Jinnah’s ‘Presidential’ Pakistan

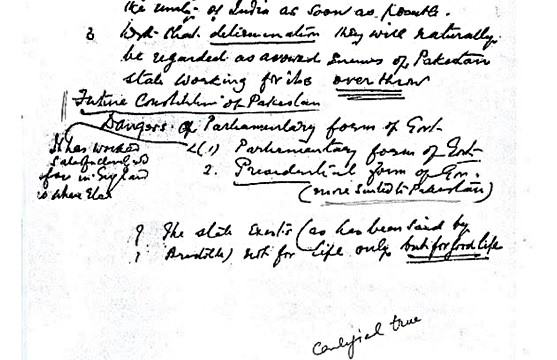

A little while back, while representing Sindh at the Youth Parliament Pakistan (YPP) in Islamabad, I had the good fortune of coming across a rare hand-written note by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, dated July 10, 1947. It is perhaps the only surviving personal record of the founder’s constitutional plans, which was written days before the birth of a nation, which in its infancy, resembled an arbitrary patchwork made of the carved west Punjab and east Bengal, a hostile Congress-governed Frontier Province, a nationalist Sindh that was still nursing its wounded pride after its own ‘One Hundred Years Of Solitude’ at the hands of the Raj, and a Balochistan that did not even have a central government, with the majority of its population living in the princely states. It is in this context that Jinnah, a statesman par excellence, wrote the following lines: “Dangers of Parliamentary Form of Government: 1) Parliamentary form of government – it has worked satisfactorily so far in England nowhere else; 2) Presidential form of government (more suited to Pakistan)”.

The eminent jurists on the YPP panel referred to the constitutional role Jinnah helmed after partition – Governor General and not that of the Prime Minister – to confirm his intentions of ushering in a presidential system, similar to that of the US, with a directly elected senate having equal representation from all federating units.

Jinnah’s aversion to the parliamentary form of government is ominous, which in his own words had “worked satisfactorily so far in England nowhere else.” Unlike the unitary UK, which is centrally governed by the Westminster, Pakistan was a federation that came together on personal guarantees provided by Jinnah to the people of Balochistan, Bengal, Sindh and Frontier province. As a constitutional lawyer he had sought to formalize the contract between the young state and its people by drawing up an equitable constitution that would once and for all put an end to the lifelong disparity between the centre and the smaller federating units. One cannot deny the genius behind Jinnah’s reservations since this disparity contributed to the fall of Dhaka and the deprivation in Balochistan. In the recent years, this great imbalance of power has created a lack of consensus on CPEC, a limited success of the National Action Plan in KPK (APS, Bacha Khan University), Sindh’s water case vis-à-vis Kalabagh Dam and Greater Thal canal as well as the discontent found in the Seraiki belt.

Alas! Betrayal and a failing health prevented Jinnah from realizing his constitution making plans in the intermediate 14 months between the time of this note (10-07-47) and his demise (11-09-48).

Jinnah’s Failing Health

The truth about Jinnah’s affliction (tuberculosis) was the best-kept state secret of the time. Akbar Ahmed in his book Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin (page 10) writes, “By the time Mountbatten came to India as Viceroy in 1947 neither the British nor the Congress suspected the gravity of Jinnah’s illness. Many years later Mountbatten confessed that had he known he would have delayed matters until Jinnah was dead; there would have been no Pakistan.”

Ultimately the life threatening tuberculosis, worsened by his heavy smoking – fifty cigarettes a day of his favorite brand, Craven A – and a punishing work schedule proved fatal. Moreover, Mountbatten’s words also proved to be portent of the power vacuum Jinnah’s illness helped create. One such episode is recorded by AIML Punjab’s chief organiser Sardar Shaukat Hayat Khan in his book The Nation That Lost Its Soul (page 75) that, “in 1945 when Liaqat Ali Khan (then AIML Secretary) came to know of Jinnah’s fast deteriorating health he entered into a secret pact with the Congress vis-à-vis senior congress leader Bhalubai Desai.” This was a political insurance that Liaqat Ali Khan sought vis-à-vis a power sharing agreement in an ultimately united India in return for gradually phasing out the struggle for a separate Muslim state after Jinnah’s demise.

