Pakistan’s Recent Counter-Terrorism Measures: A Critical Look

When the harrowing attack of 16 December, 2014 took place, it felt as if the world had stopped spinning – for 144 families, it did.

Feeling a surging sense of duty, spiked with a sinking sense of despondency, we tried to caress our demons to rest by promising ourselves we would never forget.

But.

Amidst blackened display pictures and sombre hushed tones that were self-patted assurances that we had done all that we could, we forgot.

But what about the state? Did the state forget?

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif (rightfully and in his usual reductionist fashion) dubbed the occurrence as a “national tragedy.”

What happened next?

Eight days later, after an All-Parties Conference (APC), the PM introduced the National Action Plan (NAP). Soon after, in pursuance of the NAP, military courts were put into place with a life expectancy of two years. They brought with them the promise of criminal justice reform in Pakistan – one for which these two years, it was hoped, would be sufficient. Let’s take a look at these one at a time.

The National Action Plan (NAP)

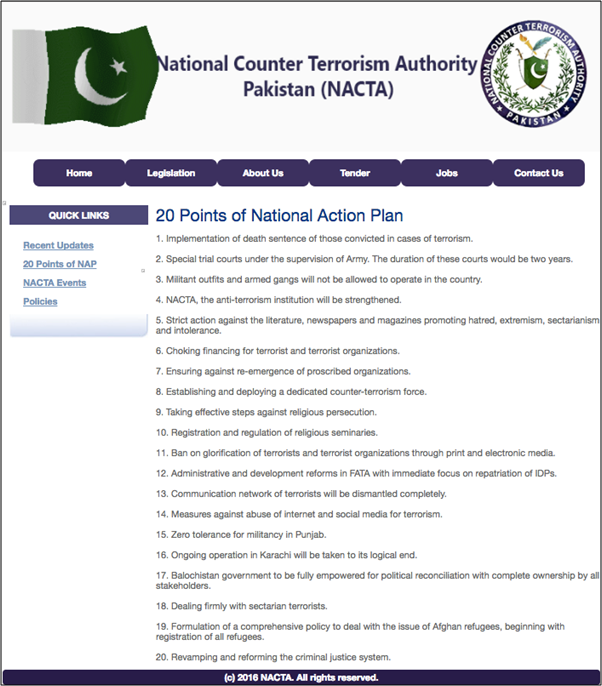

The NAP has been referred to as many things, but most ironically it has been called a “comprehensive plan of action against terrorism.” [An overview of the NAP and associated timelines may be found here.]

Though, the policy-drafting abilities of Pakistan’s government ought to be called into question, when one realizes this – these 20 points are the extent of the NAP:

Fig. Screenshot of the NAP from the National Counter-Terrorism Authority (NACTA) webpage.

Since the creation of the NAP, almost every decision made by the government has been publicized as being under the purview of, or pursuant to the NAP. Except, the NAP is as general a documentary set of guidelines as a four-year old child’s list for their birthday.

Moeed Yusuf captures this sentiment perfectly, by stating simply, “We have a marker that everyone seems to consider fair in terms of judging the government’s performance, and the government seems to recognise this. The problem is that there isn’t much to measure against. NAP isn’t a ‘plan’…. The government needs to give it real meaning by devising specific action plans for each of its achievable elements and performing sincerely against those. Else, it will be blamed for failure; and we’ll keep firefighting through kinetic means.”

Recently, this has also been noted on the political front, with Mr. Bilawal Bhutto heavily criticizing the NAP in all its glory, including pointing out that the Parliamentary Committee on National Security, as discussed in the APC in 2014, has still not been formed.

The Military Courts

Soon after, through the 21st Constitutional Amendment and the Army (Amendment) Act 2015, military courts were established. Lacking transparency and attacked for being both draconian and in violation of fundamental human rights, the military courts did one thing that no one had succeeded in doing until that point — they gave ordinary citizens some semblance of hope.

Whether that sense of hope was a placebo effect or whether the formation of military courts, and their speedy trials thereafter, did in fact provide some form of relief to the citizens of Pakistan – one cannot be sure. The Pakistan Army had been able to provide this sense of security earlier as well through the military actions – carried out as actions in aid of the civil power as under Article 245 of the Constitution of Pakistan – such as Zarb-e-Azb, carried out to target militants in the northern areas of the country.

