A few days ago, results of the 2019 Central Superior Services (CSS) competitive exams were announced by the Federal Public Service Commission (FPSC). Much is lamented every year about about the exam’s consistently low passing percentage of 2.5% and the crippling inadequacy of the education system in Pakistan. However, this year is marked by some peculiarly contentious observations.

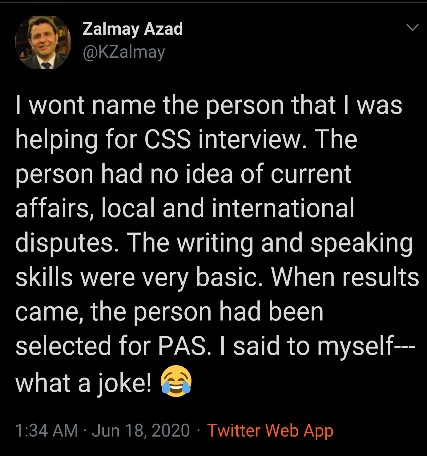

For starters, some exceptionally bright candidates did not get allocated. If being a foreign graduate or having a Shakespearean command of English are your suspected areas of shortcoming, then hold thy verdict, many enviable among mankind have failed. Some of most the acclaimed mentors themselves, who had been the expected toppers of the year, failed. On the other hand, some average, run-of-the-mill candidates seemed to have secured top allocations. A tweet by Zalmay Azad has been trending on social media in this regard:

“I won’t name the person that I was helping for CSS interview. The person had no idea of current affairs, local and international disputes. The writing and speaking skills were very basic. When results came, the person had been selected for PAS. I said to myself—what a joke!”

What could have gone wrong? An answer which is commonly sold on the streets, even by those not remotely associated with the exam, is that “CSS is a lot about your luck”. An exceedingly capable candidate himself said in a video, “You need three things for CSS; knowledge, analytical capability and luck. The former two you can get with hard work. The latter, I think I lacked that.”

As a realist, doctor and student of science, I find it difficult to apprehend this ‘third’ factor. It is true that as Muslims, taqdeer (fate) is one of the basic tenets of our faith, and I find it rather beautiful that even the most commendable youngsters can smile at their own failures just because they trust Allah to be the best of planners. However, as a follower of the same religion, I urge our youth to have a stronger belief in the scriptures where Allah encourages hard work (Al-Quran 53:39).

As an analyst, I find it extremely counterproductive to attribute everything to luck and not hold the relevant authorities accountable. It is downright ridiculous to stifle management flaws during a pandemic by labeling the situation as Allah ka azaab (calamity sent by God), or glorifying the plane-crash victims of a hemorrhaging state-owned enterprise as shaheeds (martyrs), absolving those in charge of any liability. The same goes for the most coveted exam in this country. Bobbing our heads at the “luck factor” entails no wisdom. If you expect the bureaucracy of this country to be selected by some sort of sorcery, you should certainly expect them to run the country with sorcery as well. Statements alluding to the supernatural in trying to cover naked governance flaws should come as no surprise then.

Selling ‘luck’ as the greater driving force for allocations is yet another way of hiding the fact that something is seriously flawed with the FPSC’s exam checking process. It is true that the exam is tough and the journey is rigorous, but making it ‘tougher’ will not solve the problem. Some standards need to be set for the examiners who have been put in charge of approving the builders of the nation. Much of the guidance offered by exam preparation centres alludes to speculations on the “wishlist of an examiner”, overemphasizing on presentation and obsolete flowery techniques and paying no heed to a candidate’s own unique perspective and analysis. Despite the whole ordeal of exam prep and submission, the outcome is mostly dependent on the whims and moods of that one stranger who gets hold of your paper. That, we can call, the “luck factor”.

The Commission needs to set its priorities straight. Times like the present are indeed lucky when so many young people from highly qualified local and international varsities are pouring in clusters, sacrificing their otherwise illustrious careers and working arduously to secure well-deserved positions for themselves so that they can actually contribute to improving the system instead of bickering about it on social media. Letting these youths down after an incessantly long period of two years on account of some paranormal forces will only drive them away from this country. Complaining about brain-drain will then no longer be justified.

Adding to the humour and conspiracy surrounding the exam and recently making rounds on the internet were pictures and interviews of exam toppers claiming affiliations and pouring gratitude for their coaching institutes. Keeping conspiracies aside, some newly allocated officers seemed to speak with a genuine sense of association that cannot be feigned for the sake of publicity. However, the situation is more alarming than humorous.

A short disclaimer here: joining a tuition centre for preparatory help calls for zero criticism. Some institutes do a great job in shaping young minds and providing a platform to rub shoulders with like-minded intellectuals. They also provide an economic opportunity to bureaucrats who mean to impart sincere knowledge and earn a halal income post office hours. If anything, the academies have helped raise the standard and competitiveness of the successive generations of aspiring youths.

But this comes with a caveat. With so many youngsters looking up to the toppers, most may not be able to afford even a single academy let alone a jumble of those spelt out by the high achievers. On a holistic level, too many cooks can spoil the broth. Less is sometimes more and all that ‘branding’ may be sending very wrong messages to youngsters. All in all, the CSS exam which used to be known for its transparent recruitment procedure and accessibility to the middle-class is morphing into an elitist form.

The CSS exam per se is not attractive. No young man or woman would like to put his or her professional degree aside and begin studying a whole new set of subjects alien to him or her, that too against proportionately risky prospects of success. Success in the exam is vied for the sole reason that the very government which has been elected on its promise of providing jobs and human dignity has robbed our youth of both. The only vacancies ever announced in the country tend to get filled on the basis of naked, grotesque nepotism. In such times of debauchery, the civil service remains a hope, not only for the ridiculed, jobless professionals, but also for the rest of the nation.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of CourtingTheLaw.com or any organization with which she might be associated.