Unnatural Treatment of Male Rape by the Law: An Opportunity Missed

When Law and Society Reflect Each Other

This is not the first time this has happened and it will unlikely be the last.

With reports of recovery of the remains of three minor boys, displaying signs of sodomy,[i] from Kasur’s Chunian tehsil making headlines,[ii] it would be a painful but necessary reminder that this is not the first time that such heinous acts targeting minor victims (or male minor victims specifically) have been reported.

Back in August 2015, when the biggest child abuse scandal in our country’s history[iii] jolted the very same region of Kasur, a large number (out of over 280 victims that had been discovered) belonged to male minors. One would have imagined that the sheer magnitude of the offences discovered at that stage would have prompted the law to respond and remedy the mischief. And the law did respond.

Of course, whether the response actually remedied the mischief is an entirely different matter altogether. The case of Zainab Ansari in 2018 and the cases of Faizan, Ali and Suleman provide us with burning evidence to the contrary.

It is said that the law is generally understood to be a mirror of society — a reflection of its customs and morals — that functions to maintain social order. With cases of sexual abuse still rampant, particularly targeting male minor victims, it comes as no surprise that under the law of Pakistan, as it presently stands, the rape of a male individual, whether adult, minor or even disabled, is not taken very seriously as an offence.

Indeed, whilst the foregoing is a bold statement to make, the same is also easily verifiable from an appreciation of the relevant laws.

Under the law of Pakistan, as it presently stands:

- a man has not been recognized as a victim of “rape”;

- sexual intercourse with a man, adult, minor or even disabled, against his will or without his consent, is categorized as an “unnatural offence”, regardless of the gender of the transgressor;

- cases where both transgressor and victim are female also fall within the category of “unnatural offences” as opposed to “rape”, regardless of whether the victim is adult, minor or disabled; and

- the punishment for an “unnatural offence” is less severe than that provided for “rape”.

The Offence of “Rape”: Section 375 of the Code

The offence of “rape” has been defined under Section 375 of the Pakistan Penal Code, 1860 which provides the following:

“A man is said to commit rape who has sexual intercourse with a woman under circumstances falling under any of the five following descriptions:

(i) against her will.

(ii) without her consent

(iii) with her consent, when the consent has been obtained by putting her in fear of death or of hurt,

(iv) with her consent, when the man knows that he is not married to her and that the consent is given because she believes that the man is another person to whom she is or believes herself to be married; or

(v) with or without her consent when she is under sixteen years of age.

Explanation: Penetration is sufficient to constitute the sexual intercourse necessary to the offence of rape.”

As manifest from an appreciation of the opening words of the provision, the offence has been worded in a manner according to which only a “man” can “rape” a “woman”.

Such contention is strengthened when one views the opening words in the context that follows, namely, the five circumstances, satisfaction of any one of which would be sufficient to constitute the offence. This certainly lends credence to the first truth sought to be confirmed.

Since Section 10 of the Code uses the words “man” and “woman” to denote male and female beings “of any age”, the provision clearly covers the respective cases involving minor male transgressors and minor female victims as well.

So what about other cases such as the following?

- What about the case where the victim subjected to sexual intercourse against will or without consent is male, or worse, a minor or disabled male?

- What about the case where both transgressor and victim are female, or worse, the situation where the latter is a minor or disabled?

- What about the case where the victim subjected to sexual intercourse against will or without consent is male (adult, minor or disabled) and the transgressor female?

As is evident, one must look elsewhere for answers to such questions.

Section 377: The Residuary Cases

For such cases, one has to necessarily rely upon Section 377 of the Code which provides for “unnatural offences”:

“Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term which shall not be less than two years nor more than ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.

Explanation: Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this section.”

A perusal of Section 377 leads to the invariable conclusion that this particular offence has been worded in a manner so as to make the gender of the transgressor irrelevant. The word “whoever” is irresistible evidence in such regard. The “will” or “consent” of the victim is also an irrelevant consideration, unlike Section 375 which recognizes them both as two of the five elements, satisfaction of any of which is necessary to constitute the offence of “rape”.

Similarly, the crime identifies three categories of victims: men, women and animals. Here too, no distinction has been made between the binary genders; both have been recognized as equal victims (along with animals, naturally).

Interestingly (if not also quite lamentably), this is in stark contrast to Section 375, the provision dealing with rape, which only recognizes the male-transgressor-on-female-victim paradigm.

Naturally, considering the expansive nature of Section 377, it is easy to see how (and why) cases involving sexual intercourse with a man (adult, minor or disabled) against will or without consent (literally “male rape”) fall within its purview, or for that matter cases where both transgressor and victim are female, regardless of age or disability.

