Bail is granted as a matter of right in bailable offences, however, once arrested in a general non-bailable offence, the accused has to bring his or her case within the ambit of the colonial language in section 497(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) 1898 to regain his or her liberty. The section reads as follows:

“…there are not reasonable grounds for believing that the accused has committed a non bailable offence, but there are sufficient grounds for further inquiry into his guilt…”

Similarly, the remedy of bail-before-arrest, an equitable and extraordinary relief, can by sought by an accused from the court in a non-bailable offence by successfully establishing mala fide intent on part of the prosecution.

In order to seek bail, the burden lies on the accused to approach the court. The court tentatively assesses the facts, circumstances and merits of the case in applications for bail before and after arrest. Grounds such as remote chances of tampering with evidence, no risk of absconding, ties of the accused person with the society and completion of investigation are often brushed aside for being inferior to the actual merits and strength of the case.

Interestingly, the Supreme Court has been demonstrating polarity while deciding on bail-before-arrest applications. The Supreme Court, in various bail matters, has declined to grant judicial protection from arrest for the reason that extraordinary relief cannot be extended in every run-of-the-mill case apparently founded upon incriminatory evidence. On the other hand, the Supreme Court has, on certain occasions, extended the relief of judicial protection from arbitrary arrest based on the principle of the court being the torchbearer of fundamental rights concerning an individual (such as the right to fair trial, liberty and dignity).

The threshold of “tentative assessment” of the merits of a case in a bail application also varies from court to court. The courts, on numerous occasions, have refused bail by ruling out the argument and plea of alibi at the bail stage and holding it to be a “deeper assessment of fact…to be the domain of trial court”. On the other hand, the Supreme Court in a particular case, while reversing the bail refusal order of the High Court, did delve into the examination of a confessional statement of a co-accused implicating the bail applicant and held such exercise of scrutiny to be within the ambit of ‘tentative assessment’.

Arbitrary or unnecessary arrests and the failure of police to exercise the power to grant bail in a non-bailable offence (permitted to them by law under s. 497 CrPC) have put citizens in a state of insecurity. The longer incarceration of high profile politicians belonging to the Opposition benches, without conviction (especially during the last 3 years), testifies to the fact that bail law has become redundant. The state of affairs pertaining to the poor and the weak behind bars may be even more discouraging.

