in accordance with law”, the plain meaning would probably be: “No accused person may be executed by the state without being afforded a trial”. Instead, in the Shehla Zia case, the court held that such a term should be interpreted as the right to enjoy “all such amenities and facilities which a person born in a free country is entitled to enjoy with dignity, legally and constitutionally” and a lot more. In other words, the court held that the Constitution promised to all persons “the good life”, as the courts saw it, from time to time.

Without expressly saying it, our Supreme Court adopted a theory of interpretation known to its supporters all over the world as the “living Constitution” approach. According to this approach, constitutional terms like “life” do not have any fixed meaning; the meaning of these terms keeps changing from time to time and has to be determined by the judges. Critics of this approach caution that such an approach, while sounding noble, actually empowers judges with the ability to do whatever they will, in the name of our Constitution. I think most people will agree that what the Supreme Court has done in the Pak-Turk Schools case in the name of our right to “life” is a bit of a stretch and lends credence to critics of the “living Constitution” approach. In the twenty-four years between the Shehla Zia case and the Pak-Turk Schools case, there have actually been hundreds of cases where judges have given a very loose interpretation of fundamental rights.

Let me also mention a recent well-known case which perhaps provides the best illustration for this point: Barrister Zafarullah v. Federation (Const. P. 57/2016), popularly known as the Dam Fund Case. In this case, a four-member bench of the honourable Supreme Court effectively held the “right to life” mentioned in the Constitution to mean the right to life with a certain level of minimum per capita dam-water storage. Since we did not have that level of per capita dam-water storage, the Supreme Court decided to intervene and set up a ‘dam fund’.[6] The Dam Fund case is, in a way, a blessing in disguise. By taking the ‘living Constitution’ approach to its logical extreme, it has exposed the absurdity of it all. In the wake of this eye-opening judgment, the most sober jurists in Pakistan have started calling to revisit the lax approach to constitutional interpretation which has taken root in our legal culture since the Shehla Zia case.

In an article titled Abuse of Justice, senior Supreme Court Advocate, Dr. Tariq Hassan, has critiqued the court’s ruling in the Dam Fund case.[7] Dr. Hassan contends that “[a] plain textual interpretation of Article 9 suggests that it deals with the divestment of a right rather than the provision of a right. There is no direct obligation to provide water in this Article…” Without making it very obvious, Dr. Hassan has challenged the hallowed Shehla Zia case doctrine under which the fundamental right to life means a life with “all such amenities and facilities which a person born in a free country is entitled to enjoy …”

Please note that critics of the “living Constitution” approach are not arguing against judicial activism for protecting the few fundamental rights which the framers of our Constitution actually intended the Supreme Court to protect – like the right of citizens not to be killed in a police encounter and the right not to be subjected to state-enforced disappearance (ironically these are the rights which our activist Supreme Court seems to be the least interested in vigilantly protecting). I am only arguing that the Supreme Court can do us a greater service by protecting fundamental rights which are explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, instead of wasting its creative energies on expanding the meaning of fundamental rights through “dynamic interpretation”. Courts should do their own job and leave some of the good work for others as well, such as parliamentarians, civil servants, journalists, academics and, of course, poets.

4. The fourth proposal is that the court should constitute a special bench for hearing petitions under Article 184(3), comprising of as many of its senior-most judges as can be practically spared. This calls for a departure from the present practice of fixing all the sensitive Article 184(3) petitions before Bench I, which generally includes two relatively junior judges other than the Chief Justice who heads the bench. As a result of the present practice, in 2018 we saw the entire judicial power of the state concentrated in the hands of one person – the Chief Justice of Pakistan. And even though that one person may have been honest, learned and patriotic, as predicted by constitutional theorists, the result of such concentration of powers had been disastrous. If the Supreme Court is ever to become the deliberative, collegiate institution which the framers of our Constitution intended it to be, such a practice would have to change. All decisions regarding Article 184(3) petitions, including the critical decision of issuing notices, should be taken by a bench comprising the senior-most judges instead of being taken by the Chief Justice’s bench.

Some lawyers and judges would go even further and suggest that Article 184(3) petitions should be heard by a full 17-member bench of the Supreme Court. This extreme position is not entirely unfounded if you consider the following three points.