Although this event has been largely played down by the state’s official narrative, however, Jinnah’s private secretary K.H. Khursheed in his book Memories Of Jinnah (page 38) confirms this gross miscalculation by the Nawabzada that attracted the displeasure of Jinnah who, “immediately wanted to relieve Liaqat Ali Khan of his party position.” Nonetheless, Jinnah was brought around by senior party members in delaying the sacking in order to avoid creating a division in the party ranks at a time when maintaining a united front in face of the British and the Congress was crucial.

Nevertheless, even after partition, the political opportunism failed to wither away and when Jinnah left for Ziarat, Balochistan to recuperate, the petty ambitions of the acolytes returned with an even greater zeal. This resulted in the botched operation, led by the tribal warriors, to take Kashmir by force. This ill advised move orchestrated by the Prime Minister – then the acting Chief Executive in absence of Jinnah – weakened Pakistan’s constitutional and moral claim over Kashmir and provided the excuse for Indian forces to occupy Kashmir in perpetuity.

Chaudhry Mohammad Ali (the fourth prime minister of Pakistan) in an interview given to K.H. Khursheed, which is recorded in his book Memories Of Jinnah (page 82), minces no words in taking names behind this operation, “on the sole initiative of Liaqat Ali Khan Kashmir war was started from Pakistan’s side. Jinnah had no say in this regard.”

This contention is also supported by Jinnah’s personal physician Lieutenant Colonel Dr Ilahi Bakhsh’s in his book, With The Quaid-I-Azam During His Last Days, (a book that remained banned from 1949 till 1976 for ideological reasons) “Jinnah became shocked at this arbitrary action [Kashmir war] taken by Liaqat Ali Khan and immediately denounced it.” This reprimand led to the permanent souring of relations between the Governor General and the Prime Minister.

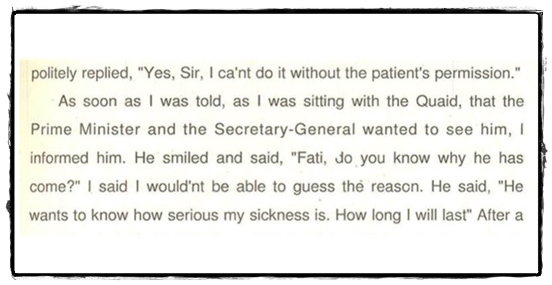

Fatima Jinnah in her heavily censored biography on Jinnah, My Brother (Quaid-e-Azam Academy), written in 1955 but kept from being published until 1987 for the same ideological reasons, speaks of an episode that seems to confirm the acrimony between the two leaders in the difficult final days of Jinnah’s life. Ms. Jinnah recounts a visit by Liaqat Ali Khan at their Ziarat residency when, just before the PM’s brief audience with him, Jinnah said to his sister “Fati, do you know why he has come?… he [Liaqat Ali Khan] wants to know how serious my sickness is. How long I will last?”

I was not at all surprised to find out that the pages containing the said lines were removed even from the much-delayed 1987 version. Writer Akhtar Balouch in his research piece, The deleted bits from Fatima Jinnah’s ‘My Brother’, (September 16, 2015, Dawn.com), writes, “The perpetrator of this feat was Mr Sharif-ul-Mujahid of the Quaid-i-Azam Academy. I went to Mr. Sharif and asked him the reasons. ‘Those pages were against the ideology of Pakistan and I had to take care of it,’ he said.”

In the end Pakistan was not meant to be the constitutional state Jinnah envisioned it to be due to a combination of illness and bad company, whereas, in the neighboring India, with Nehru at the helm for many years, the Dalit leader Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was asked to pen the Indian Constitution (passed on 26 November, 1949). It is only befitting that the last conversation of Jinnah’s life was about a burning desire to complete this sacred charter.

Postscript

Jinnah’s biography My Brother is a blend of timelessness and timelines that looks at the inner world of a genius, in the most beautifully imperfect and human way possible. It is a psychological profile of the Jinnah family that traces the humble origins of a merchant family from Gondal, Gurjat that dared to look in the eyes of the mighty British Empire and triumphed. Written by Fatima Jinnah, Jinnah’s confidante, friend, and chief ally, the narrative is at once edifying and poignant. The author’s portrayal of her family’s inclination to Sufi ethos, their personal attachment to Sindh vis-à-vis Karachi and the difficult last days of Jinnah’s life surrounded by treacherous confidantes and a failing health helps reader fathom the genesis of the existential questions that have hitherto remained unanswered.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which he might be associated.

1 comment