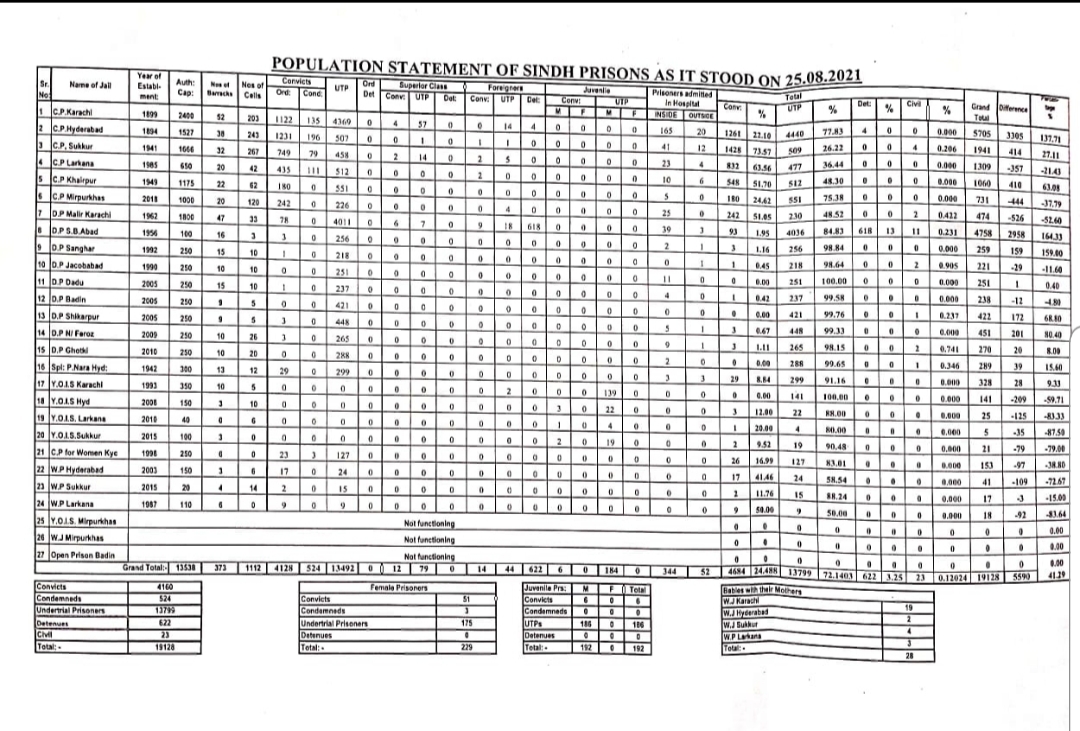

According to a joint report by the London-based Amnesty International and Justice Project Pakistan released in December 2020, prisons all over the country had around 78,000 inmates against the official capacity of 58,000. The under-trial prisoners (UTPs) for want of bail were 65% of that population. As of 25th August, 2021, the Malir Karachi prison housed around 4,800 prisoners against the authorized capacity of 1,800. The percentage of UTPs stood at a daunting 85%. The single-jail cell built for a maximum of 3 inmates housed 6 to 15 persons. Conversely, as per the data available on Prisonstudies.org in March 2021, prisons in the UK (England and Wales) only had around 16% UTPs out of the total number of prisoners.

Based on the aforementioned facts and figures, the need of the hour is to depart from the colonial law of bail envisaged under section 497 of CrPC and introduce modern legislation similar to the UK’s Bail Act of 1976. Moreover, grounds of mala fide intent and tentative assessment of the merits of the prosecution’s case should be given secondary consideration. The onus should be on the prosecution to dispel the statutory presumption of grant of bail to an accused by invoking statutory exceptions such as there being substantial grounds (which are nothing less than ‘real risk’) for believing that the accused would fail to surrender, commit an offence while being out on bail, interfere with witnesses, or obstruct the course of justice. The court should also be guided by statutory factors such as the character and antecedents of the accused, any previous record of bail of the accused, the strength of the evidence, the nature and seriousness of the offence and the probable method of dealing with the offender in question.

The conditions on which an accused may be granted bail can also be given statutory footing. They may include making residence a condition, reporting to a police station, subjecting to a curfew, restricting entry into a specified area, restricting contact with a certain person, subjecting to electronic tagging, depositing of security, etc. If such conditions cannot dispel real risk, only then should the accused be remanded into custody.

Police officers should also be encouraged by the executive and the judiciary to exercise their power to grant bail in non-bailable offences. In doing so, the police officers should be under a duty to write down the reasons for grant of bail, as envisaged in Rule 26.21(5) of Police Rules 1934. The same must be made mandatory while refusing bail in non-bailable offences. Such reasons should be appended every time an officer seeks custody from a judicial magistrate for investigation purposes and at the time of submission of the final investigation report.

In a recent judgment of the honourable Supreme Court, authored by Justice Mansoor Ali Shah, it has been held that while considering bail petitions in National Accountability Bureau (NAB) cases under Article 199 of the Constitution, the High Court should consider constitutional grounds to enforce any of the fundamental rights of the accused, as opposed to the narrow grounds of s.497 CrPC. Moreover, in contrast to the requirement of s.497 CrPC, the Supreme Court has further held that it should be for the prosecution to show that it has reasonable grounds to believe that the accused has committed an offence. One wonders if the grant of bail has been now made easier than in otherwise general criminal cases falling under the scrutiny of the colonial language of s.497 CrPC. However, this development is akin to a drop in the ocean and much more is needed to be done by the legislature.

The saddening part in all of this is that criminal law does not provide for compensation to the acquitted persons who had been incarcerated earlier for a certain period during trial. Unfortunately, the intense political discord between legislators across the aisles in Parliament signifies that criminal justice reforms are nowhere in sight.

References

https://www.prisonstudies.org/country/united-kingdom-england-wales

https://apnews.com/article/pakistan-prisons-islamabad-coronavirus-pandemic-prison-overcrowding-47cd61d890b4a6d613cdd461f71e3686

https://tribune.com.pk/story/2183601/1-pakistani-prisons-house-77275-inmates-authorised-capacity-57742

https://tribune.com.pk/story/2300230/supreme-court-divided-on-question-of-pre-arrest-bail

https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/865967-new-police-rule-amendments-meant-to-ensure-no-unreasonable-arrests

https://www.dawn.com/news/1650193/supreme-court-rules-against-arrest-without-incriminating-evidence

https://www.google.com/amp/s/tribune.com.pk/story/2321297/onus-on-nab-to-show-reasonable-grounds-to-deny-bail%3famp=1

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any other organization with which he might be associated.

Indeed a mind-alerting piece from the learned counsel. It’s need of the time that rectifying steps should be taken as soon as possible.