Family is the very foundation of society and the state is bound to protect the institution of marriage, the family, the mother and the child.[1] Unfortunately, according to the statistics on family matters pending before our judicial bodies, 128247 cases are awaiting disposal in the family courts of Sindh, out of which only 23860 have been decided.[2] In Punjab, 327533 cases await disposal in the family courts, out of which only 168407 have been addressed.[3] This is happening while the state is bound to provide inexpensive and expeditious justice to people.[4]

This article will attempt to discuss the judicial systems that exist in Pakistan, why some people prefer informal systems and the flaws that exist in the judicial system of Pakistan. This article will also attempt to determine the extent to which certain systems may be more practicable for the dispensation of justice and examine the measures that can be taken to improve the judicial system in Pakistan. This will be done through an analysis of a judgment delivered by the former Chief Justice, Mian Saqib Nisar on the jirga system.[5]

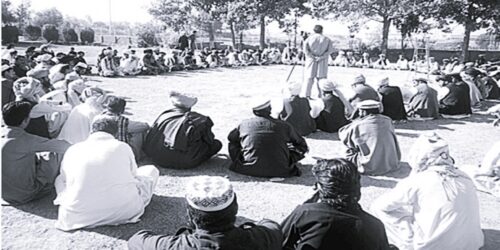

Pertaining to the verdict authored by Chief Justice (CJ) Saqib Nisar on the jirga system, when the National Commission on the Status of Women (NCSW) filed a petition to seek a declaration from the Supreme Court on the legality of the jirga system, the following key points were discussed:

- Bifurcated society

The statement of the CJ pointed out the following:

“Jirgas followed no precedent nor their decision subject to predictability or certainty, and personal knowledge and hearsay became tools for the determination of civil rights violations and criminal charges— Impending danger in allowing “societal customs” to override the law and jurisdiction of the “courts” was unacceptable in functioning democracy”.[6]

“…today, informal custom-driven parallel legal systems in the form of ‘Council of elders’ or ‘kangaroo courts’ exists in the tribal areas…”[7]

“Parallel adjudicating bodies in the form of Jirga/ panchayats etc., impinged upon the principle of separation of powers which was a vital feature of the Constitution [Art. 175(3) of the Constitution] — in the name of the preservation of Power Jirga/ Panchayats etc. assumed as the powers of a pillar of the state i.e., the “Judiciary”.”[8]

The terms “system based on societal customs” and “pillar of the state i.e. judiciary” represent two systems that exists in our society; one which does not run under constitutional and legal formalities and the other which does.

This indicates that our society is bifurcated because there are two kinds of people; those who avail ‘court facility’ to resolve their disputes and those who prefer the jirga system.

2. Jirga system in violation of Article 4, 10A, 25, read with Article 8

Article 4 – The right of individuals to be dealt with in accordance with the law. A jirga can interfere with the rights of citizens to enjoy equal protection of law, prevent a person from taking actions which are otherwise not prohibited by law and compel them to take certain actions which the law does not oblige them to do.[9]

Article 10A – The right to fair trial. The CJ pointed out reasons for why parallel courts were in violation of due process and fair trial in Shazia Bibi’s Case:

“38 – Within the Jirga system, no specific procedure is followed. It is the whim and choice of the Jirga People to adopt any procedure even if it is detrimental to any party. They are free to pass a verdict on the basis of personal knowledge or hearsay. It is noticed that in Jirgas, they only settle the disputes but do not implement justice in accordance with the law…”[10]

Article 25 – The equality of citizens. This right also gets flouted as the persons appearing before jirgas, etc. are not treated with equality during the so-called trial.[11]

Article 8 – Laws inconsistent with fundamental rights. Such laws shall be deemed void:

“…settling disputes is hit by Article 4,10A and 25 read with Article 8 of the Constitution which enjoins that no custom in derogation of any fundamental right can prevail under the law.”[12]

3. Jirgas may operate within the prescribed limits of law

As mentioned in para 5 of the same judgment,

“… there are certain customary and traditional sentiments attached to such terms and practices which do not necessarily involve the holding of parallel courts but instead entail a gathering of village elders to resolve a dispute which can within permissible limits of law be settled outside the court…”[13]

Therefore, it is crucial to clarify that jirgas may operate within the prescribed limits of the law, to the extent of civil and commercial disputes,[14] and only if the parties approach such dispute resolution systems voluntarily.[15]

4. Jirga decisions may fall under the following mechanisms:

- Arbitration;[16]

- Mediation (for civil disputes and minor offences);

- Negotiation; or

- Reconciliation (for family disputes).[17]

The guidance for law enforcement agencies to be vigilant and initiate investigation against both reported and unreported crimes[18] indicates that flaws exist in a state-owned judicial system which must be rectified through general public awareness campaigns in order to reform the existing executive, legislative and judicial systems and processes.