But was this really the answer?

Military courts were created as a measure-of-last-resort, at a time when they seemed to be the only intuitive and expedient solution. They were validated by the Supreme Court in its judgment, wherein the former Chief Justice of Lahore High Court, Justice Umar Ata Bandial ruled that:

“The terrorist militants operating in the country … do not have a unified command, nor do they wear an identifiable uniform or distinctive sign in order to be recognized; they operate by resort to subterfuge, perfidy and disguise without regard to the rules governing war. The said elements and characteristics make the case of terrorist militancy more sinister than enemy state combatants who abide by the aforementioned international norms. The treatment of belligerent citizen[s] and unlawful combatants in custody who have waged war against the state is not just a matter of municipal law. The subject also attracts the principles of public international law on armed conflict and war.”

The Supreme Court, it may be understood, therefore stated that Pakistan is in a de facto state of war. Any international lawyer knows that in the state of war, the role of international humanitarian law (IHL) kicks in. This seemed in line with the political opinion at the time, especially from the government itself, since PM Nawaz Sharif, in the wake of the APS attack, said, “Such attacks are expected in the wake of a war and the country should not lose its strength …”

Except, there was no formal notification to this effect. There was no official acceptance or notification that Pakistan was (and still is?) in a state of war.

As of earlier this year, the tenure of the military courts has come to its end, with a number of political party representatives saying they see no reason or justification for the same to be extended.

The real question, though, remains: have the military courts done their part before they were put to sleep?

A total of 275 cases have been referred to the military courts and 12 convicts executed, the Interior Ministry says. The tribunals have sentenced 161 people to death and handed jail terms, mostly life sentences, to 116.

It must also be pointed out that to achieve this expediency in terms of convictions, the moratorium on capital punishment was lifted – another act that attracted a lot of criticism from human rights’ groups globally.

The military courts, as discussed before, were created as a stopgap function. To this end, it would appear that they may be credited as having fulfilled their purpose.

But the long-term, permanent solution seems to have drifted to the back of the state’s pre-occupied (?) mind, and placed on the top-most shelf at the very end, being kept company by other issues such as education and healthcare.

As a notable lawyer weighed in: “The military courts achieved their objective partly in terms of giving sentences to people, but their real purpose was to act as an incentive to upgrade the existing Anti-Terrorism Act. It was an inbuilt legislative inducement. But that did not happen. The long-term objective was not achieved.”

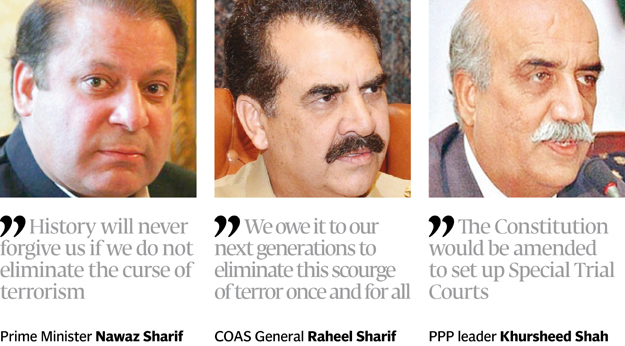

It is therefore a little ironic for the Prime Minister and other top officials to have passed statements like these, and then not followed up on them, evidenced by the lack of institution of any longstanding mechanism that may help or aid in the total prevention or elimination of terrorism.

Fig. Comments from various notable authority figures in light of the APS attack.

The Legislative Conundrum

Notwithstanding the ability or capability of our legislators in Parliament (or the Majlis-e-Shoora as it is known), perhaps the biggest issue faced by them is to draft a law that is widely accepted by the masses as being ‘suitable’. For instance, when the Protection of Pakistan Act (PoPA) was passed, it was immediately slammed as being too draconian in nature, and the fear that it would be misused and exploited became the prevalent opinion.

How then do legislators decide what to do? Do they appease the masses and enforce lenient laws? Or do they understand the nature of the problem at hand and ignore the adjectives used to describe their legislative endeavours?