- Firstly, there is that brief but historic dissenting note[8] by the honourable Justice Qazi Faez pointing out that the Constitution does not give the Chief Justice of Pakistan any personal power to entertain petitions under Article 184(3) or to issue suo moto notices; the Constitution confers this power upon the Supreme Court.

- Secondly, as pointed out in a petition filed in 2015 by eminent Supreme Court lawyer, Mian Shafaqat Jan, our Constitution’s chapter on Supreme Court, unlike its Indian equivalent, does not explicitly empower the court to create benches.[9] This means that if the court (i.e. the 17 judges) has any power to constitute benches, this power is an “implied” power and must be used reasonably and sparingly. Petitions under Article 184(3), being totally discretionary in nature, are perhaps the least eligible to be delegated to a bench, rather than being heard by the full court.

- Thirdly, in Mustafa Impex v. Federation (PLD 2016 SC 808), the Supreme Court restrained the Prime Minister from usurping the institutional powers of the federal Cabinet and also barred delegation of the Cabinet’s powers to cabinet committees. There is at least a moral argument that the court should also exercise similar restraint in delegating its institutional powers to the Chief Justice or to the benches constituted by the Chief Justice. Critics argue that if the 60-member federal Cabinet is bound to decide all cases sitting together as a collegiate body, why isn’t the 17-member court bound to do the same?

5. The fifth and final proposal is that from here onwards, case records of every single case under Article 184(3) should be made public. The petition, replies, written arguments, order sheets and judgment should all be uploaded on the Supreme Court’s website. If these are cases of “public importance”, why not let the public review their proceedings?

This may look like the smallest among the reform proposals but it may turn out to be the most effective. In judicial corridors, reputation matters. If judges know they are functioning in a system where any irregularities can easily be called out, they will avoid them. A judge from another country once said, “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.”

Let me conclude with a recap of my proposals:

- The term “question” in Article 184(3) should only mean a “question of law”;

- Even though permitted, the court should not exercise powers under Article 184(3) until it is formally petitioned to do so by a bona fide petitioner, who has locus standi, and has exhausted all alternative remedies;

- The court should focus on actually ‘defending’ fundamental rights mentioned in the text of the Constitution, instead on ‘expanding’ on their scope through interpretation;

- Petitions under Article 184(3) should be handled, from the beginning till the end, by a bench comprising a large number of the senior-most judges;

- Last but not the least, the case record of all petitions under Article 184(3) should be made public.

———-

References

[1] https://tribune.com.pk/story/1876161/2-sc-directs-govt-declare-gulen-group-banned-outfit/

[2] https://tribune.com.pk/story/1559691/1-shc-extends-stay-turkish-teachers/

[3] https://www.dawn.com/news/1403838

[4] https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/170606-A-divisional-bench-of-Islamabad-High-Court

[5] I was not present in court at the time this case was called but my account of what happened is based upon the report of at least two eye witnesses.

[6] http://www.supremecourt.gov.pk/web/user_files/File/Const.P._57_2016.pdf

[7] https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2018/12/tariq-hassan-abuse-judicial-process/

[8] https://tribune.com.pk/story/1708423/1-justice-qazi-isa-questions-cjps-decision-reconstitution-bench/

[9] https://www.dawn.com/news/1223719

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which he might be associated.

Dear av.Umer Gilani

I am Halit Esendir . I am founder PTICEF in Pakistan.

I was living nearly 7 years (1997 – 2003) in Islamabad. Also I am founder AFGAN TURK NGO in Afganistan.

InsaAllah we are successful

We are motto 2 country one nation Pakturk School’s

Zindabat Pakistan Zindabat Turkey

Cive cive Pakistan

Huda Hafiz

Your sincerely

Halit Esendir.

Dear Omer Gilani;

I would like to thank you for this article. I hope it will enlighten many of our Pakistani brothers about the case. They unfortunately are not aware what is going on really.

Besides I am upset of the decision given by Supreme Court. I was there in Pakistan for almost 13 years. PakTurk served to nation a lot. They did not deserve this. We know these are political issues. Our sincere love between two brotherly nations will not fade out.

I hope Court will reverse from its decision.

I hope the issue between Pakistan and India will resolve without any loss and damage and it is my prayer for my Muslim brothers and sisters. No war brings happiness and prosperity..

Huda hafeez. Fi emanaallah.

Pakistan Zindabad. PakTurk dosti paindabad.