People in Pakistan tend to adopt the state’s court procedure because it possesses the “command of the sovereign backed by sanctions”[19] and the jirga system to get “cheap and speedy” justice. However, both dominant practices are repressive and oppressive to some extent. One is “denying” justice through “delayed” procedures and the other is “burying” justice through “hurried” procedures.

Therefore, it is the need of the hour to adopt a middle ground in the form of “institutionalization of the jirga system”[20] synonymous to alternative dispute resolution (ADR) practices. Such institutionalization may include the following recommendations:

- Mediation and communication skills development programs must be conducted to train citizens as well as raise awareness amongst them regarding the ADR system.

- Training programs must be ensured for people who usually play influential roles in society (especially in jirga hearings), including religious clerics who can be vital in shaping the mentality of our society.

- Records of problems and their solutions must be maintained.

- Approval must be made in accordance with the “general will”[21] of the people and must not be in violation of fundamental human rights.

In order to promote social peace and tranquility and safeguard the welfare of the fundamental unit (i.e. family) of society, matters must be resolved through a “peaceful settlement of disputes”. This is also compatible with the Muslim conception as Islam promotes mediation in the following words:

“If ye fear a breach between then twain, appoint (two) arbiters, one from his family and the other from hers; if they wish for Peace, Allah will cause their reconciliation. For Allah hath full knowledge, and is acquainted with all things.”

– Al Quran[22]

Having said that, the adoption of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms is not possible unless we initiate “behavioral change communication”[23] and “constructive dialogue”[24] amongst the public through proper platforms (such as the media, religious and cultural ceremonies, etc.). Otherwise, societal culture will take a long time to catch up with the ADR process and a cultural lag[25] will keep existing in our society.

References

[1] Article 35 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973

[2] Sindh High Court Report on: Statement showing Institution, Disposal and Balance of Main Cases and C.M.As/ M.As before the Court of Sindh, Principal Seat at Karachi during the month of December, 2019.

[3] Punjab High Court Report on: Statement showing Institution, Disposal and Balance of Main Cases and C.M.As/ M.As before the Court of Punjab, during the year of 2016

[4] Article 37 (d) of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973.

[5] PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218, National Commission on Status of Women through Chairperson and others VS. Government of Pakistan through Secretary Law and Justice and others. (C.P no. 24 of 2012 decided on 16th January, 2019)

[6] Para (b) Constitution of Pakistan, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[7] Para 1, Judgment; Constitution Petition No. 24 of 2012, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[8] ibid

[9] Para 13, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[10] Para 10, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[11] Para 13, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[12] Para 8, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[13] Para 5, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[14] Para 11, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218 “In judgement Shakti V. Union of India the Indian Supreme Court stated:–41- If there is offence committed by one because of some penal laws, that has to be decided as per law which is called determination of criminality. It does not recognize any space for informal institution for delivery of justice”

[15] Para 13 Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[16] Para 10, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[17] ibid

[18] Para 14, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218

[19] Austin Theory on Sovereignty; Jurisprudence by Imran Ahsan Khan Nyazee

[20] Para 20, Judgment; CJ Mian Saqib Nisar, PLD 2019 Supreme Court 218; (statement “..to ensure that the rule of law is observed by reducing jirga/ panchayat etc. to Arbitration Forums…”, indicating the institutionalization of jirga system.)

[21] Bentham Theory of Utilitarianism on General Will; Jurisprudence by Imran Ahsan Khan Nyazee

[22] Soorah Nisa Ayat no. 35, Al Quran

[23] SBCC for Emergency Preparedness Implementation I-Kit; what is Social and Behavior Change Communication?; http://sbccimplementation.org/sbcc-in-emergencies/learn-about-emergencies/what-is-social-and-behavior-change-communication/

[24] Constructive Dialogue Modelling (speech interaction and rational agents) by Kristiina Jokinen

[25] http://sociologydictionary.org/culture-lag/

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which she might be associated.