Maybe the problem is not with the legislative body. Perhaps it comes down to the execution stage, for if there was adequate faith in the latter, there would be little reason to fear the exploitation of the acts of the former.

Furthermore, it seems that all recent legislation, especially with regard to Pakistan’s counter-terrorism efforts, is reactionary in nature: the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) came about originally in 1997, and the PoPA was passed in 2014 around the same time that Zarb-e-Azb was taking off. However, both the formation of the NAP and the military courts only came about as a direct consequence of the ghastly APS Peshawar attack.

Could stricter measures, and better legislation with greater foresight, have helped prevent this abhorrent display of terrorism? Could a stitch in time have saved nine?

Perhaps, we shall now never know.

The Criminal Justice System in Pakistan – Need for Reform?

Before leaving office, the 44th President of the United States (POTUS), Barack Obama, went back to his roots – where he was once the first African-American editor of the Harvard Law Review, he now became the first POTUS to contribute an article to the same.

Obama’s article was centred around criminal justice reforms that had taken place during his tenure in the Oval Office through the executive action of the President.

One may argue that the same breadth and depth of powers are not available to the President of Pakistan, and so this comparison is made redundant. Except, the Constitution of Pakistan, under Article 89, grants the President the right to promulgate ordinances, which may subsequently be enacted as a formal Act of Parliament pending approval by the same.

Notwithstanding the role of the President, much needs to be done to strengthen the state’s (civilian) institutions, including (and especially) the courts and the process of criminal trials, including but not limited to, trying to eradicate the massive backlog that exists. It may be argued that, “Parliament’s acquiescence in setting up military courts has further compromised public confidence in the legal system and perhaps delayed urgently needed reforms within.”

But perhaps the scariest realization is that, “… our recent history has also illustrated that dysfunctional or absent justice systems provide a convenient pretext for extremist elements, promising utopian visions of an equitable society, to expand their influence among angry, discontented populations.”

Parallel Criminal Justice Systems and Inconclusive Litigation

At one point in time, not too far back in history, there were four parallel criminal court structures operating in Pakistan:

- The criminal courts functioning under the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) and the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC);

- The Anti-Terrorism Courts (ATCs), formed under the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997 (ATA);

- The criminal courts under the PoPA (which were never really made functional); and

- The military courts, as under the 21st Constitutional Amendment and the 2015 amendment to The Army Act.

The idiom, too many cooks spoil the broth, comes to mind.

Despite these parallel structures operating concurrently, the backlog still exists and there is only more confusion over which court a case ought to be taken to. The definition of terrorism and the subsequent scope of military courts and the ATCs is different between themselves. But adequate training on how to interpret these laws and where/how they should be applied is still a crucial missing factor in today’s system: after all, for most legal criminal proceedings, the starting point is the police [and the registration of a first information report (FIR)].

It may be unfair to place the entire burden of blame upon law enforcement agencies (LEAs) – the responsibility also lies with the drafters of the laws. Take the ATA for instance. Section 6 of the ATA attempts to define terrorism, whereas Section 7 of the same lays out the punishments for the acts under the preceding section.

Now a two-page definition of terrorism is all well and good if it serves an exhaustive function that helps to narrow down the scope of the Act. Unfortunately, Section 6 of the ATA does quite the opposite. As is adeptly described by Zaidi, when he notes that,

“Litigation which is tangential to hardcore terrorism accounts for a huge proportion of cases tried in the… ATCs in Pakistan, and thus takes up a correspondingly large proportion of [its] time and resources… This detracts them from devoting time and energy to the real hardcore terrorist cases, many of which get neglected due to the backlog of cases in ATCs. It is an established fact that police will incriminate [those] accused under [the ATA] that they want to get long prison sentences for, or deny bail, and many litigants will misuse the stricter sentences given in ATCs to bring false cases against their rivals…. Then, there is the problem that the ATA casts a very wide net. Since section 6 of ATA gives a very broad definition of terrorism, many criminal actions fall under the ambit of terrorism. Brutal murders are terrorism, so is aerial firing which creates terror in the public, as well as damaging an electrical transformer; all are considered as creating terror in public, and fall under the purview of ATA. This wide ranging definition creates a host of offences which can be tried by ATA, and the sole criterion needed is that it should ‘create terror in the public’. To add to this problem, the interpretation of what terror in the public entails is being done by unqualified, poorly trained police officers of lower rank, who are also susceptible to external pressures and corruption. Thus, section 6… becomes a tool in the hand of incompetent, unequipped police officers to register cases under the ATA, which [only] adds to the huge caseload seen in poorly equipped ATCs.