This lends credence to our second and third noted truths.

A Case of Different Degrees of Reprobation

To highlight more differences between the two provisions (and to progress to the fourth truth):

Section 377 provides either “imprisonment for life” or “imprisonment of either description for a term which shall not be less than two years nor more than ten years” along with fine, as possible punishments.

On the other hand, the punishment provided for “rape” (in Section 376 of the Code) is far graver, namely, “death” or “imprisonment of either description for a term which shall not be less than ten years or more than twenty-five years” along with fine.

While such observations ought to be sufficient for the purpose of establishing the fourth truth, it may be beneficial to also note that where the offence of “rape” has been committed by two or more “persons”, in furtherance of common intention of all, the punishment prescribed is “death” or “imprisonment for life” (Section 376(2)). Naturally, since Section 375 in defining “rape” restricts itself to the “male” transgressor only, the word “persons” as utilized in Section 376(2) is illusory at best.

Viewed in the appropriate context of Section 375, the term “persons” as used in Section 376(2) necessarily means “men”.

There is yet another important aspect in this matter. According to Section 376(3) of the Code (as inserted by Section 5(b) of the Criminal Law (Amendment) (Offences Relating to Rape) Act 2016):

“Whoever commits rape of a minor or a person with mental or physical disability, shall be punished with death or imprisonment for life and fine.”

Here too, context necessitates that the word “whoever” be interpreted as necessarily restricted to the male offender.

So too, regrettably, must the word “minor” be necessarily interpreted as limited to the female minor victim. After all, the definition of rape as provided in Section 375 remains restricted to the male-transgressor-on-female-victim paradigm.

The Mischief

This is problematic for various reasons and an analysis of the constitutional objections one may have to this situation would be so expansive that it may be better served by a separate inquiry.

It seems unlikely that the intention of Parliament in introducing the 2016 amendment to provide for a legal situation where non-consensual sexual intercourse with a minor or disabled male was to be treated as less serious of an offence (since the punishment it carries is less grave) than non-consensual sexual intercourse with a minor or disabled female. As noted by history, most victims of the 2015 scandal had been male minors and the law’s response to remedy such evident mischief might as well have been no response at all.

Moreover, victims recognized in all four categories are equally vulnerable based on their “age” and “disability” as opposed to their respective genders.

It is further unlikely for Parliament to intend to show leniency towards transgressors who victimize minors (or the disabled) based on the gender of the offender. The gender of the transgressor does not determine the degree of harm caused, particularly when the victim is part of a vulnerable class.

Be it inadvertence or legislative policy, the situation is what it is.

The law seems to condemn those who target male minors “a little less” than those who target female minors. The law seems to condemn those who target males with a mental or physical disability “a little less” than those who target females with the same disabilities. The law even seems to condemn females who target other females (whether adult, minor or disabled) “a little less” than males who do the same.

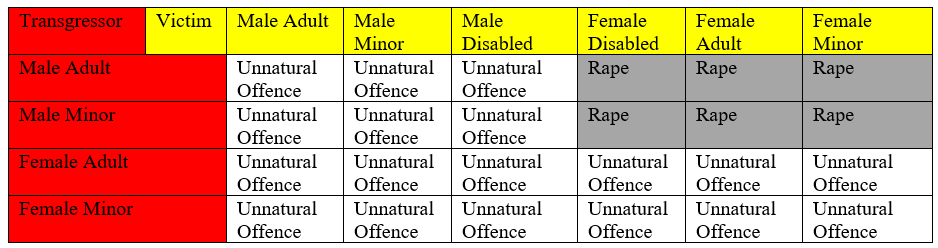

In poker terms, “gender” trumps “age” and “disability” and the following table seems to illustrates this:

The Irony

There is, quite fascinatingly, an irony to this which has perhaps dawned upon those with a deeper appreciation of the historical context of Section 377.

The said provision (which makes consent an irrelevant factor) has also been the primary provision responsible for criminalizing homosexual intercourse.

It is, of course, ironic that the same provision, when viewed in conjunction with Sections 375 and 376, provides for a legal situation where, when it comes to non-consensual intercourse, the “homosexual” type is the lesser condemnable one.

———-

References

[i] https://www.dawn.com/news/1505906

[ii] https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2019/09/17/kasur-still-hub-of-child-abuse-two-years-after-notorious-zainab-rape-case/

[iii] https://nation.com.pk/08-Aug-2015/country-s-biggest-child-abuse-scandal-jolts-punjab

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which he might be associated.