But there is more to ATA than just the provisions contained therein…

The Fourth Schedule and Proscribed Entities

Proscribed organizations as under Section 11B of the ATA form the First Schedule of the ATA. The second amendment to ATA brought within its scope the proscription of individuals as well, to be listed under the newly added Fourth Schedule – individuals that were linked to the aforelisted proscribed organizations. This amendment also noted the restrictions that were to be exercised with regards these proscribed (simply put: banned) actors.

The list of proscribed organizations as it currently stands (as of 31 January 2017) is as follows:

Fig. List of Proscribed Organizations as per NACTA’s publicly available record, including those enlisted under UN S/RES/1267 (1999).

Despite initial disagreements over the publicizing of this list, NACTA and the Ministry of Interior finally decided to make the list public in 2015, with claims that the list was ‘under review’. Except, no organizations were added to this list in the period between 2013 and 2015. And those that were already part of the list were not properly communicated to the LEAs.

Tahir Alam Khan, IG Police Islamabad was also among the officers who were not ready to accept the list of banned organisations issued by the government. When he was confronted by The News regarding continuous permissions and support of the Islamabad Police for repeated programmes, protests and public meetings of banned pro-Taliban organisation Ahl-e-Sunnat-Wal-Jamaat (ASWJ), formerly Sipah-e-Sahaba-Pakistan (SSP), Tahir Alam maintained that the ASWJ was not a banned organisation. When his attention was drawn to the list of proscribed organisations, he said no such list was ever communicated to him.

Now, on the other hand, if we take a look at the proscribed actors under the Fourth Schedule, we can see that these individuals under the Fourth Schedule are not allowed “… to visit institutions of learning, training or residence where persons under 21 years of age are found. Similarly, public places such as restaurants, television and radio stations or airports are out of bounds for them. They are also forbidden from taking part in public meetings or processions, or from being present at an enclosed location in connection with any public event.”

Let’s perform a simple 2+2, shall we?

Looking at item number 32 on the NACTA list of proscribed organizations, we see that ASWJ is, indeed, a proscribed organization. That would lead one to presume, both intuitively and logically, that the leader of said ASWJ would be part of the Fourth Schedule (he is) and, therefore, would be subjected to the restrictions as under the ATA.

However, unfortunately, this is not the case.

Fig. Headlines from DAWN, 29 November 2016 (the article discusses the Lahore High Court’s approval to ASWJ chief, Ahmed Ludhianvi, to contest the Jhang by-election)

Former Federal Secretary, Interior, notes in a recent article how the Fourth Schedule only made things simpler for the LEAs, but its implementation has allowed it to become redundant:

“The solution devised through the Fourth Schedule was so manageable that rather than looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack, one would have ample time to identify potential criminals (with input from all intelligence agencies and anyone else one would want to consult) and then have unbridled powers to monitor them…. To watch, prevent and expose these 8,000 or so dangerous ideologues, financiers, hit-men, etc we have around 1,500 police stations across the country — which means that, on average, each SHO has to watch only five people or a DPO about 80, give or take a few. Now, is that not a manageable task? … The only explanation for the apathetic use of the Fourth Schedule seems to be that our rulers are tasking the police with matters that detract from tackling terrorism. This is confirmed by the government’s cavalier attitude in allowing persons on the terrorist list to compete in parliamentary elections. Like NAP, the casual neglect of the Fourth Schedule reflects the government’s misplaced priorities.”

The Current Scenario and ‘Misplaced Priorities’

The past week can be summed up in the following sentence of four disjoint, but connected phrases:

Four cities; four provinces; five days; eight attacks.

Put together, these provide an overview of the most recent wave of terrorist incidents in Pakistan over the past week:

More than 100 people have lost their lives in recent wave of terror attack in Pakistan beginning from Lahore where senior police officials were targeted… The security forces that include police and armed forces, judges, media personnel and ordinary people including women and children are targeted in the eight terrorist attacks in five days… All the four provinces and FATA tribal agencies came under these attacks.

At such a time, what, you may wonder, is the top civilian and military brass thinking about?

The Pakistan Super League (PSL) Final of course.

The issue was discussed at length during a top-level security huddle convened by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and attended by the Army Chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan, Finance Minister Ishaq Dar, Chief of General Staff, Lieutenant General Bilal Akbar, Intelligence Bureau Director General Aftab Sultan, National Security Adviser Lieutenant General (retired) Nasser Janjua and others, informed official sources told The Express Tribune.

Although an official statement did not say if any decision was taken on hosting the PSL final in Lahore, sources said the premier gave the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) his go-ahead to do so after exchanging views with his aides and the security command. The source said, “The premier told participants that he wanted to see the Pakistan Super League (PSL) final in Lahore even if the entire city had to be brought to standstill.”

But – you ask – surely the government must have been working hard on the right track in recent times, generally. There must be concrete steps the government must have taken, if not just for countering terrorism, then, perhaps, for alleviating poverty, or improving the healthcare system in Pakistan, or increasing the literacy rate of the country with better education, etc.

Earlier, in January, The Economist reported as follows:

“It is an article of faith for Mr Sharif and his party, the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N), that investment in infrastructure is a foolproof way of boosting the economy. His government is racing to finish umpteen projects before the next election, due by mid-2018, including a metro line in Lahore and a new airport for Islamabad… Pakistan’s infrastructure is underused because the economic boom it was meant to trigger has never arrived… terrorism and insurgency have put off investors, both foreign and domestic. The country is also held back by inefficient and often cartelised industries, which have fallen behind rivals in India and Bangladesh. Exports… have been shrinking for years. Much more needs to be done to create an educated workforce. Almost half of all those aged five to 16 are out of school—25m children. Health, like education, is woefully underfunded, in part because successive governments shy away from taxing the wealthy. Only 0.6% of the population pays income tax. As the World Bank puts it, Pakistan’s long-term development depends on ‘better nutrition, health and education’… It may not concern Mr Sharif unduly if the next generation of roads is as deserted as the last…[because] voters are impressed by gleaming new projects, even if they never use them. It’s an approach that has worked for Mr Sharif’s brother, Shehbaz, the popular Chief Minister of Punjab province. He has lavished resources on endless sequences of over- and underpasses to create ‘signal-free’ traffic corridors in Lahore, the provincial capital, that are of most benefit to the rich minority who can afford cars… There are limits, however. Khawaja Saad Rafique, the Railways Minister, recently admitted to Parliament that the country would not be getting a bullet train after all. ‘When we asked the Chinese about it, they laughed at us,’ he said.”

The Quetta Inquiry Commission Report

In the aftermath of the attack in Quetta on August 8, 2016, that wiped out an entire generation of senior lawyers in the province, a one-member inquiry commission, comprising (and led by) Justice Qazi Faez Isa, was set up by the Supreme Court. The commission submitted its report by mid-December of 2016, around the second anniversary of the APS attack.

Following is an excerpt of the commission’s report, which transcribes the commission’s interview with the Minister of Interior, Pakistan (See para. 10.5):

“Q41. Different publications state that two organizations, namely, Jamat-ul-Ahrar and Lashkare-Jhangvi Al-Aalmi are responsible for the attacks that took place on 8th October 2016, however these have not been proscribed by the Federal Government, why?

Ans. I do not have the answer for it.Q42. In your personal opinion should they be proscribed?

Ans. They should definitely be proscribed.Q45. The Government of Balochistan vide letter dated August 16th , 2016, wrote to you to ban the said two organizations, then why did you not do so?

Ans. NACTA has asked for the views and comments of the ISI and IB, however we are still awaiting their views.Q46. In other words, you have shelved the request of Government of Balochistan?

Ans. No.Q47. What is the purpose of soliciting the views of ISI and IB in this matter?

Ans. It is essential to consult the security agencies because they are the ones who know in great detail about the activities of such organizations and we would proscribe these organizations if they recommend so.Q48. I am mystified to learn that even when organizations have publicly proclaimed carrying out terrorist acts and after a lapse of eighty days, during which period there has been no retraction on their part, that you still have not proscribed these two organizations. Would you like to clear the mystification in my mind?

Ans. There is an unwritten process which the entire government knows, which is that organizations are proscribed once their credentials are verified and commented upon by the security agencies.Q49. Has the Ministry of Interior followed up on this matter?

Ans. I am not aware whether the Ministry of Interior has followed up on this matter.Q60. On the last date you gave your personal opinion stating that Jamat-ul-Ahrar and Lashkare-Jhangvi Al-Aalmi should definitely be proscribed, have they been proscribed to date?

Ans. Till this morning they have not been.Q61. Is the Ministry of Interior facilitating these organizations?

Ans. No.Q65. During the in-camera briefing by a Colonel working in the ISI the question with regard to proscription in respect of these two organization was asked and he had stated that proscription is the responsibility of the federal government and whilst the federal government may seek the opinion of ISI but if no opinion is rendered by the ISI it does not mean that the federal government should not proscribe an organization if it considers that it merits proscription. He further stated that he is not aware of the letter that had been written in this regard to ISI, however assuming that it was, the federal government should not wait indefinitely for ISI’s response and should do its job. Do you agree with what the representative of the ISI said?

Ans. Yes, I agree.Q66. Then why have these two organizations not been proscribed by the federal government?

Ans. This is some thing that NACTA has to do. Within the federal government there are different wings which are each supposed to carry out certain things and NACTA is the body which does this work ever since it has been formed and has been made functional. NACTA is one to do this and it is still waiting for certain responses to come their way to complete this.Q67. To state the obvious NACTA is not the Federal Government but is a statutory body set up under the National Counter Terrorism Authority Act 2013, however your answer seems to suggest that you do not know what constitutes the “federal government”, would you like to add any thing?

Ans. No.I want to state that during the break I was informed that NACTA has recommended for the proscription of Jamat-ul-Ahrar and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi Al-Aalmi and their recommendation has been received in the Ministry of Interior today. However, the decision in this regard has to be taken by the Minister for Interior.

Q94. Are you saying the decision to proscribe an organization falls within the domain and discretion of the Minister for Interior?

Ans. Yes.Q95. Under the Rules of Business of the Government of Pakistan would this be categorized as a policy decision?

Ans. Yes.Q96. Would it then be correct to state that these two organizations have not been proscribed because the Minister for Interior did not want to do so?

Ans. No, this would not be correct as no recommendations from NACTA in this regard had been received.Q97. Is it not amazing that organizations which claimed the responsibility of the attack that took place on August 8th, 2016, which was three months and six days ago, is only now being referred to the Minister for Interior to take a decision in this regard?

Ans. I would not categorize this as strange.”

The excerpt above, though self-explanatory, clearly shows the disconnect between not just different organs of the government, but also between the government and statutory bodies and the Minister and his own Ministry.

The report proceeds to inform the readers that the Minister of Interior held a meeting with the chief of three banned organizations (SSP, ASWJ and Millat-e-Islamia), Ahmed Ludhianvi, at Punjab House, in Islamabad’s Red Zone (See para. 10.11). Now there are two aspects that are essential to be looked at:

- As per the minutes of the singular meeting, NACTA has held (in 2014) (as per the Report – See 10.12),

- ‘Proscribed organisations not to be allowed to conduct public gatherings/meetings’; and

- ‘Action be taken against the office bearers and activist of such organizations’.

- In the reply submitted against this report, the counsel for the Minister of Interior states:

- “The list of participants was not conveyed [to Nisar] and the minister was not aware that Ludhianvi was part of that delegation,” he said, adding that the report gave an impression that the Minister accepted demands of the delegation and was socialising with outlawed outfits on a daily basis.

Now here’s the issue. Dealing with point number 2 first, there is a problem of striking magnitude staring readers in the face. Let’s put it into context. According to the counsel for the Minister – of Interior – the Minister was “not aware” of the composition of the meeting he was attending. Naturally, one would assume it may not have been vital for the Minister of Interior to know whether the leader of a proscribed organization formed part of the meeting the Minister was attending.

But let’s contrast this with the task of the Ministry of Interior, as per the very first point in the Rules of Business pertaining to the purpose of the Interior Division:

Internal security; matters relating to public security…

Let’s go back two steps. Referring to Q.49 from the reproduced transcript above, as merely a case study, one may see that the Minister for Interior was not even aware whether the Ministry under him had followed up on the matter or not – a matter of national security and human lives.

This leaves two possibilities: either the Minister does not enjoy the trust of the Ministry, or the Minister is too preoccupied with other issues to remain abreast of such matters – either of the two scenarios is equally worrisome.

Coming back to point number 1, the following is an excerpt from the inquiry commission’s report of a transcript of the commission’s interview with the Chief Secretary of Balochistan (See para. 10.11):

“Q23. In your experience what further steps can be taken to combat the menace of terrorism, extremism, hateful speeches and literature?

Ans. I would like to respond to the question in some detail. Firstly, I’ll attend to what can be done at the national level and what can be done at the provincial level. At the national level what is lacking is a national narrative and a counter-narrative to negate the extremist thought and propaganda of terrorist organizations and those indulging in hate speech and in failing to do so terrorism continues to breed. This is connected with the second problem which is that we cannot compartmentalize proscribed organizations or take efforts provincially alone. I can better illustrate this by giving an example; Balochistan does not permit… ASWJ… from holding any meeting or propagating its views but the efforts of the province stand defeated if the very same organization manages to hold a public demonstration at the Minar-e-Pakistan in Lahore or is permitted to become a member or part of a larger organization, i.e. Difa-e-Pakistan Council. This example is not a notional example but has happened recently.”

Here is another point of concern then: As under the Fourth Schedule of the Constitution of Pakistan, the security of Pakistan is an item on the Federal Legislative List, i.e. it remains with the federal government and does not (or, more aptly, should not) devolve (theoretically, at least) to the provinces. And yet, it would seem that this devolution is the case at hand.

Going beyond the issues with the federal government and the related statutory bodies, the report also highlights the blatant inadequacies of the NAP (See para. 13.1): “Though the [NAP] document is categorized as a ‘plan’ it does not have timelines for achieving any of the twenty goals that have been set. It does not stipulate who will be responsible for implementing its different components. It does not mention who will monitor progress or lack thereof, and in the case of failure to achieve compliance, the follow-up action to be taken and by whom.”

On the issue of the registration of madaris (plural of madrassa), the commission wrote to the five wifaqs (educational boards) of the madaris and their association, the Ittehad Tanzeem Madaris. The commission received responses from all the wifaqs and, despite a lack of centralized record by the government (wherein the Ministry of Religious Affairs has no such data and shifted the onus entirely upon the Ministry of Interior and NACTA), was able to ascertain that a total of 26,465 madaris were affiliated with them (See paras. 15.4 – 15.5).

In other words, the madaris in Pakistan are better organized than the government.

Let that sink in.

Oh. And there’s also this (See para. 33): “These were not the first attacks committed by these terrorists. If the functionaries of the state had established a bank of forensic information on past attacks, and pursued the cases, they may have prevented the attacks of August 8, 2016 …”

Where Now?

It is high time that we, as a people, as a nation and as a state, come together on the same side in this fight against militants, terrorists, terrorist organizations, militant non-state actors and proliferators of hatred, violence and incitement to the same.

Let’s put into perspective how resilient we have been: “Three terrorist attacks a day take place in Pakistan. There have been 17,503 terrorist attacks in Pakistan from January 1st, 2001, to October 17th, 2016…” (See para. 10.1 of the report).

Now, more than ever, we need to be sure that our resilience does not become our apathy.

Further, one can hope that the recommendations put forward by the Quetta Inquiry Commission in its report (See para. 34) are not brushed aside or ignored, and are both followed and implemented – from the development of a national counter-terrorism narrative, to the media reporting on such incidents responsibly, to the government, for lack of a better way to phrase this, pulling up its socks.

Statistics should not replace the priceless value of human lives. And our priorities should not be so easily swayed that we may forget the sheer decimation this menace has caused our fellow nationals – our fellow human beings.

This has to stop.

Please.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which he might be associated.